by Natalija Gligorevic

Natalija Gligorevic is an undergraduate student at the University of Pittsburgh who worked on Footprints in spring semester 2025 as part of the “First Experiences in Research” program for first-year students in the Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences at Pitt.

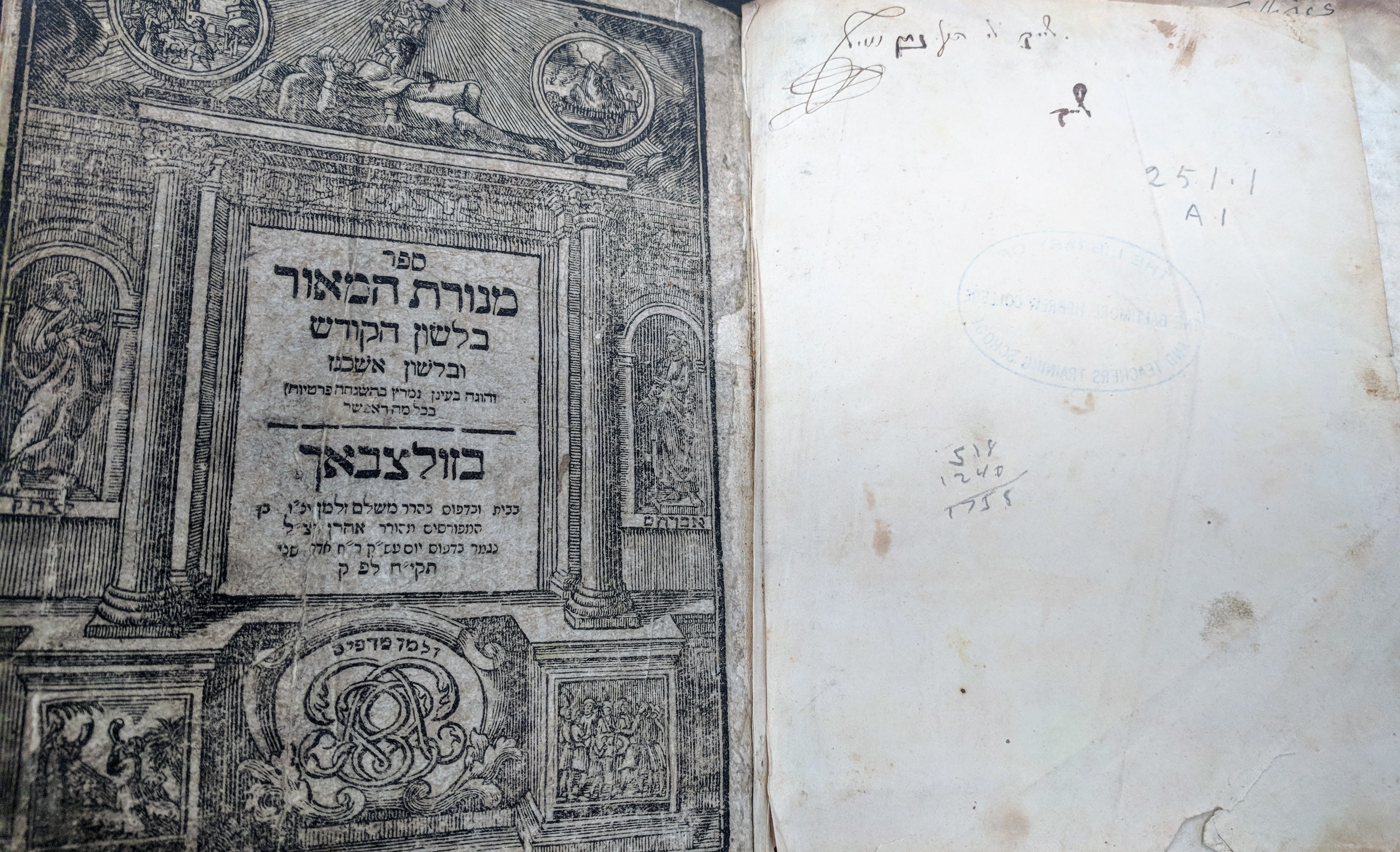

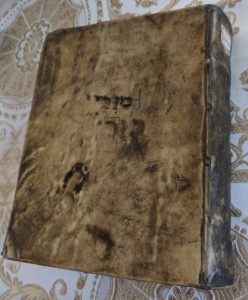

As part of my research internship with Footprints, I used my Serbo-Croatian language skills to explore the holdings of the Jewish Historical Museum in Belgrade, Serbia. I started with a catalog Izlozba Jezik, Pismo I Knjiga Jevreja Jugoslavije (Exhibition Language, Letters and Books from Jewish Yugoslavia) that was published in the old Yugoslavia in 1979. The catalog lists 164 total books in Hebrew and other languages, including 20 books printed before 1800. It also gives some basic information about the history of the collection although not as much as one would like.

