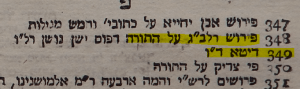

Ed. note: When we began our work on Footprints, we quickly realized that William Popper’s Censorship of Hebrew Books was going to be critical to identifying expurgators, and the places and dates where they operated. Although over one hundred years old, Popper’s seminal work identifies many censors by their dates and locations, and includes images of their signatures in printed books. Kate Cornelius, a student at the University of Pittsburgh, thus created a spreadsheet of the censors found in Popper, and we refer to it constantly in Footprints research. Over time, though, we have found errors and omissions in Popper, and have been able to correct them in the spreadsheet. Fabrizio Quaglia has been a tremendous help in updating our “digital Popper,” and below writes about what he has discovered along the way.

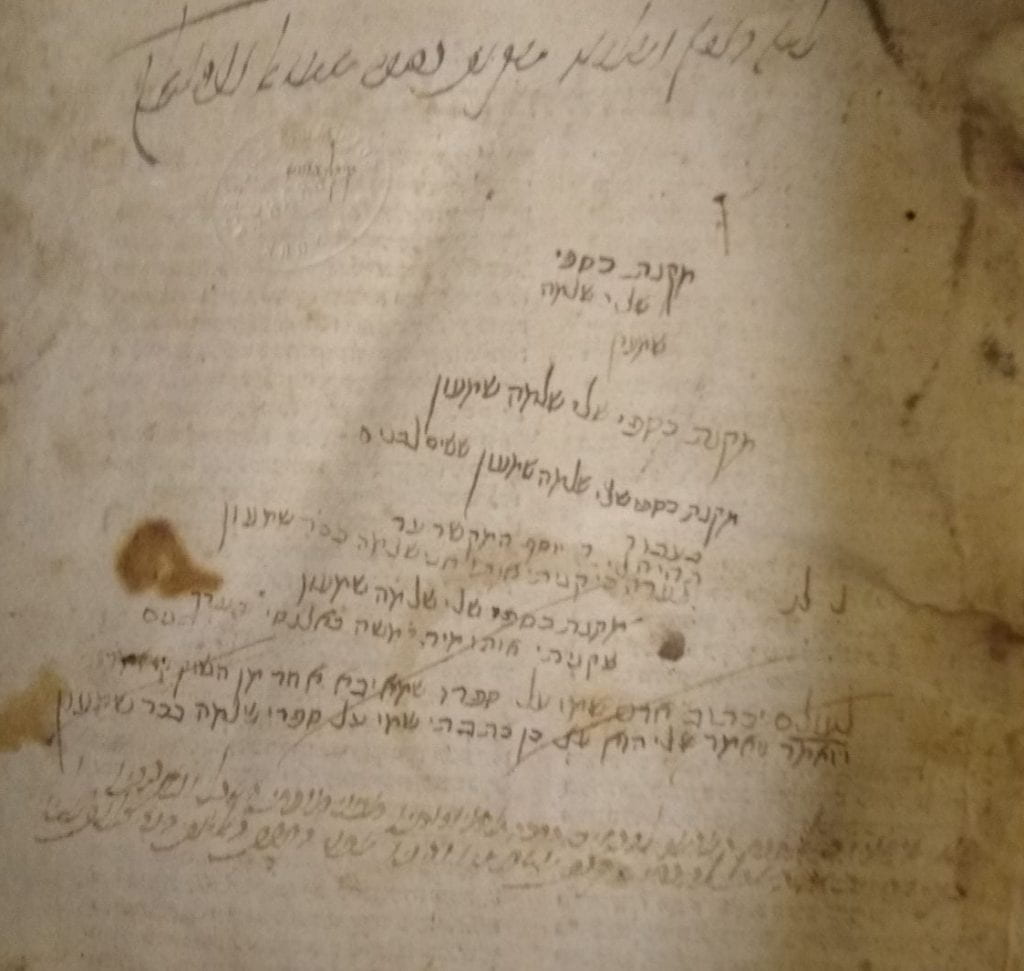

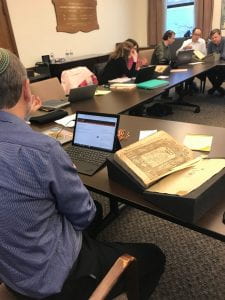

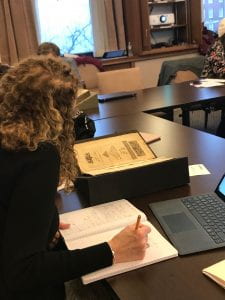

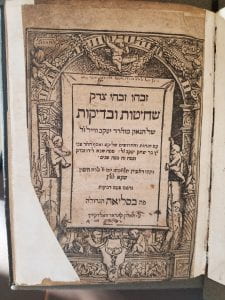

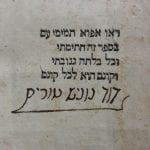

A book is a physical object but not an isolated object. Beyond its content there may be a treasure trove, breathing with the air of time and exuding with the hands of its readers whose written or stamped traces are visible on its pages. The study of provenance of a book can reveal a way of thinking and even dreaming. In case of Hebrew and Judaic books it also assumes the peculiar value of testimony; a faded name in a purchase note written on a torn page can be the only persisting legacy of a lifetime, and library stamps and bookstore stickers often hide stories of suffering and painful migration. Examining such a paper heritage provides new sources to historians of Jewish communities, to scholars in general, to private collectors, and to paleographers, archivists and librarians. All of them should unite their skills, sharing their findings so to get better results.

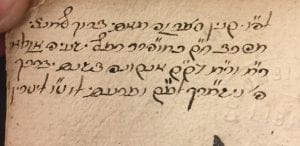

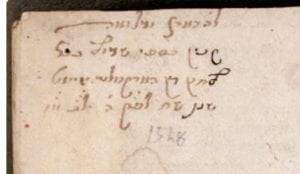

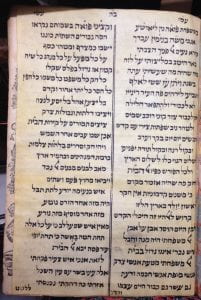

A particular example of this kind of collaboration can be given by the centuries-long censorship of Hebrew texts, whose traces have come down to us. A historian of Jewish communities of Italy can take advantage of these annotations, discovering the reading habits of indidivuals and movements of a text from one nation to another. Ironically, “thanks” to censorship I detected the presence in Piedmont of an interest in Kabbalah often neglected or even denied. For this reason, it is important to determine correctly the date of a censor-mark.

