by Jacquelyn Clements, Edward Fram, and Adam Shear (participants in the workshop jointly sponsored by the Fisher Library and Footprints in Toronto in June 2025.)

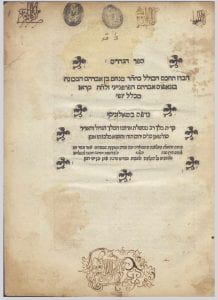

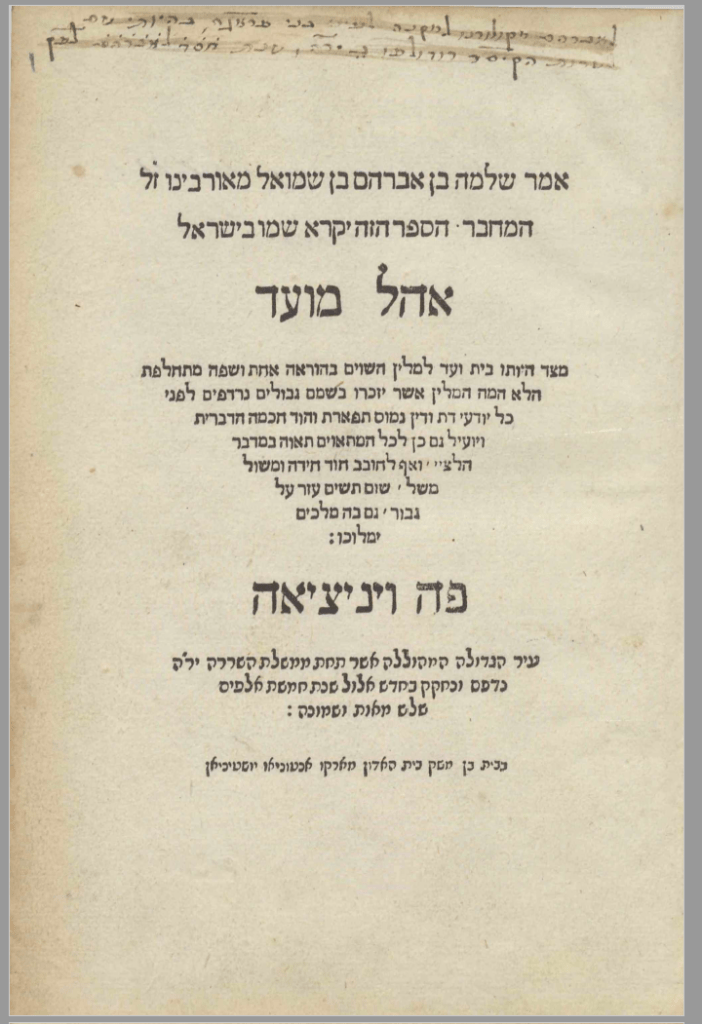

In 2024, the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library of the University of Toronto acquired at auction two books published in Venice in the 1540s on different presses but bound together. One was Sefer Yosifon, the tenth-century Byzantine chronicle of Jewish history ascribed to Joseph ben Gurion, which was printed in 1544 on the press of Johann dei Farri under the guidance of Cornelius Adelkind. The second volume, Rabbi Israel Isserlein’s Be’urim `al perush Rashi, was published at the Guistiniani press the following year. Beyond the language and place of publication, the works are only connected in that these copies were bound together sometime in the early modern period..

This was not the first printing of Sefer Yosifon, which during the medieval and early modern period was generally thought to be based on, if not an adaptation of, the work of Josephus Flavius. The book appeared in Mantua in 1476 and again in Constantinople around 1510. Since the work dealt with the Second Temple period, it interested both Jews and Christians. Sebastian Münster published the Hebrew text, an explanatory introduction in Latin, and a Latin translation with notes under the title Iospehvs Hebraicvs in Basel in 1541. The title emphasizes contemporary perceptions of the book’s authorship.

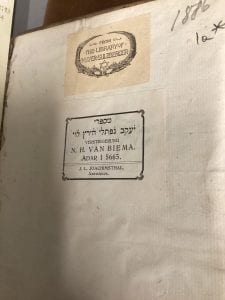

The 1544 Hebrew printing of Sefer Yosifon exists in many other collections beyond Toronto. What makes the Toronto copy special are the footprints–the ownership markings and the marginalia.

