Shevi Epstein, an MLS student at Rutgers’ focusing on Archival Studies, has been working on entering Footprints at the Katz Center for Advanced Judaic Studies at the University of Pennsylvania. She describes her experience – and discoveries – below:

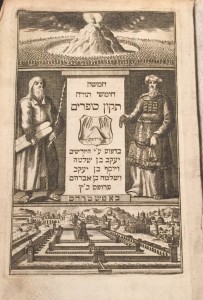

Through my contributions to the database for Footprints: Jewish Books Through Time and Place, I have discovered a wealth of Jewish history, which might have otherwise been lost. Hidden in the various clues left behind by  past generations are details of the movement of these Jewish books over the past 500 years and a glimpse into the lives of those who possessed them.

past generations are details of the movement of these Jewish books over the past 500 years and a glimpse into the lives of those who possessed them.

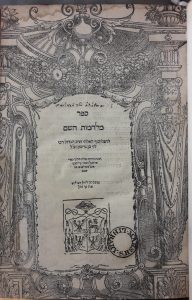

Throughout Jewish history, there have been innumerable attempts to not only wipe out the Jewish people, but also their literature. From the Spanish Inquisition to the Austrian Holy League to the Nazis, the burning of Jewish books has been an efficient way to destroy these materials while simultaneously sending a clear message of warning to the Jewish community. In some sense it is surprising that any Judaic books have survived these waves of destruction. Today, handling the 500 year old books in the collection of the Katz Center for Advanced Studies in Philadelphia is all the more incredible given their survival over the centuries and the journeys that I have had the privilege of piecing together.