Many of the books are shrouded in mystery, as there is a lack of matching records in databases such as the Library of Congress and WorldCat. As a result, my project not only added some new footprints and book copies to the database but even new imprints and literary works. One example is a book simply entitled Pizmon and printed in Venice in 1699” (no.74 in the booklist in Izloba Jezik). The entry labels this as a pesmarica, which means songbook in Serbian, a translation from the Hebrew title. The songbook’s function, based on the catalog’s description, was to be read and sung in the synagogue in Split, Croatia on the holiday of Simhat Torah. The only name that is connected to this book in the catalog is Rafael Pinso, who seems to have created “the second songbook” in Split in 1720 (see notes on Izloba Jezik item 74). There is not a lot of information about the author in the catalog nor on any online databases, leaving Pinso’s background and origin a mystery. But we do find something useful here–a connection with Split, which is a common denominator of many of the books in the Belgrade collection.

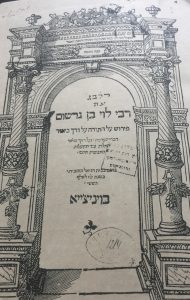

Another location that holds a strong connection to Belgrade’s museum is Venice, Italy. The majority of the books listed that were published prior to the nineteenth century were published in Venice by a variety of publishers. One of the oldest books in the catalog, Manot Halevi, a commentary on the Book of Esther by Solomon ben Moses (no. 61 in the booklist in Izloba Jezik), was originally published in Venice in 1584. Written in Safed in 1529, a copy of the first edition of the book eventually found its way to the museum. The book is the first edition. Son of Moses Alkabetz, Solomon Alkabetz was a prominent rabbi in the 16th century like his father. The circulation of his books casts a wide net, as Footprints shows copies of his books popping up in the Balkans, Israel, Italy, Amsterdam, and the United States.

Unfortunately, the date of acquisition for the books in the catalog have yet to be determined exactly due to a lack of information. The best I could do for the date of the footprint recording the acquisition of the book by the museum was a span from 1949 to 1979, representing the date of the founding of the museum and the date of publication of the catalog. However, I suspect, based on a report of a Jewish Material Claims Against Germany Conference, that many of the books were transferred from Macedonia to Serbia (“to the Jewish Museum in Belgrade, Serbia” during the communist era of the 1960’s.

