“Ranaldo Sconfitto: an Alternative Ending to the ‘Rocca Crudele’ Episode of the Orlando Innamorato.” Original images and exhibition labels by Christina Lopez (PhD, Columbia University); in the context of the course “Renaissance Chivalric Epic and Folk Performance Traditions,” Prof. Jo Ann Cavallo, Department of Italian, Columbia University. May 2016.

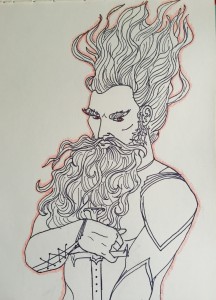

- Marchino

Marchino, il sir de Aronda, se chiamava.

Lui fu menato dentro a questa stanza,

Ed onorato assai, come era usanza.

Or, come volse la disaventura,

Gli occhi alla bella Stella ebbe voltato,

E fo preso de amore oltra misura,

E seco pensò il viso delicato

Di quella mansueta creatura;

In summa, è dentro il cor tanto infiammato,

Ch’altro nol stringe, né d’altro ha pensiero,

Se non di tuor la donna al cavalliero (1.8.30-31).

Marchino is depicted with an imposing corporeality, and the largeness of his form foreshadows the terrifying bulk of his monstrous offspring. The use of red symbolizes not only eros here, but also bloodshed, as his mad lust for Stella drives him to commit repeated acts of horrifying brutality. The unsheathed dagger in his hand explicitly references the murders he commits in the “Rocca Crudele” episode, as well as his eventual violent death at the hands of the subjects of King Orgagna.

- Grifone and Stella

Un cavallier di possanza infinita

Di questa rocca un tempo fu segnore.

Vita tenea magnifica e fiorita,

Ad ogni forastier faceva onore;

Ciascun che passa per la strada invita,

Cavallier, dame e gente di valore.

Avea costui per moglie una donzella,

Che altra al mondo mai fu tanto bella.

Quel cavalliero avea nome Grifone;

Questa rocca Altaripa era chiamata,

E la sua dama Stella, per ragione,

Ché ben parea del celo esser levata (1.8.28-29).

Grifone and his beautiful wife, Stella, are here styled so as to evoke portal sculptures typical of Romanesque churches; their long figures are placed on pedestals and ensconced beneath an arched frame whose style is typical of late medieval churches. Their gestures of prayer and soft gazes signal their innocence and ignorance of the horrific events to come, and the blue aura that surrounds them further symbolizes the tragic nature of their story.

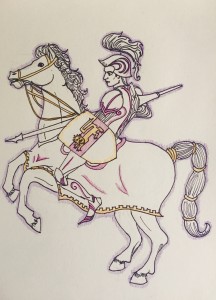

- Ranaldo

Mosse pietate quel baron gagliardo:

Benché sia a piedi, armato con la spada

A seguire il ladron già non fu tardo;

Coperto d’arme corre quella strada (1.8.18).

Ranaldo, the hero of this episode, is approached by an old man who begs the knight to rescue his kidnapped daughter; moved by pity, he immediately sets out, pursuing the villain on foot. In the course of this pursuit, Ranaldo is captured and imprisoned in the Castel Cruel, where he learns of the terrible tragedies that took place there. The aging wife of Marchino narrates the disgusting instances of his rape of Stella (first when she was alive, then after he murdered her by slitting her throat), his various betrayals (of Grifone’s courtesy and of his marriage vows to his wife), and the many gruesome murders that took place as a result of Marchino’s insatiable (blood)lust (his assassination of Grifone and Stella, the murder of her sons and her feeding them to her husband, and the townspeople’s violent laceration of Marchino). This cycle of violence ultimately inspires Ranaldo to battle the beast in an attempt to set the town free from the spirit of cruelty that dominates there. Here shown in gold and purple (colors evocative of royalty), Ranaldo’s youth and prowess are underlined by his elaborate armor, strong figure, and powerful horse. His shield is embossed with the image of a lion, yet another symbol of his courage and commitment to the chivalric code.