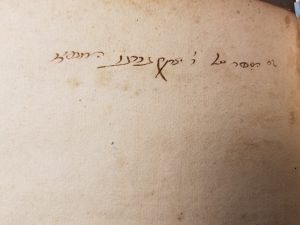

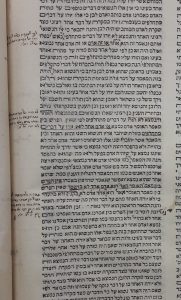

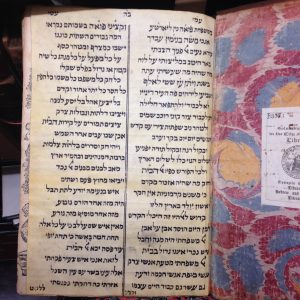

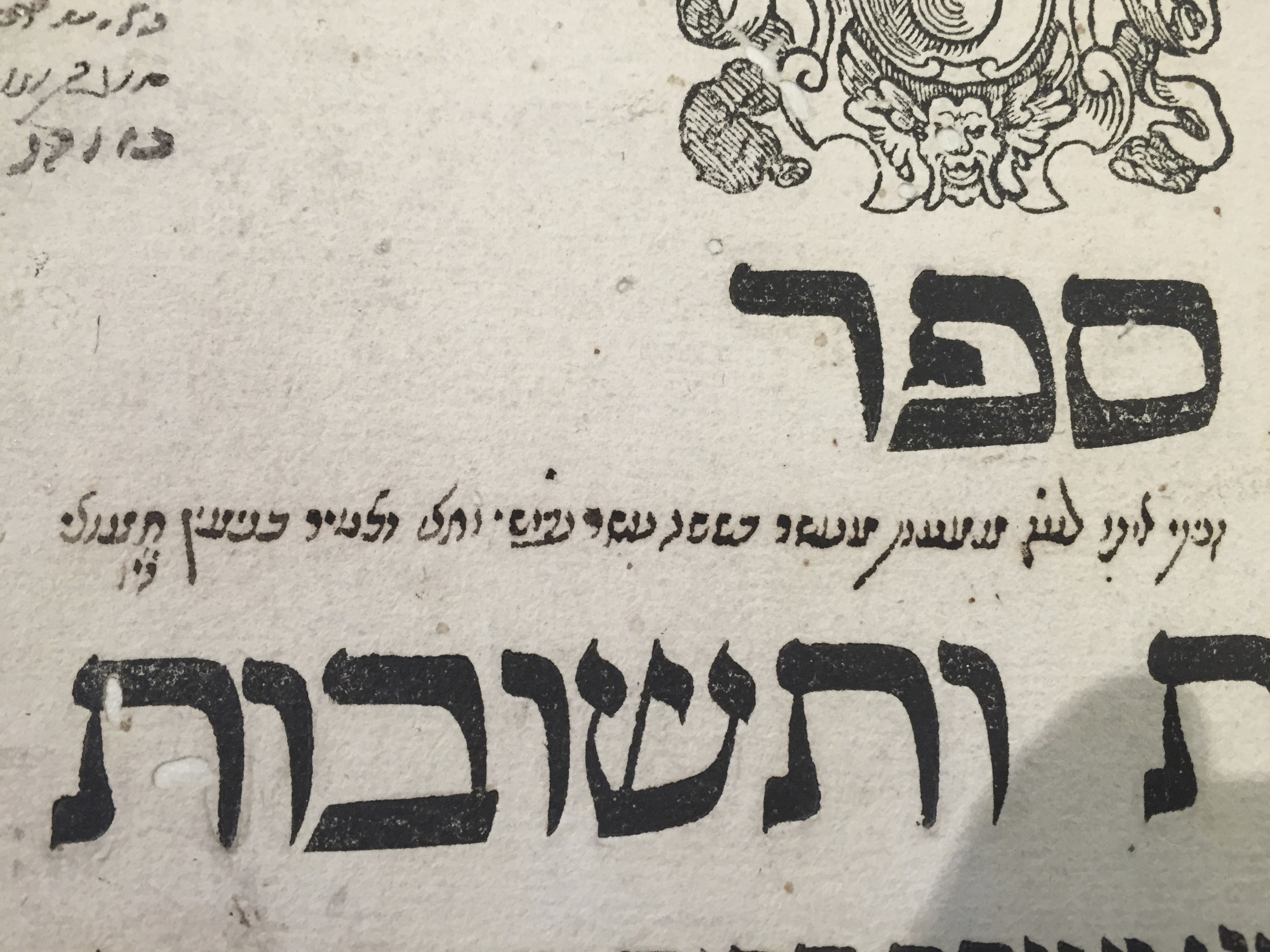

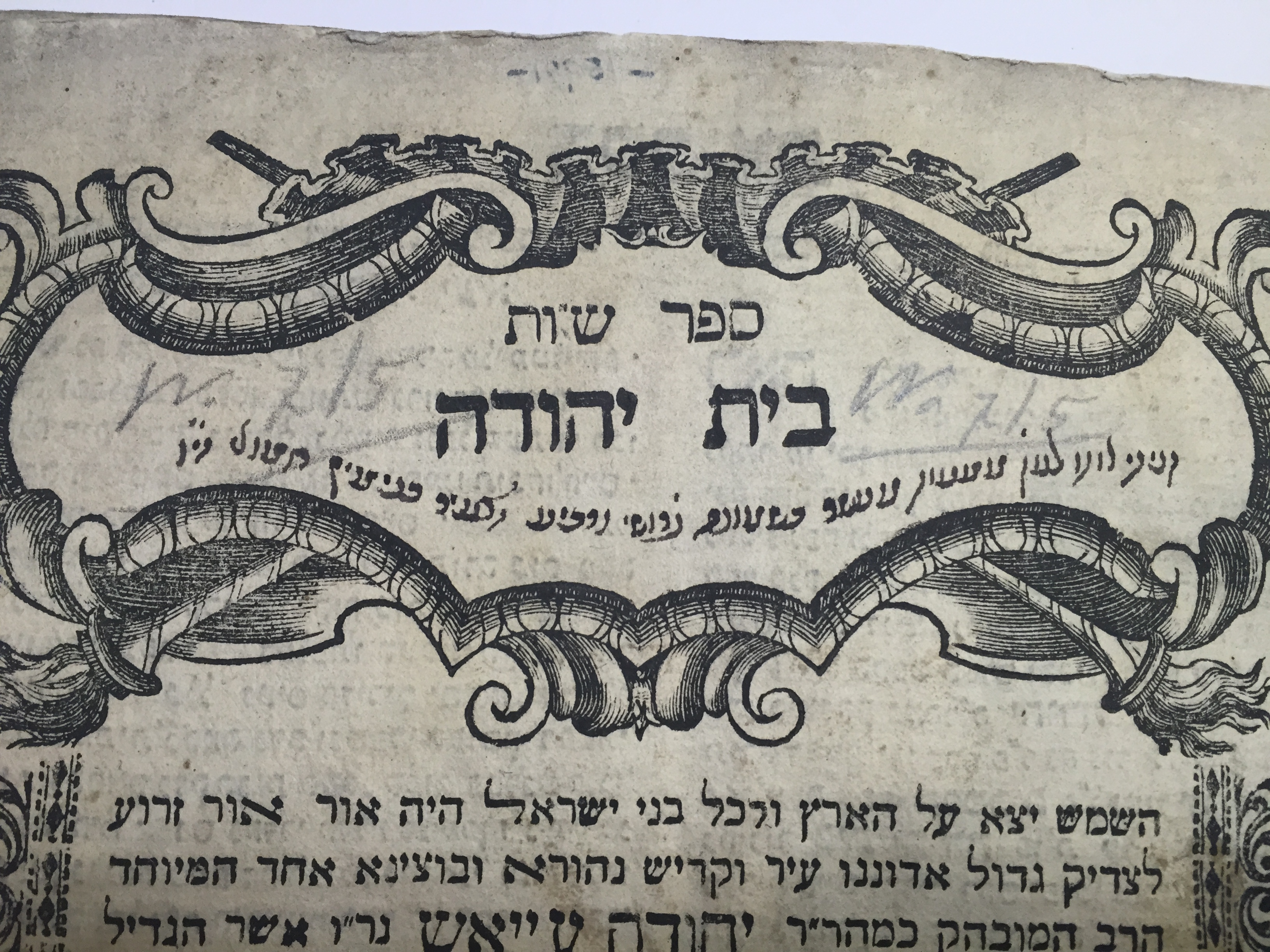

Each book that I examine for this project has had a story to tell. From the carefully written owner signatures, to the meticulous personal notes in the margins, to the playful doodles scribbled across the pages, each mark tells the tale of a well-loved and oft-used book. However, some of the marks left in these books tell of a far more tragic past and of narrow escapes from destruction.

Each book that I examine for this project has had a story to tell. From the carefully written owner signatures, to the meticulous personal notes in the margins, to the playful doodles scribbled across the pages, each mark tells the tale of a well-loved and oft-used book. However, some of the marks left in these books tell of a far more tragic past and of narrow escapes from destruction.

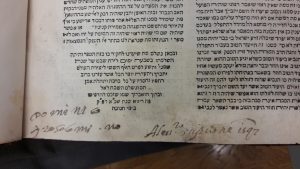

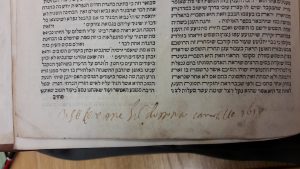

Some of the most important clues I look for when investigating the history of a book are the signatures of expurgators. These censors were typically Jewish who had converted to Catholicism working for the Catholic Church who would analyze Jewish books in search of any passages that were  antithetical to the teachings of the Church and cross them out. They would sign their name at the end of the book and, usually, include the date to demonstrate that the book had been reviewed and censored. Some books contain as many as eight censor signatures, ranging from the 16th through the 17th centuries. Despite the clearly unethical practice of cultural erasure, the scratched-out lines and signatures that were left in these texts likely saved not only the books themselves from destruction, but their owners from further persecution related to the possession of the texts.