Christian Reader(s) Read Yosifon

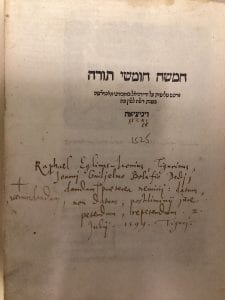

On the end sheet attached to the front cover is a note from a Jewish owner.

יונתן ב”ר שלמה הלוי קניתי זה הספר מגלח פו[פ]ן הויזן …וחצק

I, Yonatan (Jonathan) son of Mr. Solomon ha-Levi, bought this book from a galaḥ [priest or monk], (of?) the priests of Hausen… and [?].

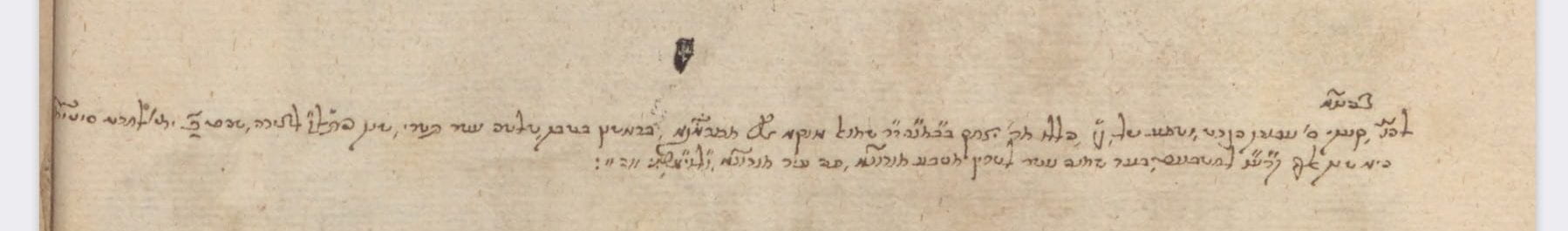

Yonatan refers to a purchase from a previous owner (“galaḥ”) but alas does not provide more information about him. The plural “priests of Hausen” (poppen hoizen) could simply be a reference to the place of origin or residence of the priestly seller of the book. Yonatan did not provide any further information about the priest (or priests), however, the transfer of the book from Christian to Jewish hands was more than simply a matter of ownership. Previous Christian owners carefully studied this copy of Yosifon. (We surmise multiple Christian readers, perhaps in an institutional setting, due to different hands.) They added copious notes as they worked their way through the text with several Hebrew, Latin, and Greek texts in front of them (or in mind). The simplicity of some notations, such as those completing the ultimate letter of Hebrew words marked with an abbreviation mark (‘), should not lull contemporary readers into thinking that Hebrew was an almost insurmountable challenge for Christian readers. The Christian readers who annotated this text were meticulous, and even minutiae were noted. The Hebrew citations were written in clear square letters. The lack of any Hebrew semi-cursive letters almost certainly suggests Christian users (and most likely not converts from Judaism). Our Christian readers often connected their marginalia to the text using crosses. The annotators also used Latin abbreviations throughout to highlight and explicate key Hebrew phrases and to compare them with other editions of the text.

The transfer of ownership of this book, noted on the endpaper, brought Christian scholarship right into Jewish homes. While it is uncertain whether later Jewish owners appreciated or used this Christian learning, anyone who opened this volume had to be struck by the interest Christians took in this Hebrew book and the time and energy they devoted to glossing it.

The marginalia are worthy of scrutiny and further study. At least one Christian reader was not pleased with what he saw before him. The pagination of the first two folios has been crossed out. The Hebrew letter gimel, noting folio three, has been struck out and replaced with a square letter alef, re-paginating the book. Each Hebrew chapter number heading (e.g., pereq shelishi) has been replaced with the Latin Cap. followed by an Arabic numeral for the chapter number (e.g., Cap. 5). Readers struggled with the numbering, and at least one reader revised the Latin chapter division that had already been inserted. What was once Cap. 6 later became Cap. 10. New headings were also introduced, with Cap. 4 dividing what in the Hebrew text is chapter 3. The Hebrew running headers intended to remind readers of their place in the book were stricken to reflect these changes.

