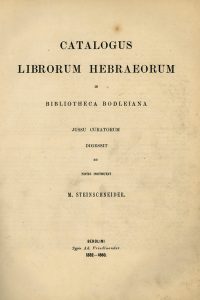

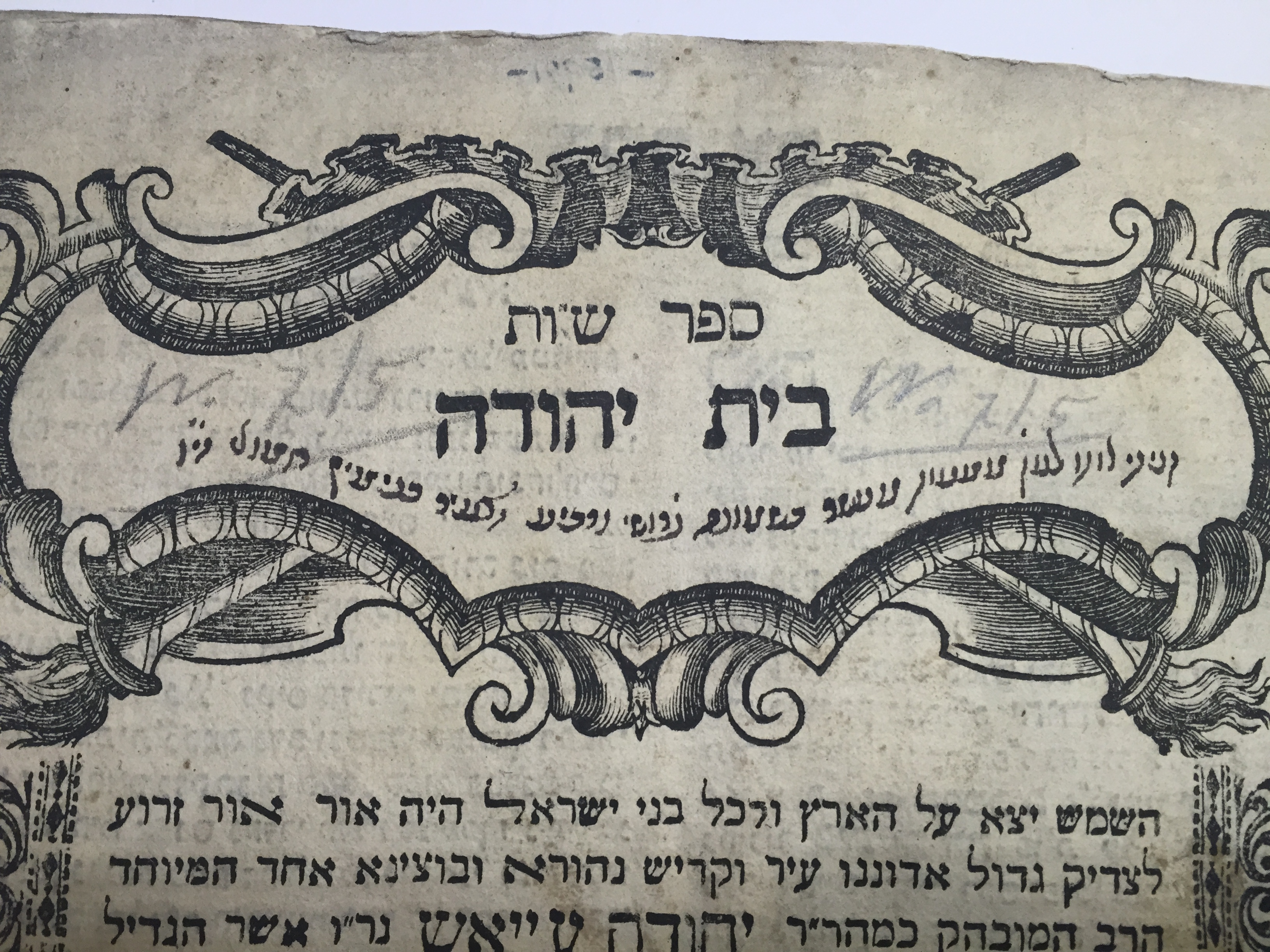

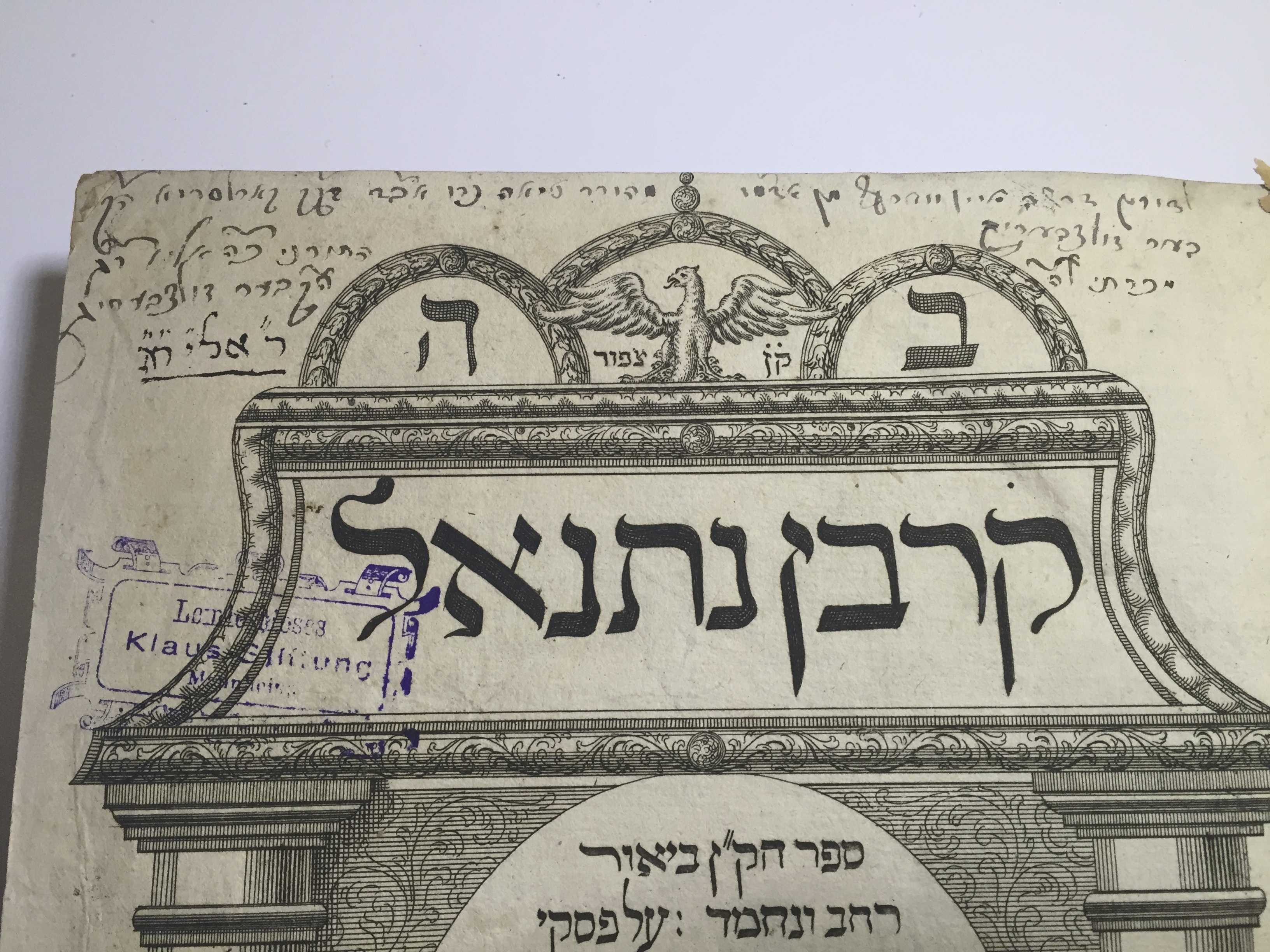

When I first began my research into the Oppenheim library, a senior scholar in the field casually suggested that I might also produce a new catalog of the collection. The Oppenheim library is a marvel of Jewish bibliography: it holds medieval scientific manuscripts, Yiddish pamphlets from Amsterdam, Sephardic and Ashkenazic Talmudic commentaries, calendars, broadsides, and mystical manuals, polemics alongside concordances, grammars, dictionaries, and glossaries. The last time a comprehensive catalog of the printed collection was produced was in 1929, in A.E. Cowley’s A concise catalogue of the Hebrew printed books in the Bodleian Library (Clarendon Press). Cowley’s work was based upon the painstaking labor of Mortiz Steinschneider’s Catalogus librorum hebraeorum in Bibliotheca Bodleiana (1852-60).

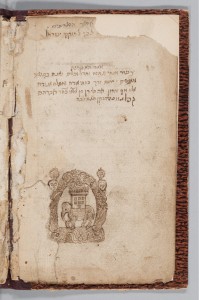

The Oppenheim collection has not had a shortage of catalogs. It began as a personal library, and its owner carried his own handwritten inventory of the collection with him wherever he traveled. He could consult it when he visited the great book markets in Leipzig to ensure that no new or old book escaped his great net. This notebook was also sort of “portable” library. It represented the sum total of the books he owned, and by extension, of the knowledge that he singularly possessed.

