Miryam Gordon is a student in Johns’ Hopkins’ Museum Studies program. Miryam completed a digital curation internship, during which she worked on all aspects of Footprints. She has generously shared her final thoughts and feedback on the project, and has allowed us to reproduce a portion of it here.

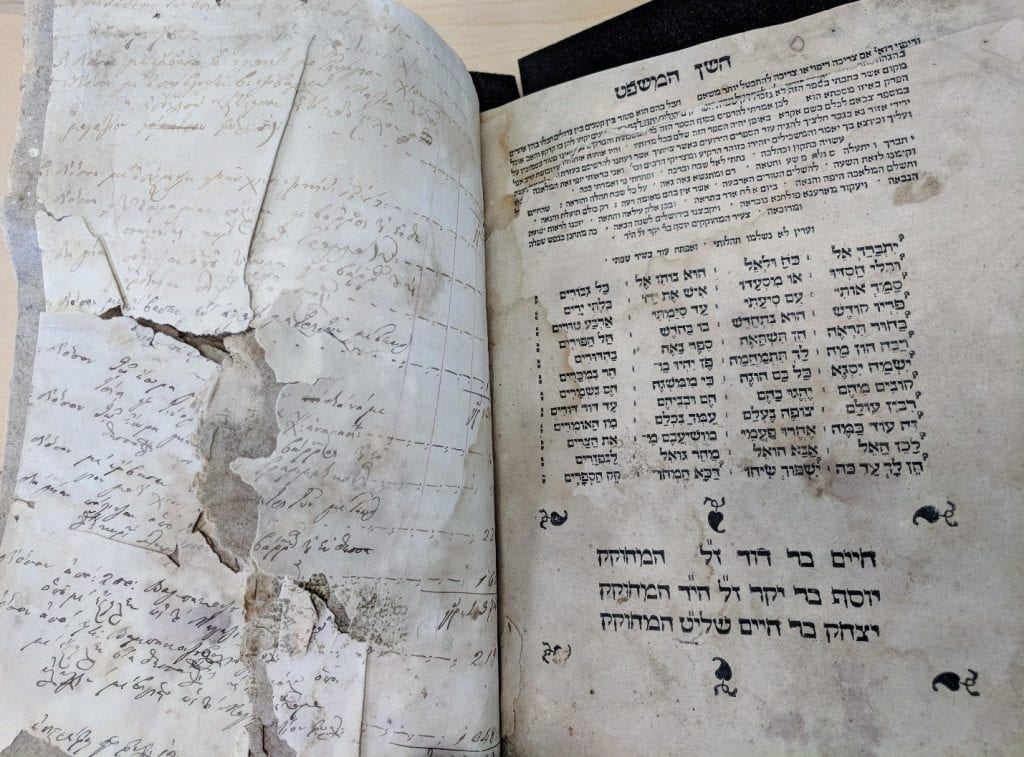

Collaboration is a necessary ingredient for effective scholarship and creation of new knowledge. While collaboration has long been in use, the innovation behind Footprints is the digital aggregation of multiple bodies of data regarding Jewish book circulation into one location. Libraries and information that have been scattered around the world are being virtually reunited through the project. Footprints has managed to become an effective model due to its community approach, transparency, accessibility, and flexibility. While the project may not yet be perfect in all areas, it had been set up with systems and policies in place that are causing it to be effective in each of these areas.

- Building an Engaged Community

Success in Digital Humanities comes from an understanding that scholarship is a social undertaking. Current technological advances can be used to “share and exchange skillsets, continuous change, and collective decision making” (Chesner, Lehman, Shear, & Teplitsky, 2018). From its founding, Footprints has been a collaboration between scholars at Jewish Theological Seminary, Columbia University, University of Pittsburgh, and Stony Brook University. The advisory board consists of historians, scholars, librarians, and other experts from institutions such as Queens College, Oxford University, University of Pennsylvania, Princeton University, Jewish Historical Museum, and the National Library of Israel (Footprints, n.d., “Credits”). In addition to individuals from these institutions, even before the site’s creation the directors had many conversations with other experts to gain their feedback and even conducted beta testing to ensure that everything was working appropriately. Interest in Footprints has risen due to conversations at conferences and on social media. As interested parties hear about Footprints and its purpose, they recognize its value in making previously hidden collections widely accessible.

