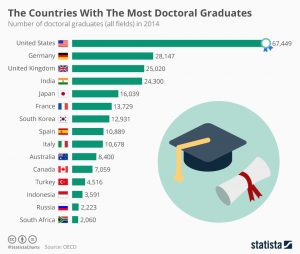

A recurring question in our course is who the next leader in higher education (in Asia) will be. The World Economic Forum recently released an article on countries with the most doctoral graduates across the world. Unsurprisingly, the current leader in higher education – the US – leaves the rest of the world behind by a wide margin.

Based on this, do you think we should add the number of PHDs a country is producing to our discussion on who the next leader in higher education will be? While you may find shortcomings of using this approach based on our country-level class discussions, do you think it will be useful in combination with other indicators? If yes, which ones?

In your discussion, you can consider that according to this measure, India, followed by Japan and South Korea, are most likely to emerge as leaders.

Read the full article, which includes details on the source countries of PHDs here: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2017/02/countries-with-most-doctoral-graduates/

Image source – https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2017/02/countries-with-most-doctoral-graduates/

Like many others, I share the sentiment that Ph.D’s should be accounted for, but only in regards to their relevance and productivity. Furthermore, as others have touched on, there are many professions where a Ph.D is not the natural terminal degree. Engineering is a good example. Most engineers stop at a master’s degree (as Howard in The Big Bang Theory is always poked fun of about, haha). Also, technically a MPA/MIA degree is generally considered a terminal degree. Of course, these generalities vary depending on country, position within a particular profession, and many other factors. Yet, perhaps the typical terminal degree should be considered on the same level as a Ph.D in this circumstance.

Thank you for sharing this article. I think it is also important to consider the fact that not all universities in non-US countries fund their PhD students in terms of a stipend or allowance, and so naturally there are far fewer doctoral students in those countries as compared to the US (which generally provides at least partial funding for their students). The UK for instance, offers grants to postgraduate students via respective research councils that correspond to their academic disciplines. However, the fact remains that not all postgraduate students in the UK are granted funding, unlike the case in the US.

More information on postgraduate funding can be found here: http://www.ahrc.ac.uk/documents/guides/research-funding-guide/

https://www.epsrc.ac.uk/funding/howtoapply/fundingguide/

In my opinion, the number of PhD is an important factor when we evaluate the impact of PhD, but at the same time, the number of PhD per population is also an essential indicator. If we use this indicator, the ranking changes a lot. Additionally, the PhD ratio over the number of researchers in companies is also an important factor since it greatly affects a country’s productivity.

It is an interesting indicator. However we have to recall that each country has its own purpose of high education. Many country in the world are during the phases that they need STEM students to promote their productivity and technology based improvement. For those counties in need of talents in those industry, they do not really need a PHD to be effectively benefit the society. Being practical is more relevant. So students in those counties do not really consider to pursue a PHD.

Thanks for bringing this article, Wajehha. I wonder if they missed the Chinese data or there is any reason behind they didn’t include China. Actually, according to the National Bureau of Statistics, China produces more than 50,000 Ph.D every year and recruited more than 70,000. https://gss0.baidu.com/-4o3dSag_xI4khGko9WTAnF6hhy/zhidao/pic/item/72f082025aafa40f9ffcee6da364034f78f01943.jpg

The first line is the number of recruitment, the second line is the number of graduation. I didn’t find the English version.

Although China may have a high number of Ph.D graduates, I highly agreed Dai’s opinion that the real important question is the quality and their contributions to the society. In China, Ph.D graduates also face difficulties to find jobs.

Thanks for the source. WEF has always been a powerhouse source in economics and development news, but to answer your question I don’t think we should add the # of PhDs awarded by each country as a criteria, especially in relation to economic growth as the WEF article argued. Yes, the US has been the leader in producing PhDs, but that has not guaranteed their leading position in world economy compared to the fast-rising China and India who lagged way behind in PhD numbers (China was not even on the list). I think the fairest way to judge PhD education is not the number of PhDs produced, but what these graduates do after they get their PhDs, and it does not seem that all of them are productively employed. The reality of the tenure system in academia make it hard to open new jobs every year while the number of PhDs increase, thus unless you have a PhD in STEM where it’s easier to transition into business, it’s much harder for humanities and arts PhD to find a job in their field. This is a rather old article from the Economist (http://www.economist.com/node/17723223) but I think their analysis regarding PhD overproduction in the US is still relevant.

Hi thanks for the sharing the article! Briefly, I share the same sentiments as the others commentators. The number of PhDs produced could for instance, indeed be an indicator of the attractiveness of the country’s universities to foreign students (if we have the breakdown of domestic vs. foreign PhD students), but as the other commentators have pointed out, quantity does not necessarily mean quality (for instance, the standards could be less strict).