Christian readers tried to align this copy of the 1544 Hebrew text of Yosifon with Münster’s 1541 Hebrew text and translation. This posed an immediate problem because the 1544 Hebrew text includes material not found in Münster’s Hebrew text. The 1544 edition begins with Adam and his progeny (fol. 1a). Münster’s edition began with Darius the Mede and Cyrus the Great (Münster’s Hebrew text is not paginated). Münster mostly followed the first Hebrew edition printed in Mantua in 1476, but omitted the first three chapters (for a brief description of the different editions of the text, see The Jewish Encyclopedia, s.v. Joseph ben Gurion). Lining up the early sections of the two versions was difficult. Things seem to have become clearer for the reader at the beginning of the Purim story that appears in chapter four of the 1544 Yosifon (fol. 15a). There a Christian reader crossed out Chapter 4 in the Hebrew (pereq revi`i) and wrote Liber secundi, Lib. 2. Cap. i., corresponding to Münster’s Book Two, Chapter 1, beginning on page 17 of his Latin translation. Differences in the texts continued to plague the redivision of the Venice edition, but the pattern was set.

The Venice text was read closely with Münster’s Hebrew, for there are numerous marginal notations to “Müns.” Some are relatively simple. For example, on fol. 11b, the reader noted: “Pro hoc Münster legit: וַיִיקַץ,” where the word ויקם appeared in the 1544 Hebrew text. Missing texts were pointed out (Defúnt haec), based on Münster. Generally, readers annotated the Venice copy in the margins, sometimes at great length. In one case (fol. 88), the notations were so lengthy that there was a need to continue them on a separate sheet bound into the volume after Isserlein’s work (pag. i). However, the page appears to have been cropped, indicating that the reader worked on this before it was inserted into the volume. The addition of this page and 65 blank additional folios, some of which have a single-headed eagle watermark, suggests that the Christian owner(s) who ordered the binding were in German lands and expected that readers would continue to comment on and/or gloss these works.

Christian readers of the Fisher Library copy of Yosifon went beyond Sebastian Münster’s text and translation. There are marginal references to biblical texts and a cross-reference to the Book of John 9.7 (fol. 130a) to help readers understand the phrase, “the waters of Shiloah.” “R. Salo.” (fol. 2a), presumably the important eleventh-century Jewish exegete Rashi, also appears. Indeed, the Hebrew רש”י is found in notes on fols. 2b, 13a, and 29a, the latter two making specific reference to Rashi’s comments on verses in Daniel. Jewish readers not in conversation with Christian scholars might have been surprised, if not shocked, to find that Christians not only knew of the important eleventh-century Jewish exegete but read him carefully. This interest in Rashi may help explain how Isserlein’s book on Rashi’s biblical commentary came to be bound with Yosifon. There are references to other works such as Isaac Vossii’s de [vera] ætate mundi, which was printed in 1659 (on fol. 18a), perhaps in a different hand than most notes in the volume. There is also a reference to Johannes Buxtorf’s De Synagoga Judaica (fol. 104b), perhaps in yet a different hand.

Christian readers’ annotations in Sefer Yosifon, 1544, Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto, B14-01386

Münster was not the only translation consulted. David Kyberus’s Historia belli Judaici, a Latin translation of Josephus’s work, is also referenced (fol. 73a). (Kyberus’ Latin translation included the chapters from the Hebrew that were omitted by Münster.) There is also a cross-reference to a “ver. Germ. pag. 332” (fol. 141b), presumably a German translation from the Latin version of Josephus. Such translations appeared in print already in the first half of the sixteenth century. Specific passages from the Greek and Latin versions of Josephus are referenced in a marginal note on folio 104b. The annotation includes a Greek word and a reference to a section of Lucian’s De morte Peregrini.