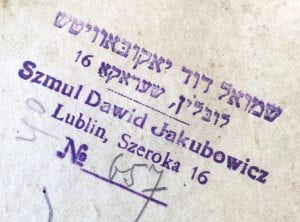

Footprints’ success relies on a vast network of invested contributors. If only those that were initially involved were the ones contributing, the database would not go anywhere. It relies on a community of users to get to a truly valuable critical mass. Footprints has an increasingly growing list of institutions and scholars around the world that are working to add data to the site. Its directors encourage colleagues and scholars to add information, as well as encouraging professors to teach using the repository to build continued interest and involvement (Lehman, 2016). Footprints is working with libraries and institutions from all over the world to capture and upload information from their books and other resources to the site. Examples include: Leo Baeck Institute, Russian State Library, Washington University, Archbishop Marsh’s Library, Library at the Katz Center for Advanced Jewish Studies at University of Pennsylvania, Yeshiva University Library, and the Material Evidence in Incunabula Project at Oxford. There are over fifteen individual scholars and researchers listed on Footprints’ site as having worked on the project in some capacity (Footprints, n.d., “Credits”). Contributors to the project have been varied and located across the world.

Without encouraging and supporting these users and contributors, Footprints would not have seen the success that it has to this point. However, the project directors still need to work on creating a centralized method of communication between contributors. While many individuals and institutions are actively working on the project, they would benefit from a centralized place to communicate and share insights. Footprints’ blog and twitter feed are places where this does occur, but that is controlled exclusively by the project’s directors. Some user-generated content would encourage said individuals and give them a stake in the process of building the repository. Perhaps a discussion board or a comments section under the records would be helpful in this down the line. (Ed. note: We do have a Google Group for Footprints contributors, but we could do better in promoting and encouraging its use)