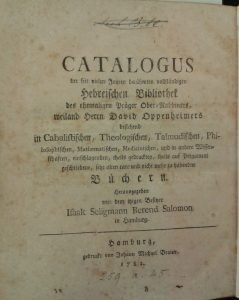

While the library was of great renown and under much demand in Oppenheim’s lifetime, after his death the historical winds of change began to blow in new directions. With the declining wealth of Oppenheim’s heirs, the library was prepared up for auction. The intellectuals of Central Europe oriented their knowledge pursuits in new directions: in the critical and focused library of the haskalah, in the culture wars between modernizers and traditionalists, in the fermentation and upheaval of the emergent Hasidic circles in the Polish-Lithuanian commonwealth. An auction of the collection in Hanover in 1782 found no buyer, but it did occasion the creation of a catalog. Another forty years lapsed before another auction yielded yet another catalog in Hamburg in 1826. And in the decades after the collection was purchased by the Bodleian Library of the University of Oxford in 1829, Steinschneider got to work on his magisterial Catalogus librorum hebraeorum.

So why would there be need for another inventory of this collection? My research brought me into contact with a myriad of byways leading from my central avenue into paths that could tell an infinite number of new tales. Every scholar who works in archives inevitably discovers so much more data than she or he will ultimately include in the final product. Leaving this data behind is a struggle and a shame, even if it is an occupational necessity. It can sometimes even be crippling for a published work. We’ve all encountered studies that derive from meticulous expert research, and then sag beneath the weight of the details. Some of us might recognize the hardship we face in submitting a piece of writing for publication when it means slashing away at so many hard-won bits of data.

Footprints, on the other hand, gives life to that data. It offers a venue other than the individual monograph or article for these triumphs of archival discovery to stay alive, and in the process become useful to others. Rather than pruning away material that will then never see the light of day, Footprints allows a scholar to publish that data by different means, and to receive credit for the act of scholarly research even when it does not eventuate in the footnotes of a monograph.

