by Fabrizio Quaglia

This is the third in a series of posts by Fabrizio Quaglia on his ongoing work collecting Footprints and other data from the collection of David Kaufmann, now at the Hungarian Academy of Sciences in Budapest. As Quaglia notes, the collection is multilayered, revealing libraries within libraries.

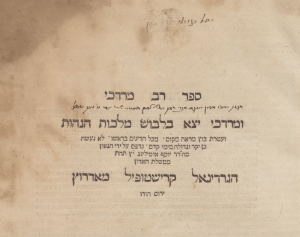

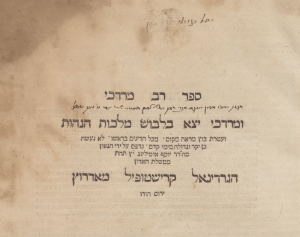

Title Page with Aharon Ya’akov Segre inscription

Moving towards Western Italy is the small city of Chieri, near Turin. The cursive Hebrew purchase note of one of its inhabitants, Aharon Ya‘akov Segre, father of Netan’el Segre (1623-1691), rabbi in Cento (Ferrara), is readable on the title page of the compendium of the legal Ashkenazic traditions Sefer rav Mordekhai (Riva di Trento, 1558) by the German rabbi Mordekhai b. Hillel (1240?-1298), “From his own money, Aharon Ya‘akov Segre from the honored teacher Yitṣḥak Mesṭre – may his Rock keep him and grant him life – day 9 Ṭevet 386 [C.E. 7 January 1626]” (Kaufmann B 556).[1]

The Sefer rav Mordekhai was previously owned by Yitshak Mesṭre about whom no information was found. His origin is surely from Mestre, a town near Venice. A “Guglielmo di Elia da Mestre” was a pawnbroker in Florence in the 1480s. Later the birthplace “da Mestre” became the surname Mestre. In 1605 a rabbi called “Emanuel Mestre,” probably resident in Casale Monferrato, was one of three Jewish judges summoned to resolve a quarrel regarding the heritage of the influential Simon son of Vitale Sacerdote of Alessandria. As a result of what has been reported as well as for the chronological proximity of the abovementioned signatures of Segre, one can guess that Yiṣḥak Mesṭre was a Piedmontese Jew, too.[2]

A stop in the Marche region

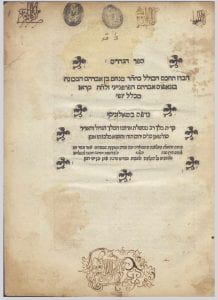

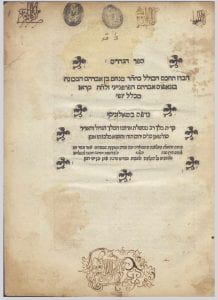

Title Page with Asher Viterbo inscription

Asher Viṭerbo (active 1748-1800)

Asher Viṭerbo (recorded in Italian documents as Anselmo Viterbo) lived South-East of Emilia, in Pesaro, in the seventeenth century. Viterbo owned the Sefer ha-ḥasidim, printed in Bologna in 1538 (Kaufmann B 293; first edition). Asher was the son of Shimshon Viṭerbo (Sansone Viterbo) of Pesaro, an eminent member of the Jewish community of Pesaro, a rabbi (although never chief rabbi), and a poet (he authored two published wedding poems containing riddles as was customary at the time, and in 1780s celebratory verses for the circumcision of the unnamed son of a certain rabbi Refa’el Shimshon ha-Levi from Pesaro). In 1773, Asher corresponded in 1773 with the rabbi of Florence, Dani’el b. Mosheh David Ṭerni on the resurrection of the dead and on metempsychosis (which for Viterbo was a superfluous occult doctrine); and in 1799 he corresponded with Mattatyah Nissim Ṭerni (b. 1745), a rabbi living in the Marche. All of these letters are contained in Ṭerni’s book of rabbinical responses, Midbar matanah, printed in Florence in 1810. Twenty-one letters from A. Viterbo, years 1780-1800, addressed to the distinguished Hebraist Piedmontese Giovanni Bernardo De Rossi (1742-1831) are kept in Parma, Biblioteca Palatina; Viterbo gave De Rossi a fifteenth-century book of Psalms on parchment.[3] We can reconstruct Viterbo’s library thanks to his signature, which includes is name and surname placed between two equal signs, and appears on 13 manuscripts, including a sixteenth-century miscellany of texts by Italian Jews (ms. Kaufmann A 504), and a number of books (two of them are incunables), treasured in the libraries of Budapest (also in the Library of the Jewish Theological Seminary – University of Jewish Studies), Hamburg, Jerusalem, London, Moscow, New York (Jewish Theological Seminary and Columbia University Library), Oxford, Parma, Piacenza, Trento and in the Vatican.[4]