- Transparency

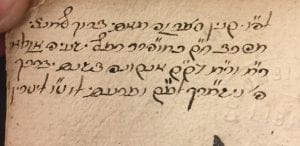

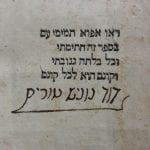

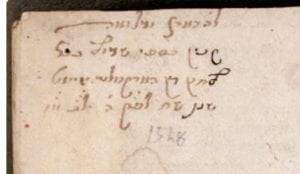

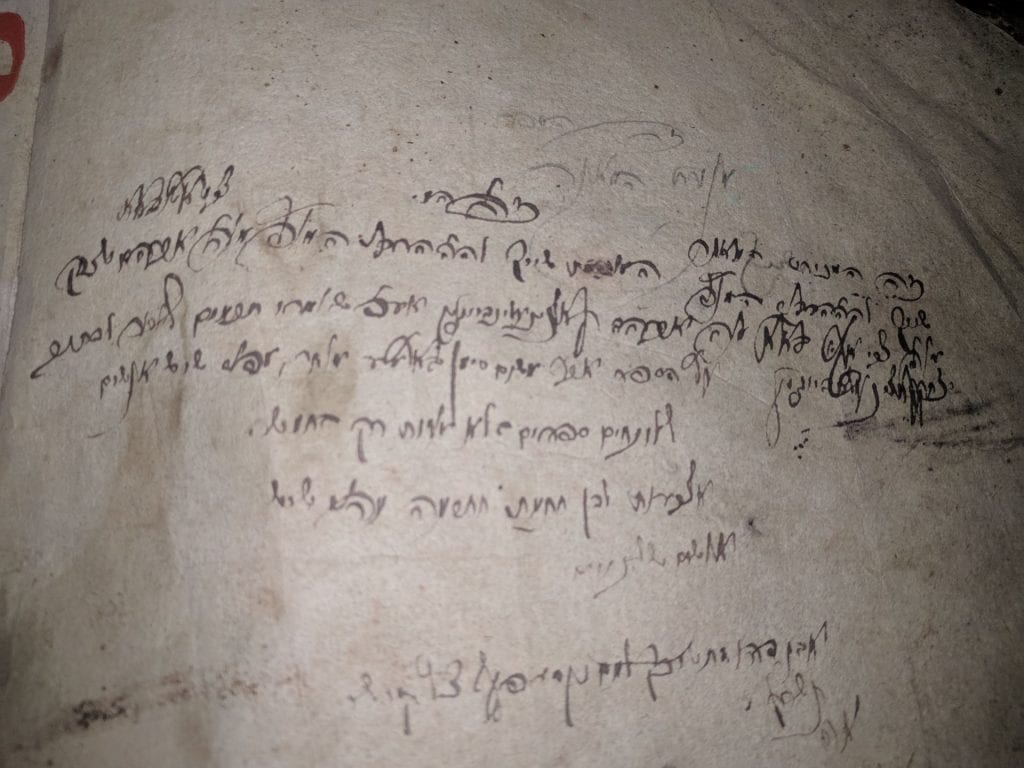

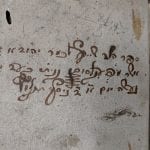

Footprints is touted as a scholarly project and so it is essential for it to be transparent to be trusted and taken seriously. Each footprint record cites the evidence from which it is derived. If users wanted to, they could easily view the source from which the contributor determined that information (Footprints, n.d., “How to Enter a Footprint”). To address those that are skeptical about the idea of crowdsourcing, Footprints takes its data integrity seriously by training and supervising its contributors. Once data is entered, the directors have a formal moderation structure in place to ensure quality control (Chesner, Lehman, Shear, & Teplitsky, 2018). When records have errors or do not confirm to standards in some way, they can be flagged manually or automatically for more experienced users to view and moderate. Without clean and accurate data, Footprints is nothing so this point is especially important to its founders and contributors.

- Accessibility

The entire purpose of Footprints is to make otherwise inaccessible data accessible to the public. Therefore, Footprints is an open-source and open-access tool. Its source code is easily available on Github and can freely be copied, distributed, and modified, as long as the changes are tracked in the source files. The data that is available on the site is held under a Creative Commons Attribution + Share Alike 4.0 License. This means that it can be freely copied, distributed, and modified. Attribution to the original author and changes must be tracked in the source code (Footprints, n.d. “Frequently Asked Questions”). Scholars are choosing to add their newly researched information to Footprints, rather than saving it for their own publications, because they see the value in the “trusted crowdsourcing model” of Footprints (ibid.). The new data is able to be put to use immediately and users are able to frame research questions as well as use the database to answer their questions. Footprints allows for an immediate give and take by scholars regarding the research they have done or want done.

While the data from individual records is available, improvements can be made to make it more easily and intuitively findable. Advances can also be made to put the material into its context, with historical backgrounds, timelines, and biographies included on the site. This would truly make the data accessible and easy to understand by those that may not be experts in the field.