antithetical to the teachings of the Church and cross them out. They would sign their name at the end of the book and, usually, include the date to demonstrate that the book had been reviewed and censored. Some books contain as many as eight censor signatures, ranging from the 16th through the 17th centuries. Despite the clearly unethical practice of cultural erasure, the scratched-out lines and signatures that were left in these texts likely saved not only the books themselves from destruction, but their owners from further persecution related to the possession of the texts.

Many of the owners of these books were not lucky enough to survive the destruction that the markings in these books describe. Some of the books I come across contain stamps from the Reich Institute for the History of New Germany, which aimed to study the “Jewish Question” and justify the Nazi regime’s anti-Semitic platform through science.

Many of the owners of these books were not lucky enough to survive the destruction that the markings in these books describe. Some of the books I come across contain stamps from the Reich Institute for the History of New Germany, which aimed to study the “Jewish Question” and justify the Nazi regime’s anti-Semitic platform through science.

These books almost always additionally contain a bookplate from the Jewish Cultural Reconstruction, Inc. The Jewish Cultural Reconstruction, Inc. was an organization in the American occupied zone of southern Germany from 1947-1952, tasked to collect and redistribute stolen Jewish property. Books in the collection of the Katz Center for Advanced Studies that contain this bookplate were from the group of books redistributed to Dropsie College in Philadelphia as their original owners had been killed in the war or could not be found.

Bought, sold, donated, stolen, redistributed, censored, gifted, and passed down through the generations, the history of Jewish books and the Jews who owned them are being carefully retraced by the participants in the Footprints project. Their efforts are shedding light on the long and hard road that has brought these books to where they currently reside and on all those who, for better or worse, had a hand in that process.