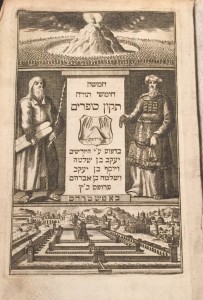

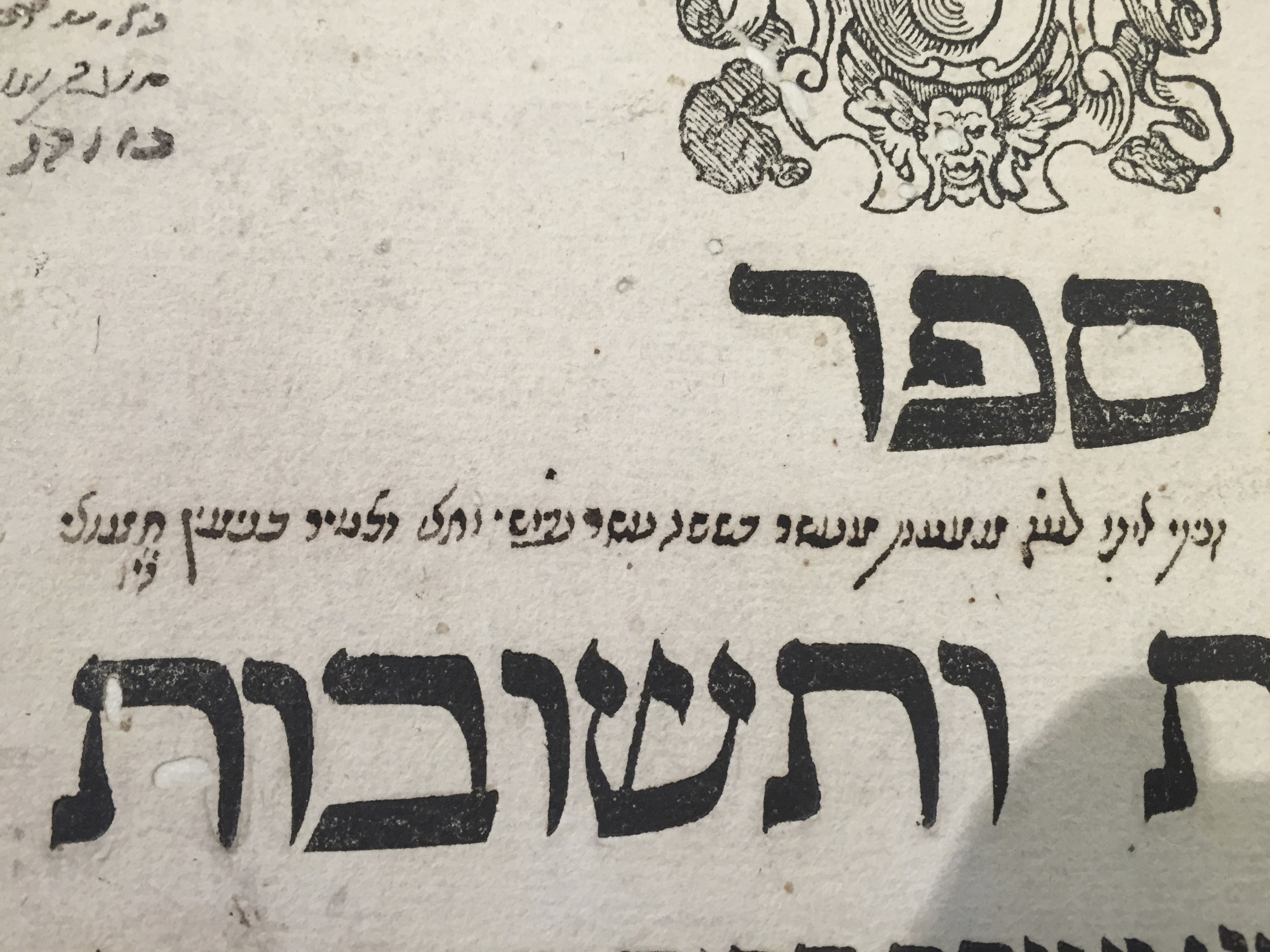

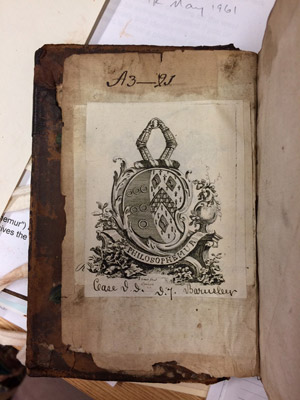

The beneficiaries of these micro-publications are manifold, especially in generating better inventories for the next user. For example, an extant copy from Oppenheim’s library (Sefer Mateh Aharon, Frankfurt am Main, 1678–Opp. 4o 1344) does not reveal much about itself. But when put into conversation with his personal, handwritten, catalog from the 1680s, we can learn that a book was owned and sold by a widow who was in need of funds, was bought by a wealthy young man whose father was a pillar of the Worms community, was stored in Hanover in the estate of the Court Jews to the man who would become King George I of England, and was lent to a young student, who returned it before it became a permanent fixture of a formal library. You can check out the complete footprint record here.

Ms. Opp. 699, f. 81v. (personal catalog of David Oppenheim of Prague), held by the Bodleian Library.

Who cares? The librarian, producing copy specific notes about a book that doesn’t tell its own story, who may not have the time or even the familiarity with these other documents that reveal hidden paths. The scholar of George I’s Court Jew. A historian of borrowing and lending practices. A graduate student who wants to know more about the economic position of widows and women in premodern society. This is the perfect space for librarians to both grow their individual catalogs and lend their material to the scholarship of others, and conversely for scholars to deposit the material they “just can’t fit” into a book or article for the benefit of the librarian and the next scholar to come along, all the while receiving credit for it.

Ultimately, such micro-research is a fun and fulfilling way to make new knowledge out of old data, and to contribute to an enterprise of growing information. In the words of my colleague Adam Shear, it ensures “no datum left behind.” For an example, stay tuned for my next post (called “In a Bind”).

Joshua Teplitsky (Stony Brook University) is one the of co-directors of the Footprints project. He is finishing a monograph about the library of David Oppenheim of Prague (1664-1736) entitled Collecting as Power: David Oppenheim, Jewish Politics, and the Social Life of Books in Early Modern Europe.

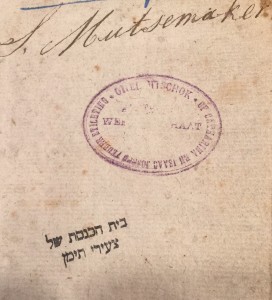

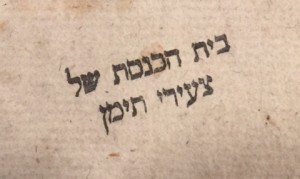

The third footprint was a stamp in purple ink indicating that the book had been owned by

The third footprint was a stamp in purple ink indicating that the book had been owned by

Recent Comments