Christian annotation of the Toronto Yosifon peters out after about 20 folios, although the marking of chapters according to Münster’s volume continued. However, in the third book (fol. 30b), someone returned to an intensive reading of the text and continued to do so until folio 92. The combined work of these Christian scholars provides an example of how Christian Hebraists read and compared texts, while the “footprints” in this copy show how a Hebrew text moved into the Christian world and then returned to the Jewish community laden with different frames of reference.

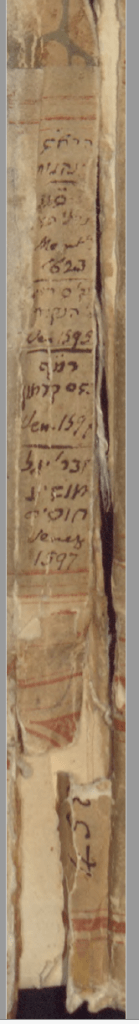

When and Where?

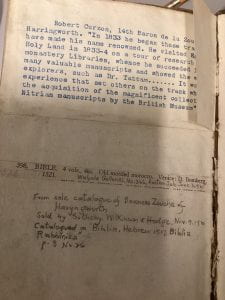

Unfortunately, the first four folios of the Fisher Library’s copy of Sefer Yosifon, as well as the last four folios of Isserlein’s supercommentary on Rashi, are missing and have been carefully photo-reproduced from other copies by a recent owner of the volume. Thus, any ownership marks on the title page of Yosifon are lost to us. But the binding and some of the annotations offer us some suggestions.

A page at the front of the bound volume includes notes by one of the Christian readers on the authorship of Yosifon and, not surprisingly, a discussion of the so-called “Testimoniam Flavium,” a statement about Jesus attributed to Josephus and used by Christian polemicists in the Middle Ages as evidence of first-century Jewish recognition of Christ. One of the texts cited is a work by Johannes Andreas Bose (Bosius) (1626-1674) as “Exercitat. in periocham Fl. Josephis de Jesu Christo. Cap. 2, s[ection] 46.” Our annotator gives no date for this work, which was first published in Jena in 1673. Another note on this page refers to Stephanus (or Étienne) le Moyne (1624-1689)’s Varia Sacra, volume 1, with the place (Leiden) and date of publication (1685) given. These references suggest that the work was still in Christian hands in the last decades of the seventeenth century.

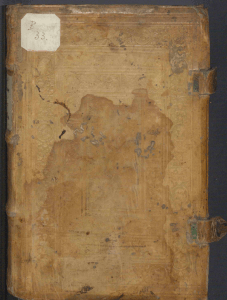

It is not clear when the two books were bound together. The binding is in a typical sixteenth- or seventeenth-century German design with names, images, and floral decorations embossed on the front and back leather covers. Clearly visible are names and images of Erasmus of Rotterdam, Martin Luther, as well as Lucretia (about to thrust a dagger into her heart), Justice, and Philology.

The image of Luther, along with the predominance of Protestant theological works quoted in the annotations, makes it almost certain that the book was not just in Christian hands but in Lutheran (or possibly Reformed) hands. Our Jewish purchaser, Yonatan ha-Levi, uses a term “galaḥ” which derives from the shaved heads of monks, but it seems almost certain that the Christian cleric who sold him the book was not a monk.

As for geography, there are several places called “Hausen” in German lands, but our best guess is that it the Hausen that was on the outskirts of Frankfurt am Main as a later owner of the book, Elias Sussels, signed his name in both Hebrew and German and identified himself as living in Frankfurt. The Frankfurt book fair included not only the sale of newly printed books but a lively trade in used books and would have been a natural place for a Lutheran priest to sell a Hebrew book to a Jew. Why our Lutheran owner no longer needed or wanted the book is not clear.

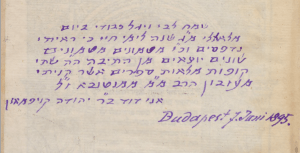

When did this transaction take place and when did the book pass from the hands of Yonatan bar Shlomo Halevi to Elias Sussel? Unfortunately, here too we can only make educated guesses. The earliest Yonatan could have bought the book was 1685 (the date of the work by Le Moyne cited in the notes of one of the Christian readers). Elias Sussel does not tell us he purchased the book from Yonatan but from someone named Joseph for certain number of batzen.. With at least one owner between Yonatan and Elias and with Elias’s interest in copying his name in Latin letters, we might place Elias in the late eighteenth century or early nineteenth century. However, we have not been able to find information about him in sources about Frankfurt Jews, such as Shlomo Ettlinger’s Ele toldot, a genealogical record of Frankfurt Jewry from the sixteenth until the first decades of the nineteenth century. We would be grateful for any information about Elias or the others who owned the book and will be pleased to update the footprints in the database accordingly.

