This Friday, while passing through China coming back from the Japan trip, I ran into an interesting article on the Global Times about how Chinese students in South Korea where being affected after the Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) anti-missile system was deployed. As you may know the US designed an anti-missile system to protect South Korea and Japan from possible attacks from North Korea, which China has seen as a threat to its own military operations. This of course is starting to have implications in the relationship between China and South Korea, but probably no one thought about the effect this would have on Chinese students taking high-education studies at South Korea.

The university students interviewed for the Global Times’ article mentioned they are – for the first time – not feeling welcome in their neighbor country, and even worried about their personal safety. They feel rejected when South Korean people spot they are from China and they have experienced some disrespectful manners from random people in the last weeks. Students are afraid South Korean teachers with a strong opinion about the THAAD will also take a position against them affecting their performance and study in school. This is a situation that was not happening a year or even some months ago.

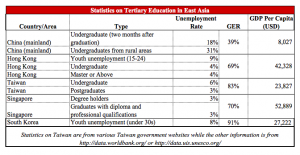

Currently, around 60% of overseas students in South Korea come from China, but will this situation play against this numbers? As stated in the paper ‘Political and Economic Impacts on Chinese students’ return’, China has been experiencing a brain drain in the last years as having many Chinese students that decide to stay in the country where they are studying instead of returning to their home country. The paper analyzes the possible factors that contribute to students deciding not to go back, and one of the most important ones where the economic situation of the country they are studying (mainly focused in the US, but applicable to other countries as well), and the stimulating policy held by China to return home. Taking into account these factors, it cannot be totally predictable what will happen with Chinese students in South Korea, as this situation may or may not have a strong effect on student mobility.

Moreover, what is also interesting from the Global Times article, is that the students interviewed mention how Chinese people is starting to perceive them negatively as students living in South Korea. Since the THAAD situation they are labeled by many Chinese people as ‘unpatriotic’, almost as if they were playing as part of ‘the enemy’. So it is not only they are feeling unwelcome in their study country, but they are also feeling outsiders in their own country. In line with this perspective, the paper by Wu & Shao, discuss the difficulty Chinese students that have studied abroad have when going back to China. It is mentioned as one of the most painful experiences as trying to adapt again to a country that has probably changed in the years the young Chinese has been living abroad. China is a country that is constantly changing and developing, and many factors become uncertain for young people trying to reinsert in the Chinese society and market. Also, considering the China – South Korea relation, getting a degree from a country like South Korea might be seen as negative and have an impact on the students’ future career and job hunting when graduated. It might be only the image from having studied in the country, but also if the relationship continues to take a negative path, South Korean companies might start to exit the Chinese market reducing the possibilities of these students to be hired by a South Korean company in their home country, affecting their future employment.

Nevertheless, a consultant at the Weilan South Korea study agency mentions that so far, ‘they haven’t seen a decline in students applying for South Korean universities’, and compares it to that even though the relationship between the US and China is not the greatest one, still Chinese students choose to study in the US. But even if the numbers currently are not telling much, the fact is the feeling of Chinese students is still there, they have now started to worry about politics like never before because they are being directly impacted.

Should this be a factor worth considering for South Korean universities in the following years? Maybe it becomes better for China as to avoid brain drain from Chinese students going abroad? How can the relationship between two countries really affect the higher education mobility between them? There are in fact some important social consequences from the countries’ relationship that are starting to get noticed. This does not pretend to be a statement, but more to stir the discussion about other aspects that sometimes are not considered in the higher education mobility equation.

Sources:

- The Global Times (English version). Volume 8. No.2249. Friday, March 24, 2017

- Wu, Harry & Shao, Bin. ‘Political and Economic Impacts on Chinese students’ return’. Journal of International Business and Cultural Studies. Volume 9. December 2014. http://www.aabri.com/manuscripts/141963.pdf