Other owners from Marche

According to what one can read in handwritten form on the books he owned, the now missing Kaufmann B 206, Venice 1550, and B 207, Ferrara 1552, Efrayim Ḥay b. Maṣliaḥ Ḥay was born on 10 December 1562, perhaps in Jesi (Marche). Since both volumes (bound together, in the distinctive Mortara binding) concern the topic of the ritual slaughtering, shehitah, Maṣliaḥ Ḥay who signed the verso of the title page of Kaufmann 206 was probably a bodek (lit. “checker”) or a shohet. These assignments were sometimes carried out by the same man. Efrayim Ḥay could have exercised the alleged profession of his father in Jesi and in a locality belonging to the Republic of Venice, as he declared on f. [8]r of Kaufmann B 207. Efrayim Ḥay certainly had a brother called Yiṣḥak, as he reported at the top of f. [2]r of Kaufmann B 206, and could have had a scion named Efrayim Shemu’el, who wrote in Hebrew a peculiar ownerʼs note at the end of the same volume, slightly cropped and faded at the left margin: “People sign their books from the beginning of time lest someone come from the market and say ‘This is mine’ thus I wrote my name Efrayim Shemu’el …”.[5] On f. [8]v of Kaufmann B 207 Efrayim Ḥay wrote that his father was the son of a certain Moshe from Ascoli (Marche).

Title page with signatures of Shemu’el ben ‘Immanu’el Hamis

This quick walk-through of Marche ends with a book owner who perhaps was not originally from this region. On the title page of Sefer ha-gedarim, Saloniki 1567 (Kaufmann B 134; first edition, also in the libraries of S.V. Dalla Volta and Mortara) – there are four 17th-century Sephardic signatures, all of them written by the same person: Shemu’el b. ‘Immanu’el Ḥamiṣ. The surname Ḥamiṣ belongs to a Marrano family of merchants (chiefly leather and cloths) from the Iberian Peninsula, who settled in various Italian communities after the expulsion of the Jews from Spain. Indeed, in the 16th and 17th centuries we can identify traces of Camis and Camiz (so in Italian documents) in Ancona, Ferrara, Genoa, and Venice, from where they traded with the ports of Livorno and Tunis. A certain Samuel Camis (also called Camizi), who in 1613 was in Tunis for a short term, was perhaps the same man who in 1594 was appointed as one of the two delegates of the Levantine Congregation of the Jews of Ancona. A “Samuel Camiz” was censused in Ferrara with his family in 1692 when he was 55 years old. One of them could have been the owner of Kaufmann B 134, but it cannot be sure because it is not known whose sons the people mentioned were. We also see a Shemu’el Ḥamiṣ, who copied the Magen Avraham in (ms. 77 A of the Library of the Alliance Israélite Universelle in Paris).[6]