Just as it seems that multiple Christian readers were interested in reading and annotating the book, it seems to have also interested multiple Jewish readers. An inscription below this tells us that Yoel ben Moses Hazan bought the book from Elias and then resold it to him later.

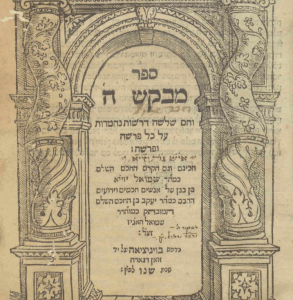

What about the second book bound with the Yosifon, Israel Isserlein’s Beurim `al perush Rashi? Isserlein was a prominent mid-fifteenth century Ashkenazic rabbi known both for his halakhic works and this supercommentary on Rashi, a sub-genre which engendered great interest through the sixteenth century. This Venice, 1545 printing was the second edition of the work, the first being that produced by Daniel Bomberg in Venice in 1519. The book was subsequently reprinted in Riva del Garda in 1562 and, again, as part of an edition of Rashi’s commentary in Venice (Zanetti) in 1566. While Christian readers were often interested in Rashi and other medieval rabbinic biblical commentators as a “telephone line” to the original Old Testament (in Beryl Smalley’s memorable phrasing), it does not seem that either the Christian readers of Yosifon or the later Jewish owners of the volume ultimately had much interest in Isserlein. The work is devoid of marginalia. The title page of the Fisher copy contains 3 inscriptions in Hebrew, none giving us much information about ownership or the relationship to the other book in the volume. One merely copies word for word the subtitle of the book and the authorship information. The second would be most promising as it appears to be the name of an owner but is rubbed out. The third note mentions the purchase and a price but no name:

קניתי זה הספר בעד [ה] ב”ץ

“I purchased this book for 5? batzen.”

One hint of a Christian hand lies in the hand-written Arabic numerals for the date of publication underneath the Hebrew year on the title page, “1544.” This (Christian?) date-noter shows a relatively sophisticated understanding of the Hebrew year as the Hebrew date on the title page is 305 “according to the lesser reckoning,” a year that began in fall 1544 and continued through the end of summer 1545. The title page does not tell us when the printing took place during that year, and there is no printer’s colophon, which often gives a more precise date for the completion of the printing. So there is no way to really know whether the work was produced in late 1544 or early 1545. Perhaps our reader was also trying to find a connection through a common year of printing for the two books he found bound together?

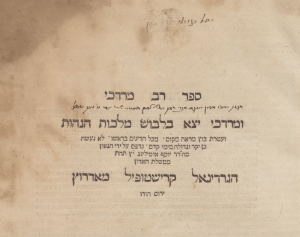

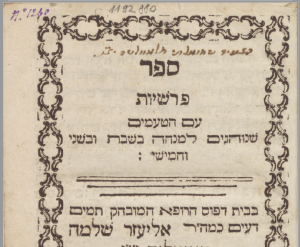

title page of Isaac Isserlein, Beurim, Venice, 1544/45, Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto B14-01386

There is much we don’t know about the history of this particular book (or more precisely this bound volume with copies of two imprints) and there is much more research that might be done here—on the owners of the books, for example, or a more in-depth analysis of the marginalia and annotations of the Christian readers. But attention to provenance and book use allows us to add this Fisher Library book to the relatively short list of book copies owned by Christians and then acquired by Jewish owners. Historians of the book have noted the many ways in which Jewish books and manuscripts have entered Christian collections in both early modern Europe and in the formation of major modern library collections from the nineteenth century on. Much remains to be discovered about movement in a different direction, from Christian hands to Jewish hands.

Recent Comments