- Flexibility

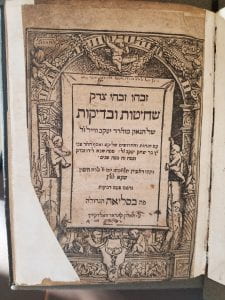

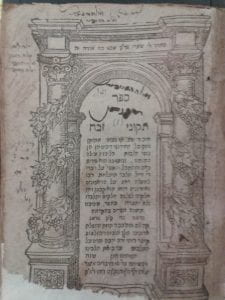

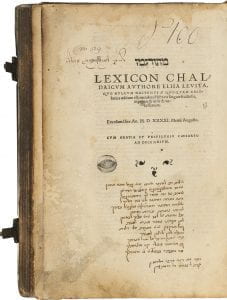

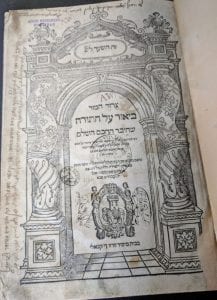

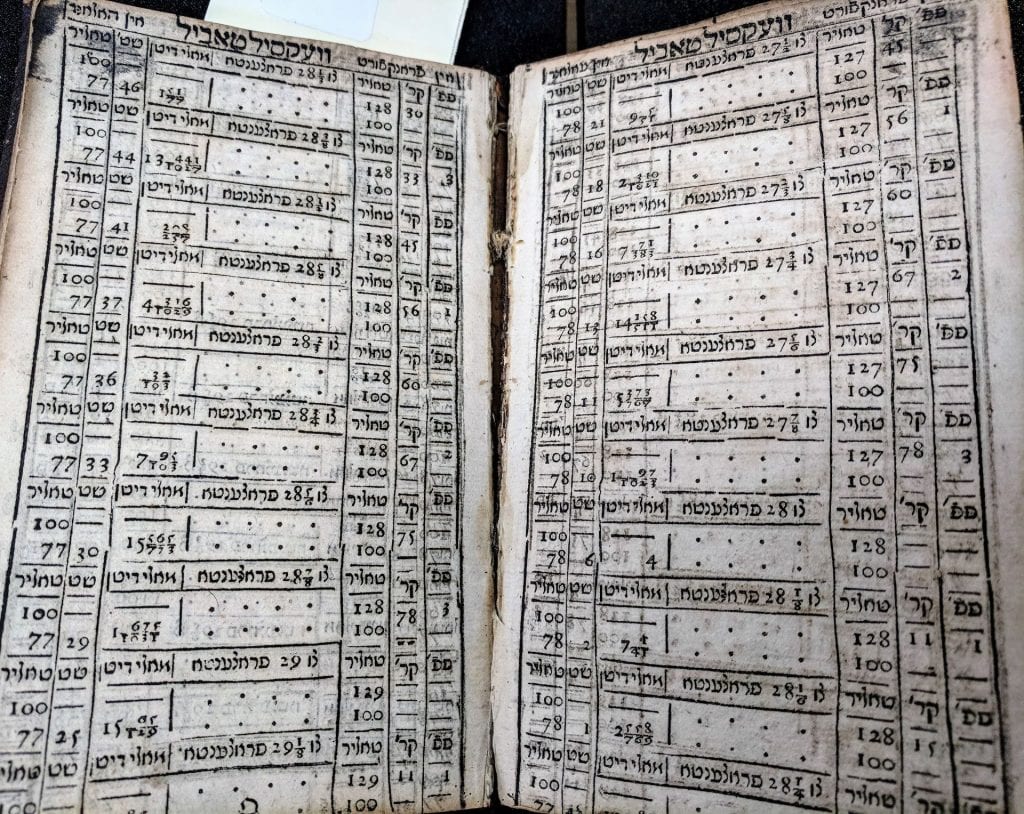

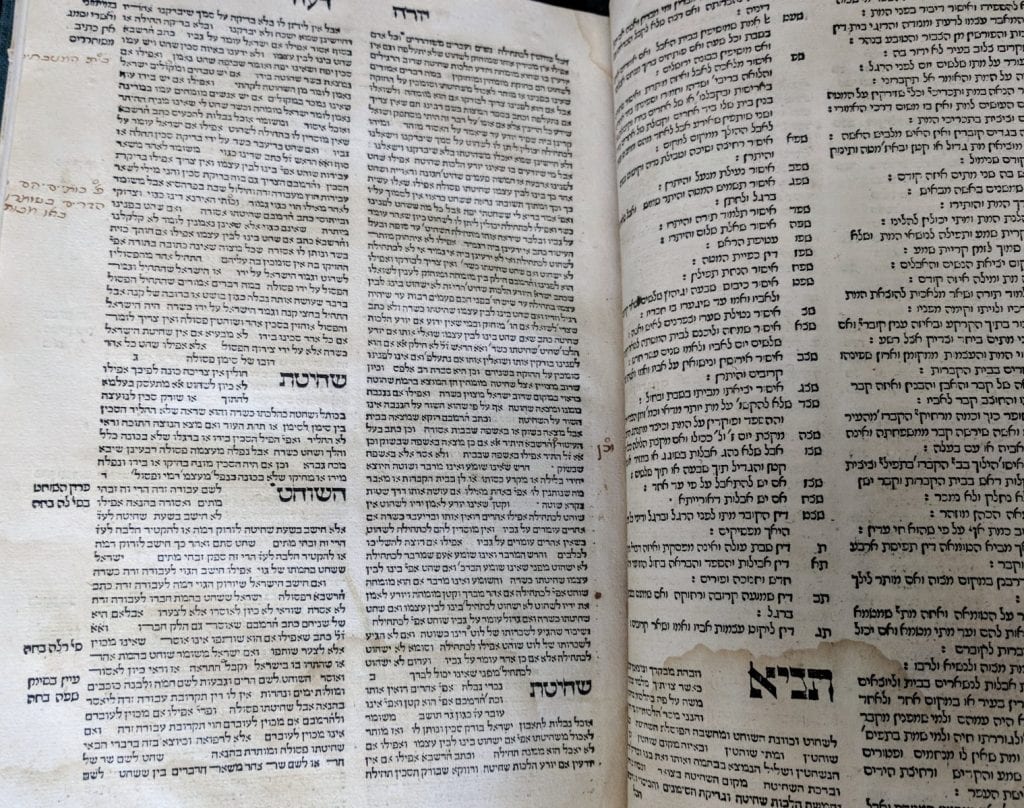

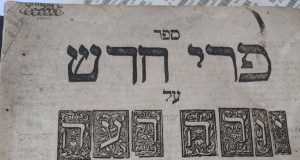

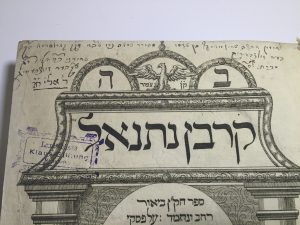

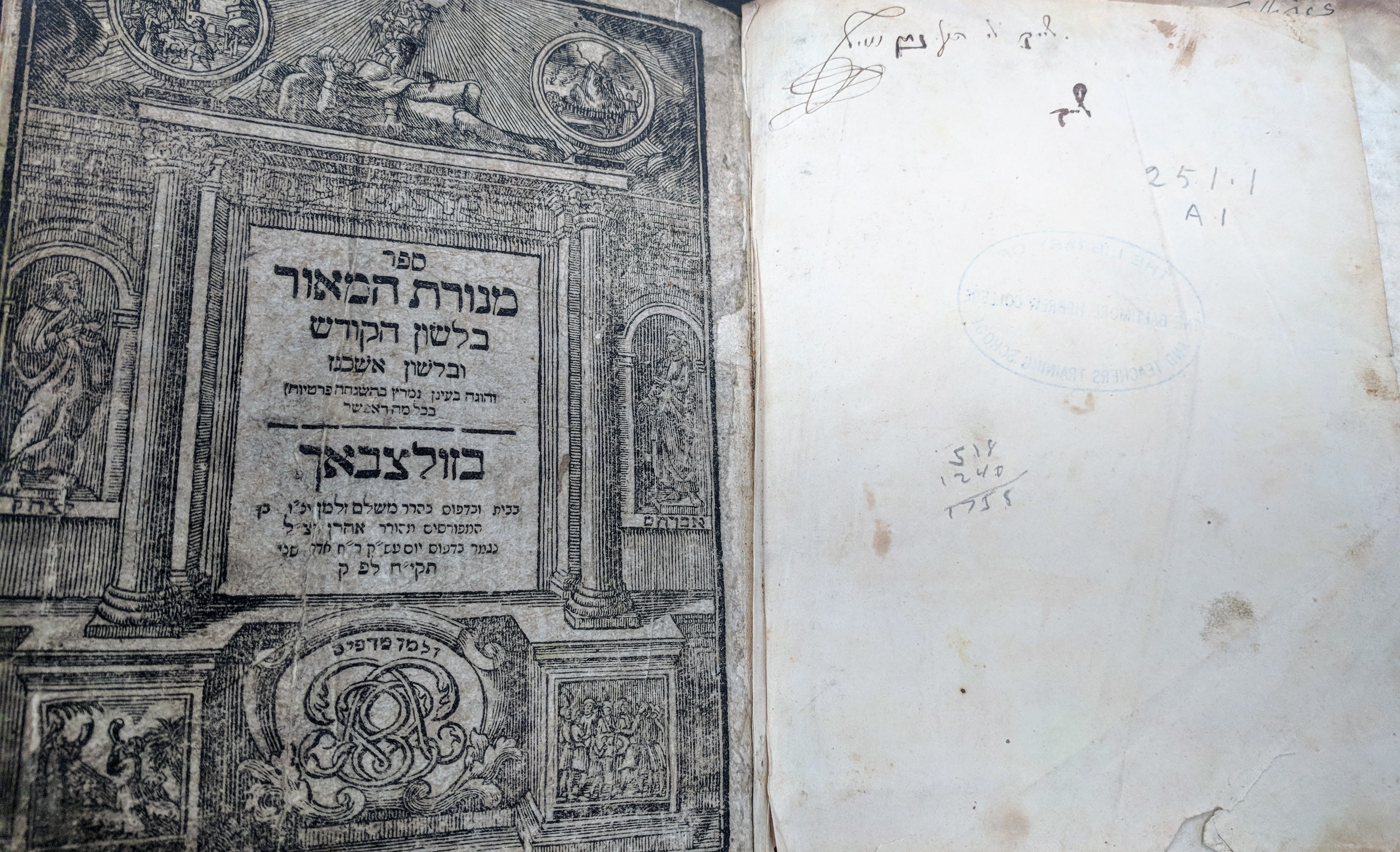

Footprints’ openness to technological experimentation with different platforms and media for ingesting content has contributed to its success since inception almost ten years ago. What grew out of a conversations among experts has become a worldwide project due to the project’s willingness to adjust as situations demanded. It is often assumed that crowdsourcing projects start out well and then stagnate, but if the developers move with the project then they can be successful for longer terms. Footprints has a focus of Jewish books that were published from the late 1400s until the 1850s, but the project is flexible with the definition of Jewish books, as well as those dates