Archaeobotanical and scientia plantarum studies and the natural imagery in Boiardo’s Inamoramento de Orlando.

By Cecilia Marchetti (PhD student in Humanities, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia)

Research objectives and expected research outcomes

The garden has always evoked images and suggestions in the human mind that recall the idea of Paradise, as it represents a feeble attempt by human beings to emulate divinity. Through effort and dedication, humans manage to tame Nature, bending it to their desires and becoming creators of a fictional and ephemeral Eden, subject to earthly laws that determine its periodic withering and eventual death. The hortus conclusus, a delimited and circumscribed space, is therefore a completely independent and self-sufficient system, separate from the external environment, where plants and flowers grow in harmony with each other, thus creating a perfect ecosystem.

The House of Este has a deep connection with the natural world, particularly with gardens. This relationship is demonstrated both by the numerous handwritten and printed testimonies preserved within the Estense Library and the State Archive of Modena, and by the significant effort promoted by the Estense family in creating many green areas, especially in the city of Ferrara.

The hanging gardens, the golden fountains, and the numerous species of flowers and plants that were part of the fragile urban ecosystem have now disappeared due to the relentless passage of time and the decline of the duchy. However, the natural images evoked by the real loci amoeni still reverberate in the pages of Boiardo’s Inamoramento de Orlando, generating fantastic landscapes where the adventures of the paladins unfold. These places possess an immeasurable beauty that fascinates knights and hosts enchantresses, becoming synonymous with attraction and perdition, just like the garden of the fairy Falerina in Boiardo, from the Este perspective, the garden becomes a symbol of power, scientific research, the worship of hedonism, and conviviality.

The project capitalizes on the scientia plantarum of the era and insights from archaeobotany, enabling a revival of the lost gardens of the Este duchy, including the Garden of the Duchesses and Eleonora d’Aragona’s Hanging Gardens. It seeks to unveil the intricate relationship between Renaissance flora and natural elements depicted in Boiardo’s works. A comprehensive multidisciplinary approach encompassing archaeobotanical studies, analysis of Este iconography, exploration of contemporary plant science (notably the “Este Herbarium”), examination of natural elements in Orlando Innamorato, and AI technology has been instrumental in recreating these iconic gardens.

Archaeobotany

The first approach of the project was to investigate and analyze the Este gardens from a botanical point of view. To fully understand the urban project of Ercole I d’Este, I am collaborating with Dr. Giovanna Bosi, a researcher at the Faculty of Life Sciences of the University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, whose contribution is valuable in deepening the aspects related to archaeobotany and research on historical green spaces. The gardens we will deal with have all disappeared or drastically changed from their original appearance. The history of green spaces before the modern age is an “archaeological” narration, based on documents and fragmentary remains found during the excavations. It is a story of traces, in which the true protagonists, the plants, no longer exist. The gardens must therefore be reconstructed. Between 2000 and 2013, archaeological excavations were carried out in the context of the redevelopment works of the historic center of Ferrara. The excavations helped to reveal new details about the history and court life of Ferrara at the time of Ercole I d’Este, highlighting the importance of the royal gardens as spaces of historical and artistic relevance: ducal courtyard / municipal square, garden of the duke or duchess, hanging garden of Eleonora d’Aragona.

