Many thanks to Eli Genauer for agreeing to write a blog post on one of his books represented in Footprints. The book discussed is a Bible – the last on the list of Bibles found in the database (click the + under the title of the book to see all Footprints for this and other books).

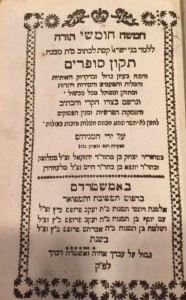

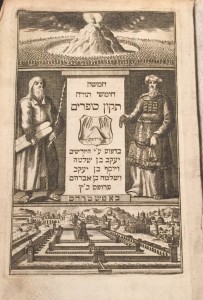

Our book was published in 1797 in Amsterdam by the Proops family, which printed books from the late 17th century to the mid 19th century.

This particular volume is Sefer Shemot of the Five Books of Moses. It features a beautiful woodcut of Moses receiving the Torah, along with Moses and Aaron, and a rendering of the Holy Temple.

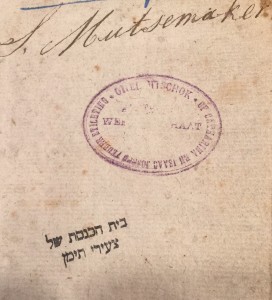

There are three owners’ marks in this book, described below.

The first clearly identified owner was Simon Mutsemaker (Amsterdam, 1766-1827) who boldly signed his name on the book’s front flyleaf. We can assume he bought this volume as a part of a set of all five books of the Pentateuch, but only this one volume remains.

The next ownership stamp is not of an individual, but of an old age home in Amsterdam that housed a synagogue within it.

Around the edges of the circle, the stamp reads “Ohel Yitschok *Of Catharina En Isaac Joseph Fedder Stichting* ” (Ohel Yitzchok of the Catharine and Isaac Joseph Fedder Foundation). This indicates that the book belonged to the synagogue which was part of the old aged home established in the name of Catherine and Isaac Joseph Fedder. In the center of the stamp is the street on which the old age home was located, Weesperstraat, in Amsterdam (The Netherlands).

We know a bit about this Amsterdam institution and about its founding benefactors:

On October 18, 1829 Isaac Joseph Vedder was born on Rapenburgerstraat. He married Catherine De Groot in 1855. In 1874 the couple moved to Weesperstraat 41.

Isaac made a fortune in the diamond business, but continued to maintain a very frugal lifestyle. When Catharine died in 1890, Isaac established a foundation in both of their names whose goal was “to provide careful nursing, nutrition and care in the widest sense for men, whether healthy or sick”. Additionally “the building should be decorated with a synagogue.” Also included was the stipulation that there must always be at least 10 male residents of the home, so that there would always be a Minyan and services could be held. “The men must be of impeccable good character, religious minded and confess the Ashkenazi Jewish religion .” [emphasis added]

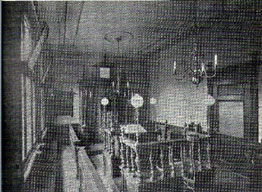

The property next to Weesperstraat 41 , number 43 , was purchased and the old men’s house was made from these two addresses. The synagogue was on the first floor, on the left side of the building. It was a small synagogue, only 7.50 x 4.20 meters, but an impressive beauty. On the east side was an Aron Ha-Kodesh – the holy ark. On the other three sides were the seats, at most 30.

During World War II, all the residents in the home were killed by the Nazis. The building itself survived the early ravages of the war. However, in the winter of starvation (1944-45), precious wood was salvaged from the property to use for kindling. After the war the building had to be demolished.

During World War II, all the residents in the home were killed by the Nazis. The building itself survived the early ravages of the war. However, in the winter of starvation (1944-45), precious wood was salvaged from the property to use for kindling. After the war the building had to be demolished.

So what happened to this precious book?

Aside from trying to physically destroy the Jewish people, the Nazis also systematically pillaged the treasures belonging to the Jewish community that bore witness to Jewish creativity and scholarship. Some of these treasures they planned to keep for themselves, but others were to be consigned to landfills or burned. After the war, there was a complex question of what to do with the surviving Jewish treasures, including many books, whose owner s were no longer alive. A tremendous effort was made to find appropriate homes for the multitude of now-ownerless books that had been confiscated. Much of that work was performed by the Jewish Cultural Reconstruction project. Among the many places these books were sent was the newly established State of Israel.

s were no longer alive. A tremendous effort was made to find appropriate homes for the multitude of now-ownerless books that had been confiscated. Much of that work was performed by the Jewish Cultural Reconstruction project. Among the many places these books were sent was the newly established State of Israel.

Although none of the residents of this home for aged men survived the war, their book did, and is a testimony to the home’s existence. Somehow, possibly through more informal means, it found its way to Israel, to a place that may have seemed quite unfamiliar to those elderly Jews of Ashkenazic descent.

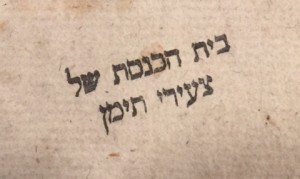

The book’s next owner was the Beit Ha-kenesset shel tse’ire Teman, a synagogue and cultural center in Rehovot, Israel that (to this day) serves the Yemenite community and strives to keep the form of prayer and traditions of that ancient community alive. Note the term “tse’ire,” which means “young people.”

The book’s next owner was the Beit Ha-kenesset shel tse’ire Teman, a synagogue and cultural center in Rehovot, Israel that (to this day) serves the Yemenite community and strives to keep the form of prayer and traditions of that ancient community alive. Note the term “tse’ire,” which means “young people.”

There are, of course quite a few differences between Simon Mutsemaker, Catharina and Isaac Joseph Vetter, and the elderly Ashkenazic residents of the old age home on Weesperstraat 41 on the one hand, and those “young people” who prayed at the Yemenite synagogue in Rehovot on the other. They looked different, their Nusah of prayer was different and many of their Minhagim were different. But this book that united them was more important than all of that. It was a book of the Torah, the Sefer Shemot, which all these people believed to be the defining part of their religious heritage.

Recent Comments