when specific situations warrant. The project directors have chosen to focus the year 2018 on incunabula to develop that area of the database, while also adding data related to other texts when pertinent (Shear, 2017). They are committed to ingesting as many footprints as possible and will look for incunabula first, but will not stop there.

Footprints is set up to allow for micro and macro data to be added to allow for as many types of uploads as possible. Larger institutions can add their data by using the batch upload option, while individual scholars may choose to input information piece by piece (Chesner, November 2016). The various methods for adding information show Footprints’ commitment to as many types of contributors as possible. They welcome contributions from these large institutions, smaller archives, private collections, as well as single pieces of data that scholars and librarians come across through their own research. By casting a wide net for contributions, Footprints is allowing the project to grow and develop organically.

Conclusion

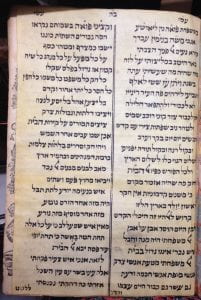

The study of the Jewish book is a perfect example of a field that benefits significantly from a collaborative crowd-sourced model such as Footprints. The scholarship is so dispersed that a united approach to gathering that information will result in increased knowledge regarding the Jews who owned these books and the world in which they lived. Footprints has managed to continuously build an effective model for collaborative crowdsourcing by combining the best ideas for a successful model and plans for future improvements. The co-directors have developed the project by building a community around it, by ensuring that their data and its sources are transparent, that users have access to the information that is being collected, and that there is room for growth and flexibility in their future plans. As Footprints continues to develop and expand its coverage, it will be fascinating to watch the new insights that are learned about the historical time period it covers and their implications for today.

Recent Comments