Editor’s note: Chaim Meiselman is one of our most active contributors to Footprints, adding data from his own collection as well as from others, and he has assisted in identifying many of the difficult hands from the “can you help?” footprints. He reads a plethora of languages, including German, French, Latin, Hebrew, Yiddish, as well as Dutch, Polish, and Italian. Meiselman writes below about some items in his personal collection that are documented in Footprints.

Over the course of book collecting, I have begun entering data and inscriptions from my library into the Footprints Project.

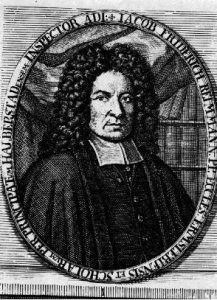

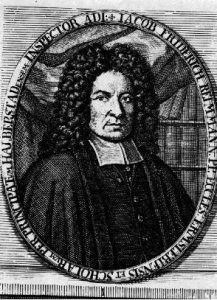

Jacob Friedrich Reimmann

I hope to share some of the Footprints in this space occasionally. I will begin this endeavor with some Latin and Greek sourced items from my collections.

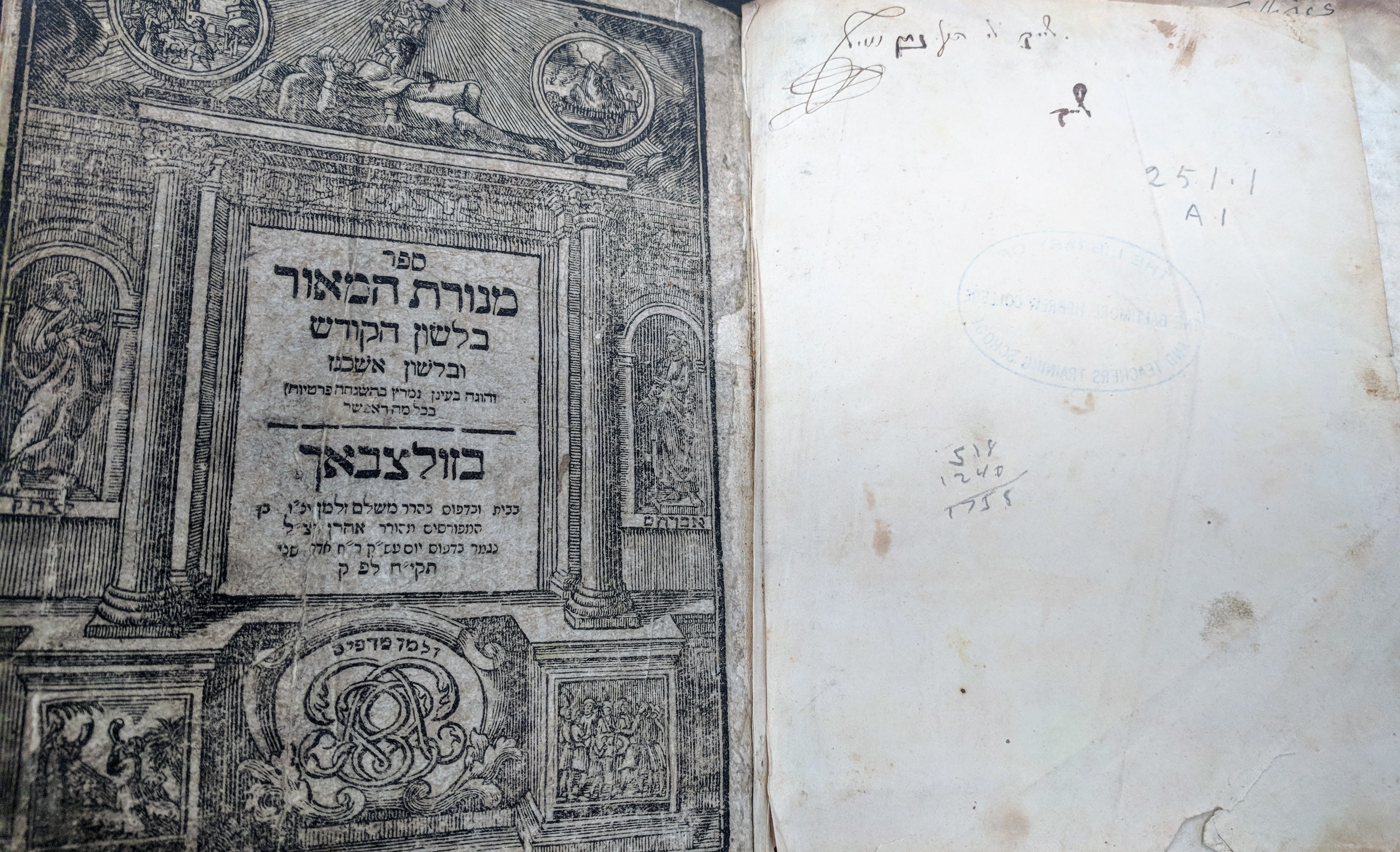

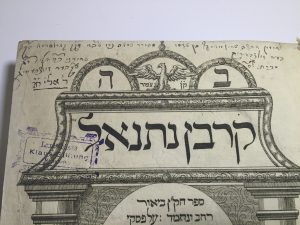

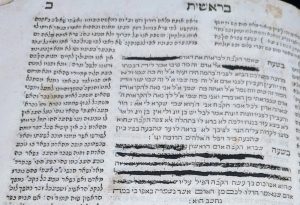

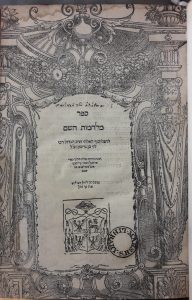

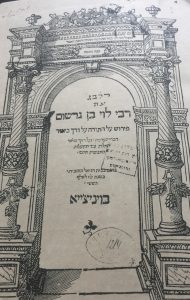

Liber Cosri (Kuzari): Basel, 1660

I will begin with a long inscription with a traceable owner. Jacob Friedrich Reimmann (1668 – 1743) of Hildesheim, was a Lutheran Theologian and historian. Included in his works are philosophy (and history of Philosophy), German religious poetry, and even a history of atheism.

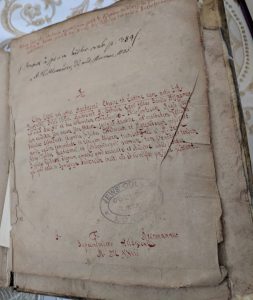

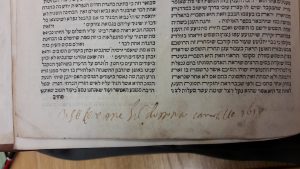

In my volume of ‘Liber Cosri’, the edition printed by Johann Buxtorf in Basel in 1660, Reimmann wrote a long description of the volume, and even compliments Buxtorf in Greek (perhaps a sign of fellowship among men of letters). In my Footprints entry on this inscription, I transcribed the entire inscription.

Here it is, beginning with my introduction:

Below I will transcribe the entire Latin inscription, because it is historically valuable. Reimmann was a friend (or peer) of Gotthold Wilhelm Leibnitz, Christian Wolff, Gottlieb Stolle and included in his correspondence Pierre Bayle, Johann Franz Buddeus, and other contemporary scholars.

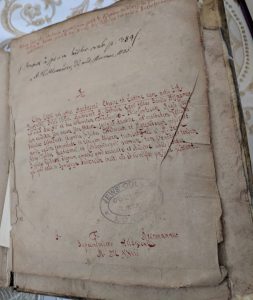

Inscription

“Liber Cosri vel potius Hachosari Ebraice et Latine cum notis Buxt. – Buxtorfii Basel 1660. Auctor est R. Jehuda Levi filius Saulis Hispanus – qui vixit Sec. (Saeculum) XII et huc colloquim Theologicum – Philisophicum. Regis Coser cum eruditis, Sive verum Sive dictum. scrip sit Arabice, et veritatem religionis Judaica defenderet, et contra insultus Ethnicorum et Karaitanum, vindicaret unde eadem tempentate in unquam obruam translatius R. Jehuda Aben Tybbon. Feranatensi, et Cohanstantinnopli primum ,tum Venetiis et tandem Basilea editum dignum omnino quod accurate et studiose abii lectitetur. qui quid satis in Synagoga Judaorium insit, ωζ ξν ςυγομπ mens picere gestiunt.

J. F. Reimannus

Superintendens Hildesiensis

M.DCC.XXiii”

Translation: Book (called) Cosri or better, Hachosari [printed] Hebrew and Latin, with [editions] addition of Buxt. – Buxtorf [;] Basel 1660. Authored by Judah b. Saul halevi in Spain – who lived c. 12th century among the theological and philosophical [scholarly] colloquium there. King Coser, the learned and erudite.. Written in Arabic as [for use of] true Judaic religious defense against the attacks of the foreigners and from within by the Karaites; R. Judah Aben Tybbon’s [translation] was not understandable to other translation. [Printed first in] Feranatensi [Fano], and Cohanstantinnopli [Constantinople] for the first time, next Venice, and I am most satisfied now with the studious and dignified one latest at Basil was published. The one who is able to satisfiy with Synagoga Judaicum is in here [i.e. the translator and commentor], ωζ ξν ςυγομπ (and more so, Greek) he has studied [looked at – lit.] carefully their time.

