Molly Pocrass has been working with Columbia’s Footprints project for about 10 months. “I can honestly say that before then, I didn’t really think about the history of the books I read or even handled. That has changed now, due to the materials I have been privileged to catalog and my work tracing where they’ve been before.”

Molly Pocrass has been cataloging sixteenth-century Hebrew books printed in Venice that are part of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America’s (JTS) collection of rare Jewish books. While cataloging these books, she has been entering records into the database Footprints: Jewish Books through Time and Place under a grant from the Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation. Venice in the sixteenth century was the leading center of the Hebrew printing industry, home to Christian publishers working with Jews, Christians, and converts from Judaism to Christianity engaged in editing, proofreading, typesetting, and printing the full range of Hebrew literature. Their printshops were also places where those from northern Italy mingled with migrants from across Europe and the Middle East. The early sixteenth-century printer Daniel Bomberg, a Catholic who had relocated from Antwerp to Venice, was responsible for printing the Rabbinic Bible and the first full set of the Babylonian Talmud, all with multiple commentaries on a page. Other major sixteenth-century Venetian printers, including Cornelius Adelkind, Alvise Bragadin, and Giovanni di Gara, produced bibles, collections of midrash, halakhic texts, siddurim, and works of philosophy, grammar, kabbalah, ethics, and more.

The collection at JTS is a testament to the many Jews of the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century who had both the passion for collecting Hebrew books and the foresight to gift them to an institution where they could be used by others. While their donations to libraries like JTS were expressions of their Jewish identity and philanthropic interests, they also made their book collections available to generations of scholars engaged in research. Cyrus Adler, Mortimer L. Schiff, Mayer Sulzberger, Elkan Nathan Adler, and Hyman G. Enelow were some of the more well-known donors at the time. In addition, many of these Jewish philanthropists funded the purchase of Jewish books from both Jews and non-Jews in the thriving antiquarian book trade in places like New York, Philadelphia, and London.

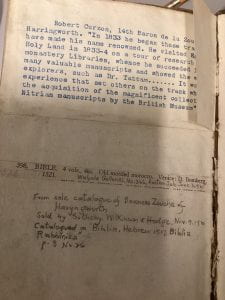

Tracing the acquisitions by JTS of many of the Venetian books in particular yielded many fascinating stories, as Ms. Pocrass reports. She was drawn to a set of the Tanakh printed by Daniel Bomberg in 1521 and purchased in Padua in 1832 by Robert Curzon, the 14th Baron Zouche (1810-1873), a celebrated world traveler famous for his travels in the eastern Mediterranean (which he described in an 1849 publication entitled Visit to the Monasteries in the Levant).

Curzon’s extensive manuscript collection is now in the British Library, but his printed books are dispersed. Little is known about the travels of this particular copy before 1832. Did this Tanakh travel far and then return to the Veneto region or did it spend its first 300 years in close range of where it was printed? Did Curzon acquire it in Italy or Palestine or elsewhere? Its twentieth-century history is better known. In time, this book was inherited by his daughter Darea Curzon (16th Baroness Zouche) and sold by her estate in 1920. Finding the signature of a woman, let alone a baroness, in a Hebrew book points to the active role that women played in book collecting in the early 20th century. The book was sold again at auction by Walpole Galleries in New York just five years later, and was purchased there by Newark department store magnate Louis Bamberger (1855-1944) on June 3, 1925. Two days later, he presented it to JTS.

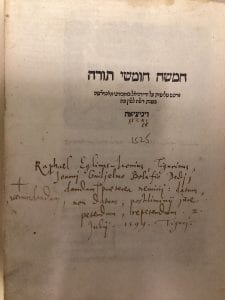

As in the rest of the Footprints database, evidence such as signatures, bookplates, and library accession numbers in other books reveal more about the early modern exchanges of books. Within them we find information about ownership of Judaica and Hebraica that reveal cross-cultural exchanges and investment. One example is the sale of a 1525 Pentateuch from one priest to another (Johannes Bolafius to Raphael Eglin) in Zurich in 1599. Despite a gap in our knowledge of the pathway of this book that stretches from 1599 to the late nineteenth century in Philadelphia, when Meyer Sulzberger added the book to his large library. He then donated it to JTS.

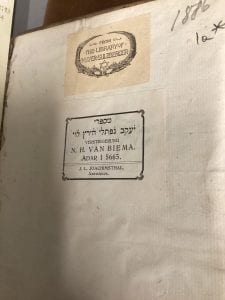

Although the bulk of Sulzberger’s collection was given to JTS in 1904, his collecting activities did not cease, and he continued to present books to JTS. Two books, Avodat Ha-levi (Venice, 1546) and Temunot Tahanot (Venice, 1546), bear bookplates in Hebrew and Dutch indicating that books owned by Yaakov Naphtali Hirts Levi (Naphtali Hertz van Biema in Dutch) were auctioned by J.L. Joachimsthal in Adar 5665 (February 1905). Mayer Sulzberger’s familiar bookplate also appears in these books.

Hebrew books in Italy at the end of the sixteenth century and in the seventeenth century were subject to review and expurgation by censors employed by the Catholic Church, some of whom were born Jewish. Pocrass came across a few of the more notable ones such as Giovanni Domenico Carretto, Camillo Jagel, Domenico Irosolimitano, and others who were active at this time. Books with the markings of these and other censors can tell us–even in the absence of ownership notations–where the books were at a given point in history. They also connect us to the censors themselves, prompting us to think about a point in Jewish history when the church controlled what it wanted Jews to read and not read.

As a result of the grant from Delmas Foundation, hundreds of uncatalogued early Venetian books have not only been cataloged for JTS and made available, but also information found within these books about their prior owners has been added to Footprints. Users of the Footprints database now have more usable data regarding Jewish books printed in other parts of the globe that can be aggregated and compared. As Pocrass notes, her work in tracking these myriad histories “has brought these books to life in ways I could not have imagined before I began this project.”

Recent Comments