[1] Apparently, the same A.Y. Segre wrote marginal glosses, some underlines, and a few corrections that one can notice on several folios of this thick volume. A.Y. Segre bought from Šemaryah b. Yehudah Qonian (Conian, from Conegliano in the Treviso province) of Asti on 8 October 1626 an Ashkenazic copy on parchment dated 1394 of Sefer ha-Šorašim (“Book of Roots”) by David b. Yosef Qimḥi (1160-1235) – which is the Cod. 3050 of the Palatina Library of Parma (his purchase note is on f. 2r). On 19 October 1626 Segre purchased by Qonian an Ashkenazic mid-to-late 14th-century handwritten collection of nine legal texts on parchment, the Cod. 2592 of Palatina Library (his purchase note is on f. 2r here too). Flaminio Servi, Cenni storici sulla comunione israelitica di Cento, “L’Educatore israelita”, XIII, 1865, 9, p. 265; Elliott Horowitz, A Jewish Youth Confraternity in Seventeenth-Century Italy, “Italia”, V, 1985, 1-2, pp. 69, 77, 89; Hebrew manuscripts in the Biblioteca Palatina in Parma. Catalogue; edited by Benjamin Richler; palaeographical and codicological descriptions, Malachi Beit-Arié, Jerusalem, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Jewish National and University Library, 2001, nos. 875, 1441, pp. 196, 417.

[2] Archivio di Stato di Alessandria, Fondo notarile, Notaio Giovanni Marco Pandino, Registro 908 (it is a notarial deed drawn up in Alessandria on 21 September 1605); La comunità ebraica di Venezia e il suo antico cimitero; Ricerca a cura di Aldo Luzzatto, I, Milano, Il polifilo, 2000, p. 360; Michele Luzzati, La circolazione di uomini, donne e capitali ebraici nell’Italia del Quattrocento: un esempio toscano-cremonese, pp. 44-45, in Gli Ebrei a Cremona. Storia di una comunità fra Medioevo e Rinascimento; a cura di Giovanni B. Magnoli, Firenze, Giuntina, 2002; Elvio Giuditta, Araldica Ebraica in Italia, Torino, Società Italiana di Studi Araldici, 2007, p. 222.

[3] MS. 1716 of Palatina –– the gift note is on f. 192v

[4] Catalogue of the Hebrew Manuscripts in the Bodleian Library; compiled by Adolf Neubauer, Oxford, at the Clarendon Press, 1886, no. 361, col. 76; George Margoliouth, Catalogue of the Hebrew and Samaritan Manuscripts in the British Museum, I, London, British Museum, 1899, no. 198, p. 150; III, 1915, no. 978, pp. 305-306; Giuseppe Gabrieli, Manoscritti e carte orientali nelle biblioteche e archivi d’Italia, Firenze, L.S. Olschki, 1930, p. 87; Israele Zoller, Per la storia delle famiglie ebraiche in Ancona nella seconda metà del Settecento, “La Rassegna Mensile di Israel”, VI, 1931-1932, 11-12, pp. 534-535, 543-544; Dan Pagis, Baroque Trends in Italian Hebrew Poetry as Reflected in an Unknown Genre, pp. 267, 274, in Italia Judaica. II. Gli ebrei in Italia tra Rinascimento ed età barocca. Atti del II Convegno internazionale Genova 10-15 giugno 1984, Rome 1986; D. Pagis, ‘l sod ḥatum. Le-toledot ha-ḥiddah ha-ivrit be-Iṭaliah we-be-Holland (“A secret sealed. Hebrew Baroque Emblem-Riddles from Italy and Holland”), Yerušalayim, Magnes, [746] 1986, pp. 77, 145, 157 [in Hebrew]; Werther Angelini, Momenti dell’attività e dell’incidenza ebraica tra Cinquecento e Settecento nelle piazze di Ancona, Senigallia e Pesaro, pp. 43-44, in Cultura e società nel Settecento. 2. La vita economica nelle Marche, Urbino, Arti grafiche editoriali, 1988; Gardens and Ghettos. The Art of Jewish Life in Italy; edited by Vivian B. Mann, Berkeley, University of California Press, 1989, no. 161a, p. 281; Viviana Bonazzoli, Sulla struttura familiare delle aziende ebraiche nella Ancona del ‘700, pp. 149, 153, in La presenza ebraica nelle Marche. Secoli XIII-XX; a cura di Sergio Anselmi e V. Bonazzoli, Ancona, Proposte e ricerche, 1993; Maria Luisa Moscati Benigni, Marche. Itinerari ebraici. I luoghi, la storia, l’arte, Venezia, Marsilio, 1996, p. 125; Hebrew manuscripts in the Biblioteca Palatina in Parma. Catalogue, no. 397, p. 80; David Malkiel, The Rimini Papers: A Resurrection Controversy in Eighteenth-Century Italy, “Journal of Jewish Thought and Philosophy”, XI, 2002, 2, pp. 89-96, 104, 114; V. Bonazzoli, L’economia del ghetto, pp. 22, 59, 61, in Studi sulla comunità ebraica di Pesaro; a cura di Riccardo Paolo Uguccioni, Montelabbate, Fondazione Scavolini, 2003; A. Salah, Le République des Lettres. Rabbins, écrivains et médecins juifs en Italie au XVIIIe siècle, Leiden, Brill, 2007, no. 1021, p. 658; Renata Segre, Gli ebrei a Pesaro sotto la Legazione apostolica, pp. 174, 184, in Pesaro dalla devoluzione all’illuminismo, IV, Venezia, Marsilio, 2009; Marvin J. Heller, The Seventeenth Century Hebrew Book, I, Leiden, Brill, 2011, p. 544; Kedem, Online Auction no. 15, Jerusalem, 2018, lot 82; website MEI. Material Evidence in Incunabula, <https://data. cerl.org/mei/02124954> and <https://data.cerl.org/mei/02137658>; Biblioteca Digitale Trentina, <https://bdt.bibcom. trento.it/Testi-a-stampa/19#page/n137>.

