Happy Anniversary, Footprints!

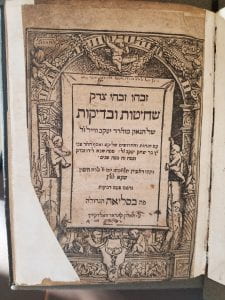

Footprints wasn’t born in a day. Before the website went live a team of planners, coders, and researchers spent years preparing. But the website made its first appearance on November 13, 2014 with the upload of a Shehitot u-vedikot (owned in Beirut in 1862).

In honor of our fifth anniversary, we decided to advance the entries on that very first item. The Shehitot u-vedikot has been of interest to me for some time now. First composed in the fifteenth century by Jacob Weil (d. ca. 1456, a student of Jacob Molin), the book outlines the laws of kosher slaughtering, and was first printed in Prague in 1533. It was something of a bestseller of the early modern period in Europe, gaining layers of commentary in subsequent publications in Krakow, Venice, Prague, Basle, Amsterdam, and beyond. A search in the bibliography of the Hebrew book for this title yields 174 results, with 130 of those books printed before the year 1800. That’s nearly an average of a printing every two years!

Opp 4o545 copy of Shehitot u-vedikot (Basle, 1611), held by the Bodleian Libraries.

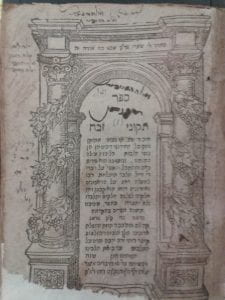

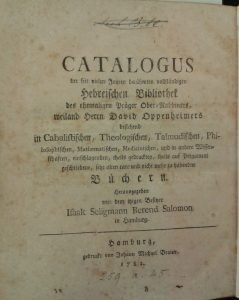

I first grew interested in these books when I came across multiple copies of them in the Oppenheim collection of the Bodleian Libraries (the full story of that collection is the subject of the recent book Prince of the Press), and found them to be rich with signatures, certificates, and even the occasional doodle, perhaps at the hand of a student whose attention wandered during his training (the trainees would have almost always have been young men). My favorite “footprint” appears in Opp. 4o 605(1), and is reproduced here (it also appears in the book, on p. 31).

Opp. 4o 605(1), copy of Sefer Tikkunei Zevah (Prague, 1604), held by the Bodleian Libraries.

Copies of Shehitot u-vedikot can be found in numerous library collections, and evidence of their historical use appears in inscriptions, the observations of Christian Hebraists, and the catalogs of modern booksellers. Tracking copies of the book offers a tantalizing example of the quantitative power of Footprints to complement, enhance, and shine a different light on our understanding of bibliography, book culture, and Jewish life more generally. Following this work we can see the power of a single author to become the authority on the topic of kosher meat production, and we can witness different centers vie for domination over the market (both economically and intellectually). We also get to see the use of books designed not for elite figures but for communal functionaries, and we can see the travel of those books beyond the centers of scholarship and publication into smaller (often rural) communities of limited resource and cultural capital. Most importantly, the rich accumulation of inscriptions in the books reveals the ongoing negotiation between the printed text and the spoken and manuscript word, that regularly intervened in and dialogued with the never-quite-canonical text.

A couple of weeks ago I uploaded information about 40 additional imprints of the work, with approximately 250 footprints accompanying those imprints, in preparation for a longer scholarly article. All of those examples were drawn from the Oppenheim collection, but I’ve been working through other collections in the US, Israel, and Europe to identify copies of the book, and am almost overwhelmed by them. And that’s a good thing. Because Footprints is all about overcoming the limits to a single individual’s capacity, and transcending that capacity through aggregated findings that are, in turn, made intelligible once more through the recombinant power of the visualization tactics of the site.

In fact, not long after those 250 footprints went live, Chaim Meiselman, Judaica Special Collections Cataloger at UPenn libraries and friend-of-Footprints discovered multiple footprints in a volume of the Shehitot u-vedikot, including one from 1719 in colonial America, leading him to wonder if this is perhaps one of the earliest to be discovered so far for the young Jewish community of North America!

In this project, as in so many others, we invite our colleagues and friends around the world to upload and share information about the historical movement of Hebrew books by recording material you may come across about the Shehitot u-vedikot (or any other Hebrew book). This incidental data from individual research will take on a new life when aggregated with others. And along the way, you may find something that advances your research as well!

So Happy Fifth Anniversary, Footprints, and thanks to all of the planners, programmers, questioners, and contributors. Looking forward to seeing what the next five years bring!

Recent Comments