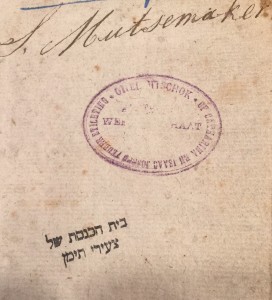

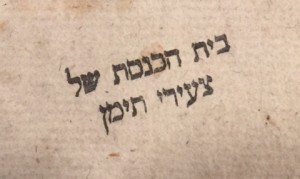

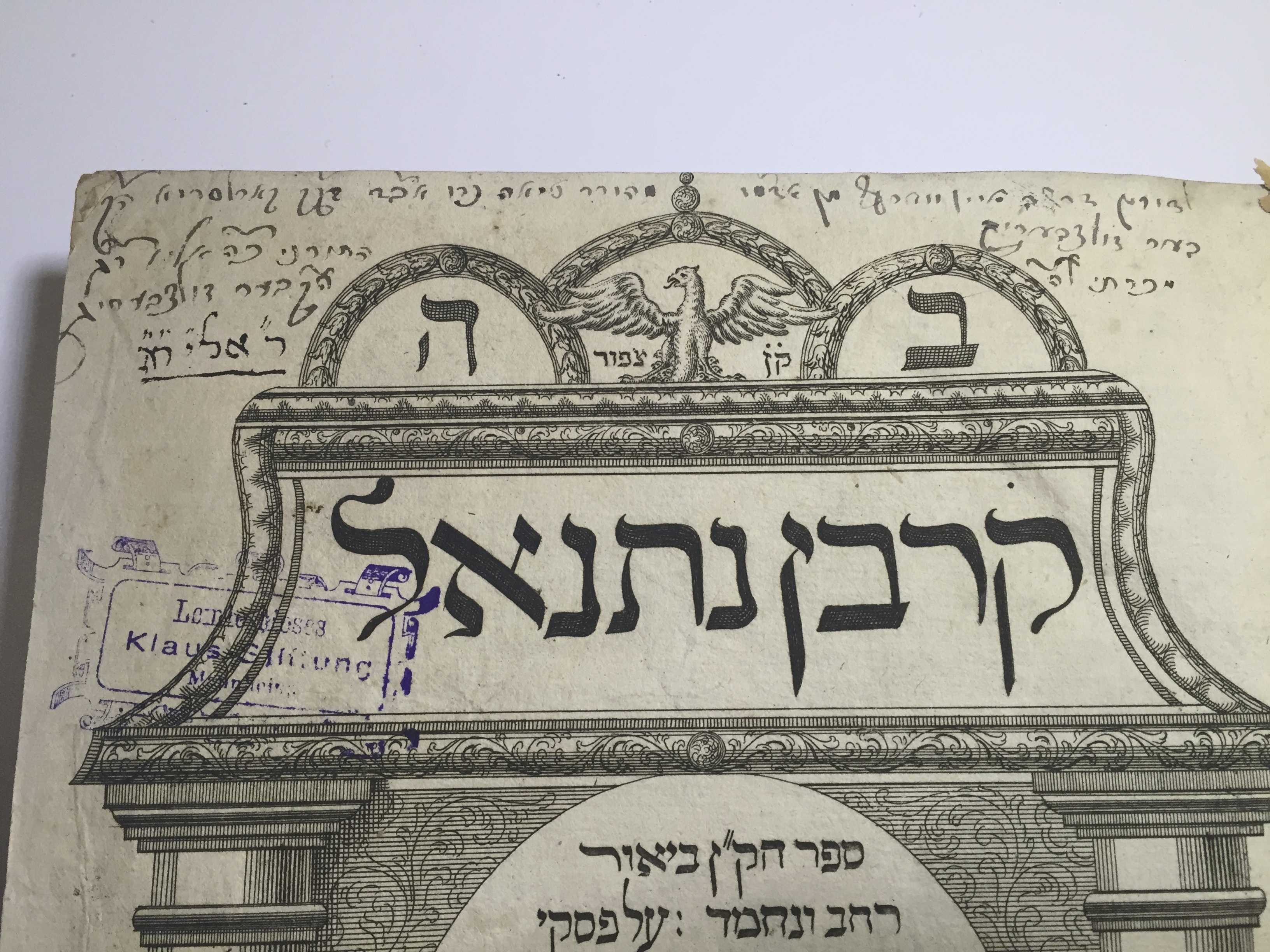

The third footprint was a stamp in purple ink indicating that the book had been owned by

The third footprint was a stamp in purple ink indicating that the book had been owned by

Recent Comments