Reading the signature of a Giovanni Antonio Costanzi or a Domenico Gerosolomitano we must remember that these revisors of Hebrew books were often converted rabbis that abandoned their faith and congregation for a zealous work of censor, sometimes combined to a teaching post where their task was to give to the Catholic church learning enough to convert Jews. The same Gerosolomitano, and also Renato da Modena and others, compiled manuals for the emendation of Hebrew books, where “dangerous” titles and words were detailed. The handwritten Sefer ha-ziqquq is a known example, but there are others as well. I detected a reference to a similar index used in Asti, Piedmont, in a signature belonging to friar Vincenzo de Matelica (born circa 1549), another apostate revisor (and former rabbi).

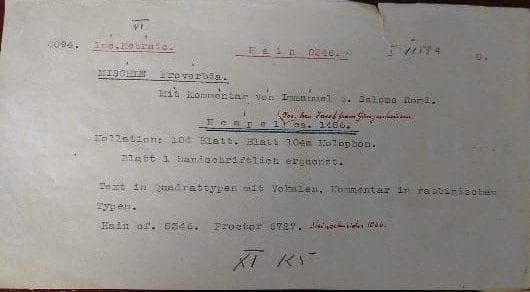

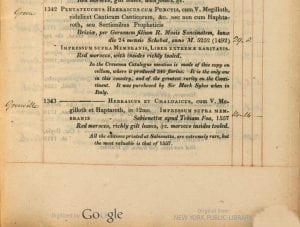

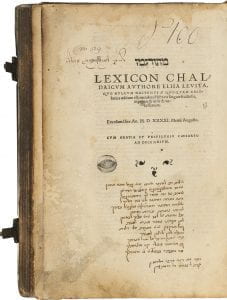

Some of these expurgators were reported in a fundamental book: The Censorship of Hebrew Books, published in New York in 1899. The work was the doctoral dissertation of William Popper (1874-1963). He was a student at Columbia University where he received degrees of A.B. in 1896, A.M. in 1897, and his Ph.D. in 1899. Professor of Semitic Languages at Berkeley, Popper was one of the greatest figures among American Orientalists, specializing in Hebrew and Arabic studies. The Censorship of Hebrew Books is the fruit of a deep research inside the collections at Columbia, and using the work of other Hebraists, putting in the appropriate context of the signatures he found. It is still deservedly used today as a primary reference book for scholars and librarians in USA, Europe and Israel, but it was written in a period when study of censors’ inscriptions was unavoidably limited to some libraries where photocopying (let alone scans) was not yet possible and few articles and catalogs circulated on Hebrew censorship; in addition his survey was restricted to the signatures he directly or indirectly knew. Above all, he worked in a definitely pre-Internet era. Year after year biographical information on censors has increased: to name a few examples, we have since learned that:

Petrus de Trevio is also known as Pietro Pichi;

Renato da Modena’s name before he took religious orders was Renato Corradini;

“Gio. Monni” is friar Giovanni da Montefalcone, General Inquisitor of Modena, born Giovanni Ghermignani (d. 1599).

Sometimes we are able to add additional information about expurgators based on material that Popper did not see. For example, Popper informs us of the stay of the monk Antonio Francesco Enriques as censor in Urbino in 1687. But he was also in Alessandria as the censor in 1688 — I found his signature ending with “Aless[andri]a 1688” on several Hebrew manuscripts and books.

Most significantly, perhaps, Popper listed few Italian sources among the authorities he cites (mainly Abraham Berliner, Adolf Neubauer, Moritz Steinschneider and Leopold Zunz). The exceptions are Giovanni Bernardo De Rossi and Isidoro Bianchi’s book Sulle Tipografie Ebraiche di Cremona (printed in 1807). This might explain why his readings of censors’ notes are not always accurate. He studied and traveled in Europe and Near East, but perhaps he never learned Italian. Moreover, the Italian script of XVI-XVIII centuries is not simple to understand because of certain features in calligraphy and abbreviations, a fact that still causes difficulties. Lastly, some censor-marks he included did not belong to expurgators, as I will explain.

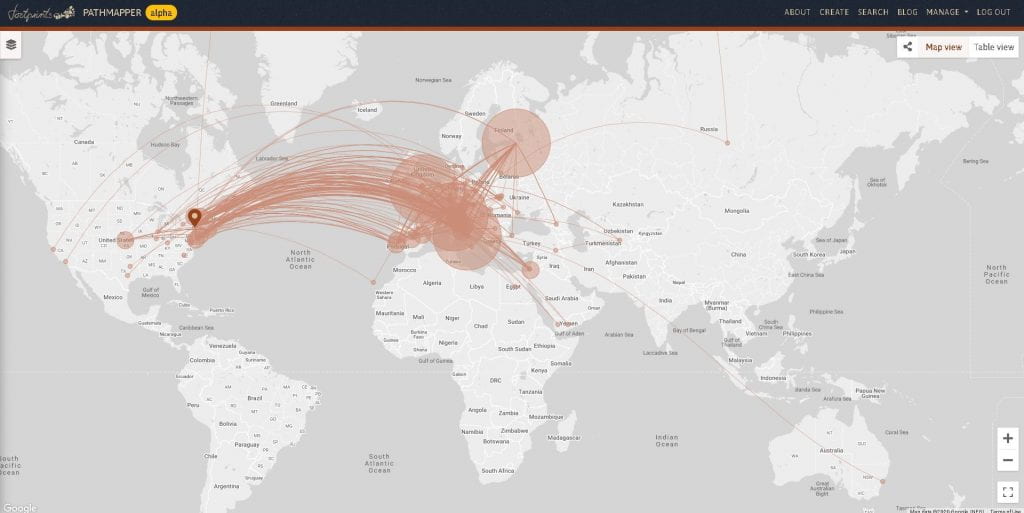

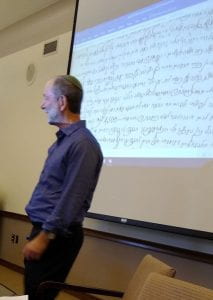

All this being said, we contemporaries are all dwarfs on the shoulders of Popper, because he explored an almost unknown land with few companions. Today one just presses a button on a keyboard to send a photos overseas with a blink of an eye. In a digital world it is much easier than before to decipher obscure words comparing and editing images and surfing the internet in search for related information. And websites like Footprints record and connect information on Ashkenazic, Sephardic, Italian and Oriental Hebrew ownership, on Italian, Russian and Polish censorship, as well as owners’ notes in French, Latin, German, and so forth.

