Haim Gottschalk is a Hebraica and Judaica cataloger at the Library of Congress, currently working on the LC’s collection of Hebrew incunabula. He is also entering provenance data for the incunabula into Footprints. The views in this blog post are not representative of the Library of Congress or its staff.

In June of 2013, the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), which bills itself as the “definitive record of the English language”, added the word “Crowdsourcing” to its lexicon. The OED defined the word as “the practice of obtaining information or services by soliciting input from a large number of people, typically via the internet and often without offering compensation.” The word itself was coined by Jeff Howe of Wired Magazine by compounding two nouns – “crowd” and “sourcing”. The word was popularized in the title of his 2006 article “The Rise of Crowdsourcing.” “Crowdsourcing” is seen as a derivative of the word “outsourcing” (“Evolution of Crowdsourcing: Potential Data Protection, Privacy and Security Concerns under the New Media Age” by Buddlehadeb Halder. In Democracia Digital e Governo Eletrônico, Florianópolis, no. 10, p. 377-393, 2014. P. 378-379).

Although the word itself might be new, the concept is not. The key concept is the tapping into “a large crowd of people” for input. One of the earliest examples of tapping into a large crowd of people was the 1714 contest by the British government who was looking for a way of calculating a ship’s longitude. Over the centuries other projects similarly involved crowd-sourcing. In 2001 Wikipedia was launched, where information could be (and still is) added and updated by many people. In 2020, one can argue that the pursuit of a COVID-19 vaccine is also a form of crowdsourcing, albeit at a company level. However, for the purpose of the blog entry, the definition that will be applied is one by Darren C. Brabham who states in his book Crowdsourcing (The MIT Press Essential Knowledge Series, 2013. P. xxi. https://wtf.tw/ref/brabham.pdf) that crowdsourcing is “an online, distributed problem-solving and production model that leverages the collective intelligence of online communities to serve specific organizational goals.” Brabham goes on to say that one major factor to the online environment is speed and that “messages, and the exchange of ideas, can travel so fast along its channels … therefore accelerate creative development” (p. 12). The second definition is only in reference to online communities and to serve a specific organizational goal, while the first definition is too broad, almost akin with the call for help being thrown in to the wind. Our second definition works well with the various social media sites serving as hubs for crowdsourcing. And I would like to add, has allowed for user-to-user interaction.

And this brings us to Footprints and Facebook.

I became a Footprint contributor in October of 2020, the same time I started cataloging Hebrew incunabula at the Library of Congress. Cataloging a work into an online database, regardless of how many copies (or in our case, the number of owners a specific copy of work had), collapses all data into one bibliographic record. The Footprints Project database, on the other hand, identifies each owner of a specific copy of a book and gives each owner their own Footprint record. In the semantic web environment, each Footprint record is connected to that specific copy of the book, thus showing a relationship between the copy and each owner. I was learning all of this as I was learning to catalog the incunabula and learning how to input data into Footprints. Moreover, I was learning to pay closer attention to the marginalia and to look for clues concerning provenance.

Then one day in early November …

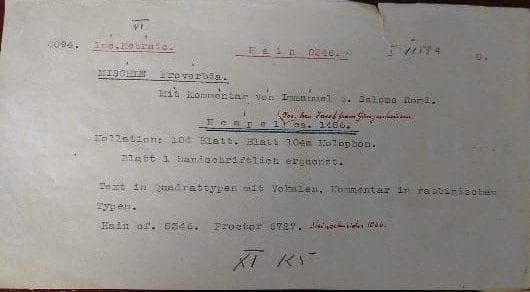

I was cataloging a 1487 printing of Immanuel of Rome’s commentary to the Book of Proverbs printed by Joseph ben Jacob Guzenhauser, the Ashkenazi in Naples, Italy. This particular copy was obtained by the Library of Congress from Otto Vollbehr through an act of Congress in 1930. Other than some marginalia, the book itself contained no owner identification — at least none that was obvious. There was a catalog record for the book, which was created by Vollbehr. In looking over the book, I noticed a label in German. My German is nicht gut. I decided to post a question on a Facebook group, Hebrew Codicology and Paleography, with the hopes of someone being able to help me make sense of what the label said. Then the magic of crowdsourcing started.

I was cataloging a 1487 printing of Immanuel of Rome’s commentary to the Book of Proverbs printed by Joseph ben Jacob Guzenhauser, the Ashkenazi in Naples, Italy. This particular copy was obtained by the Library of Congress from Otto Vollbehr through an act of Congress in 1930. Other than some marginalia, the book itself contained no owner identification — at least none that was obvious. There was a catalog record for the book, which was created by Vollbehr. In looking over the book, I noticed a label in German. My German is nicht gut. I decided to post a question on a Facebook group, Hebrew Codicology and Paleography, with the hopes of someone being able to help me make sense of what the label said. Then the magic of crowdsourcing started.

My post was posted to the group at 10:58am. At 11:02am came the first response – reading the German as “Hebr. Druck. no. 30”. At 11:04am, just two minutes later, a second response appeared– saying the label read “Hebr. Ink. Nr. 30”. I felt bad that the German did not give me a named owner. However, Michelle Margolis responded at 11:56am saying that this “no. 30” did come from someone’s collection. A few hours later, at 3:37pm, Dan Polakovic responded with “Mystery solved, see Nr 30” and a provided a link to Ludwig Rosenthal Antiquariat’s 1912 catalog at the Goethe University Library in Frankfurt. There was excitement in the air.  The clincher came when I posted the next image of the handwritten text on the inside front cover of the book at 3:44pm. And everything seemed to match. The key words in the book “Blatt 1 handschriftlich” matched the wording in the catalog. The first leaf in the book is a manuscript within the book, replacing the missing first printed leaf.

The clincher came when I posted the next image of the handwritten text on the inside front cover of the book at 3:44pm. And everything seemed to match. The key words in the book “Blatt 1 handschriftlich” matched the wording in the catalog. The first leaf in the book is a manuscript within the book, replacing the missing first printed leaf.

Within hours in one day, I went from not knowing the provenance of this particular copy to realizing (or perhaps being made to realize) the Library of Congress owned a copy sold by Ludwig Rosenthal in 1912.

In 2017, an initial record for the Rosenthal copy was created in Footprints. In 2020, I was able to complete this Footprints record. While Facebook and the Facebook group are examples of crowdsourcing, the Footprints project “relies in part on networked collaboration” (“Old Texts and New Media: Jewish Books on the Move and a Case for Collaboration” by: Michelle Chesner, Marjorie Lehman, Adam Shear, and Joshua Teplitsky in Digital Humanities, Libraries, and Partnerships: A Critical Examination of Labor, Network, and Community. Chandos Elsevier, 2018. P. 61 – 73. http://dx.doi.org/10.17613/M6X29M). Unlike library OPACs, where the cataloging is controlled by the individual library, Footprints is beyond the borders of the library, thus allowing others to contribute and also to finish a record once started by someone else.

Between crowdsourcing and networked collaboration, the origin of one book is identified, another footprint is accounted for, and another contribution is made to provenance scholarship.

Recent Comments