[5] This is not an unusual way to claim ownership of a book, cf. Annabel Gallop, Hands off! This book is mine! Ownership inscriptions in Hebrew manuscripts, in the Asian and African studies blog of the British Library, <https://blogs.bl.uk/asian-and-african/2020/03/hands-off-this-book-is-mine-ownership-inscriptions-in-hebrew-manuscripts.html>.

[6] Michele Cassandro, Aspetti della storia economica e sociale degli ebrei di Livorno nel Seicento, Milano, Giuffrè, 1983, pp. 71, 79, 121 (note 312); Robert Bonfil, Rabbis and Jewish Communities in Renaissance Italy, Liverpool, Liverpool University Press, 1989, p. 172 (note 316); Rossana Urbani and Guido Nathan Zazzu, The Jews in Genoa, I, Leiden, Brill, 1999, docs. 647-648, 683-685, 689, 698; La comunità ebraica di Venezia e il suo antico cimitero, pp. 305-306, 313, 523; Giuliana Boccadamo, Mercanti e schiavi fra Regno di Napoli, Barberia e Levante (secc. XVII-XVIII), pp. 252-253, in Rapporti diplomatici e scambi commerciali nel Mediterraneo moderno. Atti del Convegno internazionale di studi [Fisciano 23-24 ottobre 2002]; a cura di Mirella Mafrici, Soveria Mannelli, Rubbettino, 2004; Elia Boccara, Gli ebrei italo-iberici presenti a Tunisi (o in relazione con Tunisi) dalla conquista turca al regno di Yusuf Dey, pp. 133-134, 141-142, 156-157, 171-172, in Percorsi di storia ebraica. Atti del Convegno internazionale (Cividale del Friuli-Gorizia, 7-9 settembre 2004); a cura di Pier Cesare Ioly Zorattini, Udine, Forum, 2005; E. Boccara, In fuga dall’inquisizione. Ebrei portoghesi a Tunisi: due famiglie, quattro secoli di storia, Firenze, Giuntina, 2011, pp. 67, 75, 87; L. Graziani Secchieri, «In casa d’Amadio Sacerdoti Mondovì: lui medesimo d’anni 35». Il censimento del ghetto di Ferrara del 1692, p. 140, in Ebrei a Ferrara. Ebrei di Ferrara. Aspetti culturali, economici e sociali della presenza ebraica a Ferrara (secc. XIII-XX). Atti del Convegno internazionale di studi (Ferrara 3-4 ott. 2013) Fondazione Museo Nazionale dell’Ebraismo Italiano e della Shoah; a cura di L. Graziani Secchieri, Giuntina, Firenze 2014.

Recent Comments