For this reason, at the suggestion of Michelle Chesner, I have been compiling short bio-bibliographic records correcting several mistaken names in Popper. I have been collecting information from published sources at my disposal (mostly in Italian and not well-known to the international scholarly community), checking the original signatures on scanned books and manuscripts, and adding some information on the activities of censors themselves. In some cases I discovered their real identity hidden under the religious dress. Here I will present only some abridged instances of my research among the revisors, inquisitors and notaries that Popper discussed (sometimes erroneously). Many of these findings also have been added to Footprints records.

Sometimes Popper’s interpretation of names comes quite close to the correct reading. Alexander Caius (per Popper) is Alessandro Cari. The correct reading of “Alexandro Cari” was already in The Jewish Encyclopedia, V, p. 652, s.v. “Censorship of Hebrew Books.” Antonio Maria Biscioni, Bibliothecae Mediceae-Laurentianae. Catalogus […] Tomus Primus codices orientales complectens, Florentiae, Ex Imperiali Typographio, 1752, p. 13, had already printed the Latin signature “Alixandro de Cari revedetor [revisor]” that he saw at the end of Cod.Plut.I.15. Moreover A.M. Biscioni, p. 57, indicating Cari’s approbation to Cod. Plut. I.57. In this case it had previously been noticed by Bernard de Montfaucon, Bibliotheca bibliothecarum manuscriptorum nova, I, Parisiis, Briasson, 1739, p. 242. Others have had readings that followed or echoed Popper’s: Carlo Berneimer, Paleografia ebraica, Firenze, Olschki, 1924, pp. 180 and 399, called him “Alixandro de Cavi.”In Giulio Busi, Edizioni ebraiche del XVI secolo nelle biblioteche dell’Emilia Romagna, Bologna, Analisi, 1987, nos. 63 and 340, he is indexed as “Alixandro de Caij.”

Joseph Ciantas (who Popper inadvertently also called Cronti) is the Dominican friar Giuseppe Ciantes (1602-1670). A similar slight misinterpretation concerned the eighteenth-century friar Paracciani, who Popper read as “Parcicciani.” This name was already correctly reported in A. Berliner, Censur und Confiscation hebräischer Bücher im Kirchenstaate, Frankfurt a. M, J. Kaufmann, 1891, p. 30 (a source that Popper used). In Popper’s entry on “Girolamo da Durallano” the place of origin should be corrected to Durazzano (hence Girolamo da Durazzano), a small town in the province of Benevento in Campania (South Italy). It is an understandable mistake due to the way Girolamo wrote the letter z almost identical to the letter l. This has been corrected by Mauro Perani, Confisca e censura di libri ebraici a Modena fra Cinque e Seicento, in L’ Inquisizione e gli ebrei in Italia, a cura di Michele Luzzati, Bari, Laterza, 1994, pp. 312 and 319, note 75, but even recently I have seen online catalogs with “Durallano”. An image of his signature appears in Footprints. A few others: “Hier. Carolus” is Girolamo Caratto, inquisitor at Asti from 1566 to 1589; Dionysus Sturlatus is Dionisio Sburlato, “Vic[ariu]s” (meaning “deputy”) of inquisitor Alessandro Longo in Mondovì (in the province of Cuneo in Piedmont). Bartolomeo Rocca di Præterino is Bartolomeo Rocca di Pralormo, inquisitor of Turin from 1588 to 1598 (as well as of Cuneo, Fossano and Nizza Monferrato, all Piedmontese towns).

Rocca di Pralormo’s censorship is often linked to that of friar “Paulus vicecomes”, whose Italian name was Paolo Visconte. He was born in Alessandria, or in some nearby towns in the diocese of Alessandria. “Vicecomes” is his surname and does not mean “vicarius” as Popper thought (p. 89, note 327).

A geographical mistake regards the above-mentioned Alessandro Longo. Popper wrote that he was revisor at Monreale, a place in Southern Piedmont near Asti. So he read in Friedrich H. Bischoff und Johann H. Möller, Vergleichendes Wörterbuch der alten, mittleren und neuen Geographie, Gotha, 1829, p. 763; where, however, it is called Mons Regalis – namely Montreale! Unfortunately the fact that Popper had turned the real name of this town into Monreale has created confusion with the Sicilian town where in truth in the years 1570-1606, when Longo was inquisitor, there were no Jews with books to be censored. For this reason I specified that “Montiregalis” is the old Latin name of Mondovì. This kind of misunderstanding generates a funny situation with respect to Vincenza Suppa. Vincenza is a female name and expurgation was a man’s world. In fact it is Vincenzo Suppa, a man who was “Regio censore in Livorno” from 1825 until 1832, when he was fired from his job for lack of zeal in censoring Italian political texts.