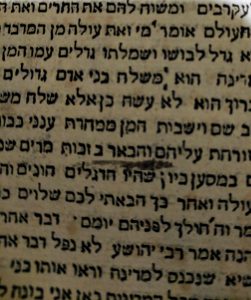

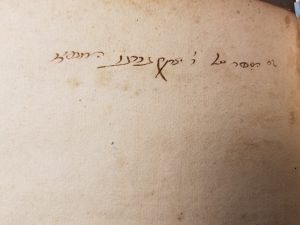

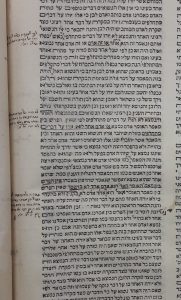

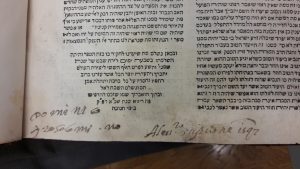

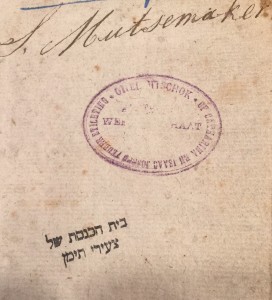

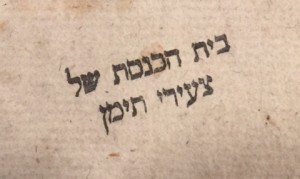

Another book published in Venice in the museum is Hemdat Jamim Lehodes Elul Ul’Jamim Noraim (aka Hemdat yamim in the English transliterations of the Hebrew). Published in Venice in 1763, it is the only book where a viable, verified second footprint was found. The second footprint involves a man named Rafael Giuseppe Leon Levi Mondolfo from Dubrovnik, Croatia. The catalog entry (no. 75) tells us that Rafael signed the book in 1819, confirming some sort of ownership of the book at that time. In his article, “The Levi Mondolfo Family: Jews of Rijeka and their Dubrovnik Roots,” Irvin Lukezic shows that Rafael’s family roots were planted in central Italy, and his ancestors moved to Dubrovnik after the seventeenth century followed by a move to Rijeka, Croatia later on. Rafael was the son of a merchant and a prominent member of the Rijeka Jewish community. Levi Mondolfo, Rafael’s father, was voted vice president of the community in 1838 and president in 1840. Rafael followed in his father’s footsteps, keeping close ties with his faith while inheriting the family’s merchant business. One signature in one book led me to an entire lineage and history of Croatian Jews, naming prominent and influential members such as the Mondolfo family.