- The Monster

Egli era più che un bove di grandezza:

Il muso aveva proprio di serpente;

Sei palme avea la bocca di longhezza,

Ben mezo palmo è lungo ciascun dente.

La fronte ha de cingiale, in tal fierezza

Che non si può guardarla per nïente;

E di ciascuna tempia usciva un corno,

Che move a suo piacere e volge intorno.

Ciascuno corno taglia come spata;

Mugia con voce piena di terrore,

La pelle ha verde e gialla e varïata

Di negro e bianco e di rosso colore;

Avea la barba sempre insanguinata,

Occhi di foco e guardo traditore;

La mano ha d’omo ed armata de ungione

Maggior che quel de l’orso o del leone.

Ne l’ungie e dente avea cotanta possa,

Che piastra o maglia non li può durare;

E la pelle sì dura e tanto grossa,

Che nulla cosa la potria tagliare (1.8.57-59).

Boiardo describes the monster in great detail, rendering a monstrous figure who possesses a multiplicity of forms: the girth of an ox, the snout and fangs of a serpent, the chest of a wild boar, horns like a ram, hard, reptilian skin blotched various colors, a bloody beard, and the hands of a man with long nails. The references to treachery call to mind a less terrifying creature: Geryon of Inferno XVII (La faccia sua era faccia d’uom giusto/ tanto benigna avea di fuor la pelle/ e d’un serpente tutto l’altro fusto) (v. 10-12). The product of Marchino’s rape of Stella’s corpse, this monstrous creature embodies the bloodlust of his father and is a visual incarnation of the violence and depravity that led to his conception.

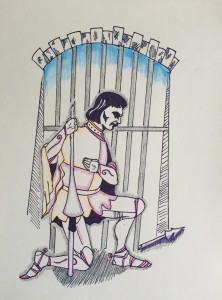

- Ranaldo Defeated

Or se ’l destina in tutto di stordire:

Mena un gran colpo quel baron soprano.

La mala bestia il brando ebbe a gremire:

Or che dee far il sir di Montealbano?

Diffender non si può, né può fuggire,

Perché Fusberta li è tolta di mano.

Ma poi vi dirò come andò il fatto:

In questo canto più di lui non tratto (1.8.64).

Boiardo concludes the eighth canto with the impending battle between the heroic Ranaldo and the ghastly beast. In the original version of the “Rocca Crudele” episode, Ranaldo is saved by Angelica, motivated by her powerful (and unrequited) attraction to the knight. After he defeats the monster, however, he is attacked by the townspeople who plan to execute him. In my reimagining of the tale, I propose a different turn of events, whereby Ranaldo is unable to vanquish the beast. Still in his trademark colors of gold and purple, Ranaldo’s nobility is unfading, yet the broken lance, kneeling position, and bowed head all signify defeat. The shadows on his face render him weary and wretched, and he is imprisoned in the Castle Cruel, which is evoked by the blue shadows outside his prison cell (the melancholy hues of the original proprietors of the castle, Stella and Grifone).

- Orlando’s Victory

E vedereti i gesti smisurati,

L’alta fatica e le mirabil prove

Che fece il franco Orlando per amore

Nel tempo del re Carlo imperatore.

Non vi par già, signor, meraviglioso

Odir cantar de Orlando inamorato,

Ché qualunche nel mondo è più orgoglioso (1.1.1-2).

In my recreation of the “Rocca Crudele” episode, I conclude the tale with a valiant Orlando coming to save Ranaldo from the bloodthirsty townspeople. He is indeed the hero of the Orlando innamorato and the Orlando furioso, and so I make him the true hero of this episode. Motivated by chivalric duty and a desire to demonstrate his prowess to Angelica, he saves the vanquished Ranaldo. By rescuing him, Orlando attempts to humiliate his heroic cousin in an effort to win Angelica’s love. Orlando stands proudly before the Castle Cruel (outlined in the signature blue hue of Stella and Grifone); he is surrounded by an indigo aura, indicating the grief and eventual madness he suffers for his love of Angelica. Finally, his flag is white, outlined with red, white signifying peace and crimson symbolizing the martial enterprises of the famed Orlando.