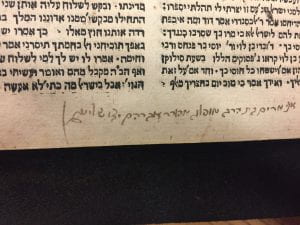

In other cases a well-known name hides under an invented one: Domenico Cacciatore is the 17th-century expurgator Giovanni Domenico Carretto, whose censor’s marks can be found in many Hebrew texts. Popper, who suspected what his true identity was, referred to an article in “Hebräische Bibliographie”, V, 1862, p. 76, note 13, which in turn referred (with similar doubts) to Die handschriftlichen hebräischen Werke der K.K. Hofbibliothek zu Wien, Wien, K.K. Hof- und Staatsdruckerei, 1847, no. 13. Indeed, Popper and the author of the 1862 article were correct in being suspicious of the 1847 catalog which had mistaken the original “visto per me Gio. dominico carretto 1618” in Cod. Hebr. 28 of Austrian National Library, folio 400v. The correct reading can be found in Arthur Zacharias Schwarz, Die hebräischen Handschriften der Nationalbibliothek in Wien, Leipzig, Karl W. Hiersemann, 1925, no. 19.

It is understandable that Popper had troubles with some of the signatures that were more difficult to decipher like “Bernard[us] Nucetus not[ariu]s. SS. Officii Parmae”. Bernardo Noceto was an ecclesiastical notary who endorsed expurgation of Hebrew texts on behalf of the Inquisition in Parma, but Popper read him “Heuesas”. In fact, it was so misinterpreted in recent years as well: see Christie’s, New York, auction catalog Hebrew Printed Books. Duplicates from the Library of The Jewish Theological Seminary of America, Thursday 22 May, 1986, lots 38, 43, 44 (but without certainty in identification); and Edizioni ebraiche del XVI secolo del Centro Bibliografico dell’ebraismo italiano dell’Unione delle comunità ebraiche italiane. Catalogo, a cura di Amedeo Spagnoletto, Roma, Litos, 2007, nos. 30 (signed on 1619), 96a, 240. Another case concerns the preacher to the Roman Jews Gregorio Boncompagni degli Scarinci (d. 1688 at 77). Popper, at p. 139, no. 48, indicated him as Boncampagno Marcelleno, and at p. 145, no. 118, as Marcellino. His signature “Gregorius Boncompanius expurgator deputatus” is abbreviated, however, in Casanatense Library of Rome, Ms. 2925, f. 162r; see Gustavo Sacerdote, Catalogo dei codici ebraici della Biblioteca Casanatense, no. 61 in Cataloghi dei codici Orientali di alcune Biblioteche d’Italia, VI, Firenze, Stabilimento tipografico fiorentino, 1878. Even more complex is “Nico. de Sorzone.” Popper misread, as did A. Neubauer, Catalogue, I, no. 655, the censorship in Ms. Oxford, Mich. 8. They reported it as “Nico. de Sorzome 1602.” But I have been able to see, thanks to a scanned reproduction, the correct inscription. Thus, on f. 168v, partly blurred, I read “corretto p[er] me gio[vanni] domi[nico] di comissione del M.[olto] R.[everendo] P.[adre] uic:o [= vicario] de sarzana a li 12 feb.[brai]o 1602”; below, partly crossed “Ita e[tiam] fr’ Ang[elu]s Capillus vic[ariu]s s[anc]ti officij”. Hence I found out that the real censor was the unknown Giovanni Domenico da Lodi (Lodi is in Lombardy). He wrote “a” in a very similar way to “o”, consequently Sorzome/Sorzone was intended for Sarzana. Sarzana is a town near La Spezia in Liguria, a seat of a vicariate of Holy Office, whose person in charge (a priest collaborator of the bishop) evidently ordered Giovanni Domenico to expurgate Hebrew texts. The aforementioned Holy Office deputy Angelo Capello was probably the man who had to supervise the expurgations made by Giovanni Domenico in that diocese. Capello was from Brescia as we learn from his declarations of his birthplace–“de Brixia” in other censored Hebrew manuscripts.