J. F. Reimann

Superintendant – Hildesheim

M.DCC.XXIII

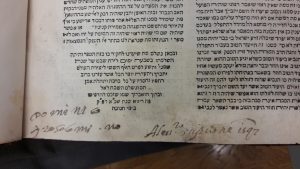

This volume was also in the collection of another Lutheran Theologian, Johann Hilpert (1627-1680) in Coburg. This is the inscription:

“Liber Cosri inter Christianus esse rari stium verbit J. Hilpertur un disquis. de mutuam itus e.s.p.d. scribet et.al. hic Hilpertus A.C. 1696 quo tem pocc a Buxtorfi nondum erat editas.”

Hilpertus is likely speaking of Johann Hilpert (1627-1680) , a Lutheran theologian from Coburg. Since he was dead at the date of this writing likely the note is of an inventory of his theological books.

Finally, this volume met a censor later in the 18th century. Here is the information:

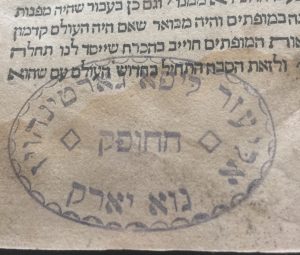

Text from inscription: L. Purarx in speciam hic sor nab. p. 384 .

Post script: In preparing this post for publication, Footprints co-director Michelle Chesner realized that there may yet be another footprint to be identified, based on the stamp from the Jews’ College Library in the image above. Chesner knew that there had been sales of books from Jews College Library at Kestenbaum and Co. in the early 2000s, and she checked her backfile of Kestenbaum catalogs (which Chaim Meiselman did not have) to see if it appeared there. Sure enough, this book (confirmed by the description of the binding) was Lot 115 in Kestenbaum Sale 23, March 2004. This is just another example of how allowing multiple people to access the same data can allow for much more “value added” in the long run.

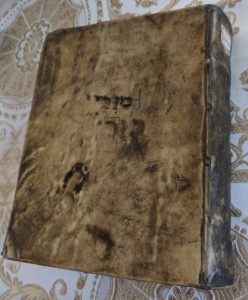

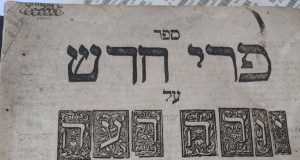

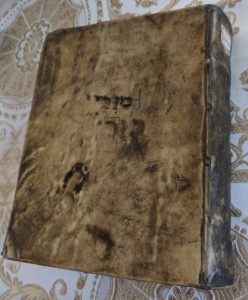

Book 2: Yalkut Shim’oni, Livorno 1649-50

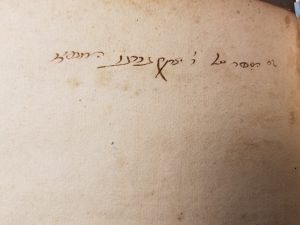

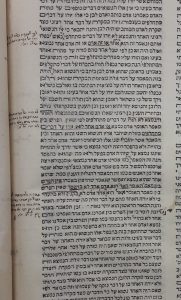

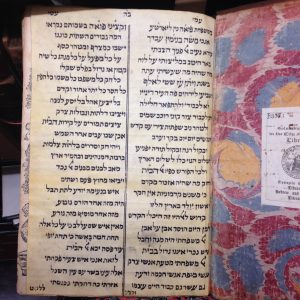

Contrast the previous detailed inscriptions with a copy of the large tome Yalkut Shimoni, published in 1649-50 in Livorno. My copy is without complete inscriptions or more traditional Footprints. However, it is clearly ex-library, and a fine copy; so I looked deeper.

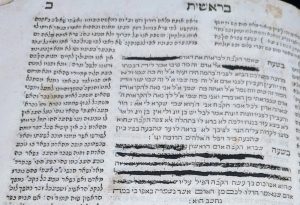

Censorship

The book is censored only for the beginning chapter of Genesis. That already gave me a clue that it wasn’t a traditional case of censorship; likely it was an aspect of ownership in the volume.

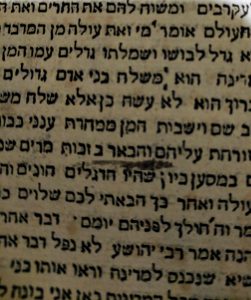

On close inspection, I found something very minute but telling.

On the opening chapter of Numbers, the text reads from the Midrash on the Well of Miriam. Thematically, the Midrash recounts that sustenance ended at the death of Moses, Aaron, and Miriam.

… והבאר בזכות מרים – והיכן היו עשויה כמין סלע/ the well, in the merit of Miriam, was composed ‘like a rock-form’.

Ascon

The interpretation of this passage differs; as an example, Rashi writes that it was rock-hard, and it would roll along as the nation traveled.

Between the lines of my copy, this volume was inscribed with one word: ‘Ascon’. This is a Greco-Latin word directly referring to natural sponge-material; the meaning being that the owner interpreted it as not being a rock at all, but a natural absorbent (which was used to give off and store water in the desert).

No other inscriptions are on the entire volume.

Recent Comments