Reflections on My Creative Process and Decisions:

The “Rocca Crudele” episode stands out among the many adventures within the Orlando innamorato as being particularly horrific, and my meditation on alternative endings began with the perturbation I felt upon reading it. Shocked by the extreme sexual violence and perverse bloodshed, I wondered how the performers of the Maggio tradition and the Sicilian puppeteers could possibly render this graphic textual moment; I realized shortly thereafter that it is in fact essentially absent from these theatrical entities. The tendency of these performative traditions to excise or transform content that their performers deem too controversial or inappropriate for audiences that typically contain children further inspired me to reflect on how this episode could be transformed.

While I perfectly enjoyed the ultimate resolution of the tale (I must say that I very much liked the fact that it is a woman who saves Ranaldo from the bloodthirsty townspeople), I still felt unsettled by it. Thanks to Angelica, Ranaldo defeats the monster, and, when the townspeople attempt to kill him, he kills them instead and sends the rest fleeing; this, of course, has a very particular set of textual implications. Angelica swoops in on a flying beast and saves her beloved, but not without first making a lusty offer for him to ride her in the way that she is riding her beast. The moment serves to illustrate Angelica’s lust, which the good Christian knight finds repulsive, and it gives Ranaldo yet another chance to reiterate his lack of attraction to Angelica. These textual elements naturally serve the purpose of restating the complicated relationship between Ranaldo and Angelica, yet I was even more fascinated by the longstanding competition throughout the Orlando innamorato between Orlando and Ranaldo. Their relationship is truly complicated, as they compete against one another first over issues of knightly valor, and later for love of Angelica. Their duels transcend the physical, and veer frequently into violent verbal spars in which each vigorously derides the other, leaving the reader to determine who is the worthier knight. As Michael Sherberg points out in his article, “Matteo Maria Boiardo and the Cantari di Rinaldo”: “In the duel at Albraca, the blows are even; with perfect symmetry Ranaldo answers each of Orlando’s strikes against him. Final judgment falls to the reader, who will side with Orlando or Ranaldo on the basis of his knowledge of the chivalric code, his familiarity with and preferences within the tradition, and his knowledge of the specific cases cited by the knights” (172). Given the ambiguity surrounding the competition between them (which can be detected in Boiardo’s attempts to expose the flaws of both knights), it seemed to me that the more interesting issue in the text is the relationship between the heroic cousins.

With this in mind, I wanted to create an ending to the “Rocca Crudele” episode that further problematizes the already litigious relationship between Orlando and Ranaldo. By having Orlando triumph over both the monster and the townspeople, it elevates him over his cousin and casts a more favorable light on the titular hero of Boiardo’s epic work. Orlando, in the ending I create, is not only the victor of the struggle against the monster and the denizens of the town, but he is also the victor over his cousin – he bests him in this competition for chivalric prowess. Furthermore, by liberating his cousin and freeing the town of the terrible creature that has plunged it into a perennial cycle of violence, he performs another impressive act in the hopes of winning Angelica’s approval. In this sense, my reinterpretation of the Castle Cruel affair serves to problematize both the familial relationship between Orlando and Ranaldo and the amorous relationship between Orlando and Angelica, connections that Boiardo already presents with great complexity in his text.

Christina McGrath (Columbia University)

Works Cited

Boiardo, Matteo Maria. Orlando Innamorato. Ed. Andrea Canova. Milano: BUR, 2011. Print.

Sherberg, Michael. “Matteo Maria Boiardo and the Cantari Di Rinaldo.” Quaderni d’Italianistica: Official Journal of the Canadian Society for Italian Studies 7.2 (1986): 166. Web.