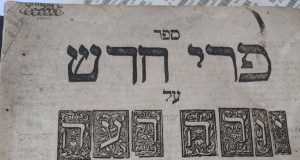

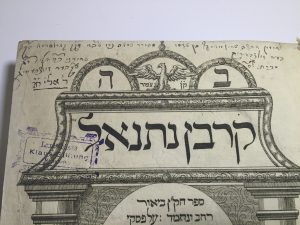

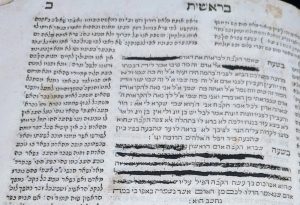

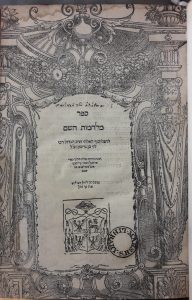

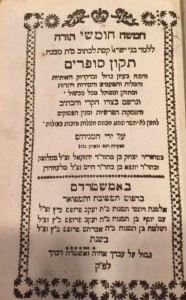

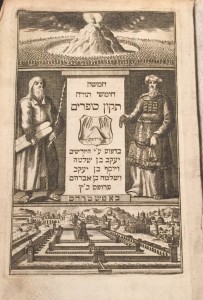

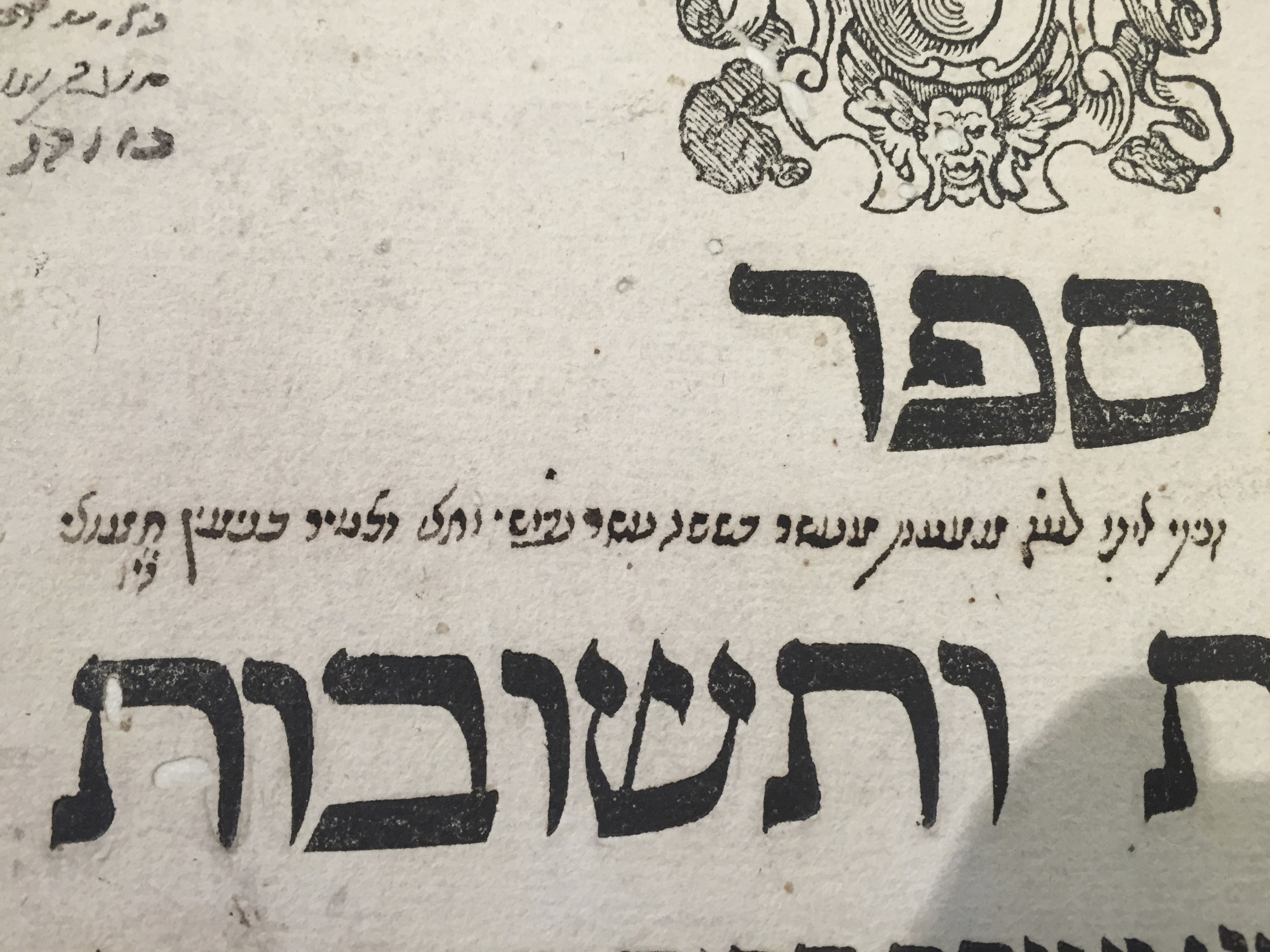

Three versions of Joseph Caro’s law code, the Shulhan Arukh, can be found in the collection: an edition printed in Amsterdam, 1753 (no. 67); the Libro de mantenimiento del Alma, a Spanish translation and adaptation by Rabbi Moses Altaras, published in 1609 in Venice (no. 64); and Aruh Hakacur (Arukh ha-Katzur), an abridgement published in Prague in 1707 (no. 66).

Overall, this catalog provided both new literary works and footprints for the database. Serbia and the Balkans are mostly an untouched region for Footprints, and this catalog was an informative introduction of the kind of history and literature that the Jewish community had there. With further research, especially examination of the books themselves in Belgrade, more connections and discoveries will arise.

References:

Klepal, Jakub, et al. “Holocaust Era Assets Conference.” Forum 2000 Foundation, Holocaust Era Assets: Conference Proceedings: Prague, June 26-30, 2009, 2009, pp. 5–26, www.claimscon.org/forms/prague/Judaica.pdf#:~:text=Some%20Judaica%20from%20Macedonia%20was%20transferred%20during,to%20the%20Jewish%20Museum%20in%20Belgrade%2C%20Serbia.

Lukežić, Irvin. “The Levi Mondolfo Family: Jews of Rijeka and Their Dubrovnik Roots.” Anali Zavoda za povijesne znanosti Hrvatske akademije znanosti i umjetnosti u Dubrovniku, no. 56/1, 2018, pp. 363-411. https://hrcak.srce.hr/index.php/199726. Accessed 11 Feb. 2025.

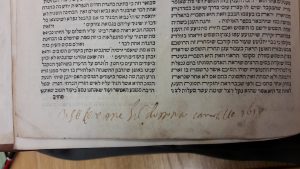

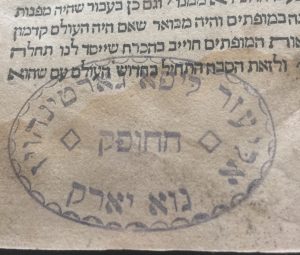

The third footprint was a stamp in purple ink indicating that the book had been owned by

The third footprint was a stamp in purple ink indicating that the book had been owned by

Recent Comments