Some censors named by Popper simply never existed, but were created by misunderstanding: Clemente Carretto was actually (once again) Giovanni Domenico Carretto, and Jacob Gentiline was a wrong reading of Jacob Geraldino. In other cases, Popper names real people as censors who were not: the very famous French essayist Michel de Montaigne actually existed but he was not a Hebrew expurgator; Popper wrongly put him in his alphabetical list of censors at the end of his volume. Apparently he read Hermann Vogelstein and Paul Rieger, Geschichte der Juden in Rom, II, Berlin, Mayer & Müller, 1895, p. 172, who read Montaigne’s Journal de Voyage en Italie. Montaigne actually wrote that he attended “a sermon [by Andrea De Monti – he really was a censor] on the Jews on a Saturday afternoon in the Lent period of 1580 in S. Trinità de’ Monti on a Saturday afternoon. He praises the preacher’s keen reasoning, his knowledge of rabbinical literature and the languages used for it.” (Translation from the German is my own).

Popper also twice names a figure named “Mesnil” but knew nothing about him. I was able to discover that he was not an expurgator but a French lawyer at the court of Louis XIV: Gabriel-Jacques Mesnil (1717-1769). The annotation affixed by the official in charge of confiscating the assets of the Jesuits in their sites in Paris, “Paraphé au désir de l’arrêt du 5 Juillet 1763. Mesnil” (“Signed to the desire of the judgment of July 5, 1763. Mesnil”) can be read, although with difficulty, on many manuscripts (I saw some where the note was marginally and vertically inscribed). That sentence did not refer to their expurgation but simply attested that a thousand Western and Oriental (some of them in Hebrew) manuscripts had been taken away to a new destination (abroad).

In MS Oxford-Bodleian Canonici, Or. 90, I read the Italian inscription: “Jo Leone”, followed by the Latin sentence “die 13 Jan[ua]rii 1567 Heb[raeo] Leo recog[nov]it” on f. 2r. Popper found this entry in A. Neubauer, Catalogue of the Hebrew manuscripts in the Bodleian Library, I, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1886, no. 634, and assumed that Leo was a Jewish censor. But more likely, this means that a Jew named Leone owned the Oxonian manuscript that he “corrected [recognovit],” thus obeying the order of an Inquisitor who in turn reviewed this manuscript during the winter of 1567. The Inquisitor’s signature immediately follows that of Leone.

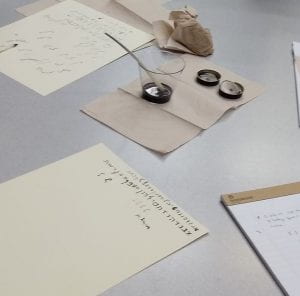

Many examples here show the interaction among written sources and scanned images of censors’ marks described at the beginning of my contribution to this blog. Bringing together these scattered sources allowed me to discover the identity of Popper’s “Jos. Parius.” In a sixteenth-century book at Columbia, Popper read “P[ate]r Jos. Franc. Pari[us] Carpi s[anct]ti officij 1604.” Instead, the correct reading is “Fr[ater] Jo[anni]s Franc[iscu]s Mala[za]pius s[anct]ti offici Vic.[ariu]s”, followed by an unreadable date. Some time ago G. Busi, Libri ebraici a Mantova. I. Le edizioni del XVI secolo nella biblioteca della comunità ebraica, Fiesole, Cadmo, 1996, no. 25, read another footprint of this censor on f. 62v of a 1552 Venetian Hebrew book: “Fr[ater] Io[anni]s Franc[iscu]s Mala[…] Carpi […] 1613”. I ordered a photo of the original page from the Teresiana Library of Mantua and so I found out that it says “fr.[ater] Io[anni]s Franc[iscu]s Malazapius Carpi s[anct]ti officij Vic.[ariu]s concedit ut […] Carpi [… …. … …] 1613”. It helped me to identify “Parius” as the Minorite Giovanni Francesco Malazappi. He was not properly a Hebrew censor but a theologian, guardian and deputy of Holy Office in Carpi (Modena). In March 1600, Malazappi compiled an inventory of books of his convent in order to to control what friars read, proving his presence in the field of the ubiquitous ecclesiastical censure.

I hope that one day a network will be created, as wide and open as possible to every scholar of involved disciplines, that will bring together databases such as Footprints and also connect them to the institutions that own the material, so that all records can be updated with current research and discoveries.

Recent Comments