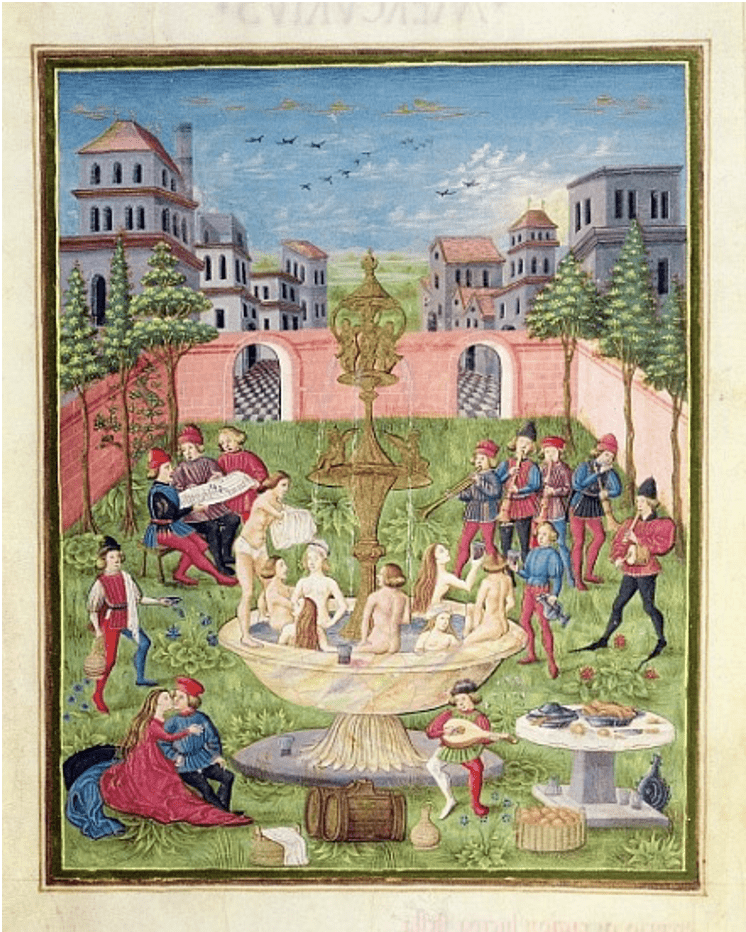

One of the most fascinating discoveries of the excavations is a vanished garden of great importance, known as the “Duke’s Garden”, commonly referred to as the “Duchesses’ Garden”. Built between 1473 and 1481, its creation involved the removal of previous buildings such as stables, warehouses and cellars, as confirmed by historical sources. Within this garden stood a sumptuous golden fountain, which, unfortunately, has not survived as it was destroyed in 1531. The only remains that bear witness to its ancient existence are the traces of pipes and foundations, which however do not provide us with detailed information about its shape. The sources suggest that the fountain was decorated with precious marbles and refined sculptures. The certainty of its gilding is confirmed by documents that record the payment to Giovanni Trulo “for having gilded the fountain of the garden of our Lord”.

The carpological and pollen analysis revealed the plants that adorned the duchess’s garden, such as laurel, fennel, juniper, carnation, myrtle, holm oak, poppy, pine and rose.

Figure 1 Reconstructive hypothesis of the appearance of the Duchesses’ Garden (drawn by Riccardo Merlo) Guarnieri, 2018, p.337.

The botanists reconstructed the likely layout of the “Garden of the Duchesses” by referring to iconographic sources from the era of the duchy of Ercole I d’Este. Among these, the most notable are the miniatures in the De Sphaera manuscript and the frescoes at Palazzo Schifanoia. They speculated that the golden fountain ordered by Ercole d’Este was inspired by the miniature of “The fountain of youth” in the De Sphaera manuscript, which dates back to around 1470 and is now kept in the Estense Library.

Through a thorough phyto-iconographic analysis conducted on the famous frescoes of the Salone dei Mesi painted by Francesco del Cossa at Palazzo Schifanoia in Ferrara, a remarkable convergence emerged between the plant species portrayed in the wall paintings and those documented in the contemporary environment, both from a pollen and carpological point of view. The myrtle, the white and red roses, and the carnations are among the most prominent species, appearing in the hands of the young courtiers crowned with roses by Venus in the “Triumph of Love” and in the love garden of the “Month of April”. This synergy between documentary sources and artistic works sheds new light on the possible influence of nature in the creation of symbolic and suggestive environments, highlighting the crucial role of plants in this process.

Figure 3 The triumph of Venus, detail of the Month of April in the Hall of Months in Palazzo Schifanoia in Ferrara

The Este Herbarium

An important source for understanding the botanical knowledge of the time is the Estense Herbarium. The Este Herbarium is a priceless manuscript, kept at the State Archive of Modena. Its author is unknown, but it was likely made by a court gardener. It has no date, but it was probably created in the late 16th century. It contains 182 plant samples, dried and preserved: the horti sicci. The Este Herbarium is part of Lodovico, an open and cross-disciplinary platform developed by the Interdepartmental Research Center on Digital Humanities of the University of Modena and Reggio-Emilia (DHMoRe).

Figure 4 example of metadata sheet with current and nineteenth-century scientific nomenclature of the relative botanical changes.

The herbarium of Inamoramento de Orlando

A key component of the project is the philological analysis, which involved identifying the instances of plant references, particularly plants and flowers, within Orlando Innamorato. The work of Matteo Maria Boiardo, Inamoramento de Orlando, is full of references to gardens and natural settings that provide the scenery for the characters’ adventures. The plant instances in the work were manually detected, resulting in 25 different taxa: Fir, Laurel, Orange, Cedar, Cypress, Beech, Ash, Fennel, Carnation, Mulberry, Hyacinth, Juniper, Larch, Holm oak, Myrtle, Olive, Elm, Palm, Poppy, Pine, Poplar, Oak, Rose, Cork, Violet.

These are plants that belong to various botanical families. Many of the natural varieties found in Boiardo’s work can also be seen in the Este gardens, along with some ornamental features of the gardens, such as loggias, pergolas and fountains. This demonstrates the tight connection between literature and art of the Italian Renaissance, which mutually influenced each other to produce works of beauty and harmony.

Figure 5 Example of a record of natural occurrences in Inamoramento de Orlando, indicating the plant type, the location and the situation in which it was employed.

Artificial gardens

Based on the outcomes of the research performed by the archaeobotanists, I am proposing a novel approach that utilizes artificial intelligence to interpret the data and the archaeological evidence at hand. DALL·E is a cutting-edge artificial intelligence model, created by OpenAI. It possesses the remarkable ability to generate coherent and relevant visual images from textual descriptions.

I aim to explain how my approach differs from previous methods and how it can contribute to the advancement of archaeobotany. I will also demonstrate how DALL·E can be used to create realistic and informative images that illustrate the ancient plant life and human-plant interactions in different regions and periods. By combining artificial intelligence and archaeobotany, I hope to shed new light on the past and present of our relationship with nature.

Figure 6 Image created with Dall-e based on the archaeobotanical reconstruction of the Duchesses’ Garden.

Furthermore, the descriptions of the gardens evoked by the Este poets will take shape with the help of artificial intelligence technology, like Dall-E. The verses of Boiardo and Ariosto, through a synesthetic process, will transform into images to evoke the natural suggestions present in their works. The words of the poets will thus become visible, what Dante in the Commedia defined as “visibil parlare”, a new form of communication that is unknown to human art and nature.

This new synesthetic approach will highlight the relationship and the contamination between reality and fiction. As in a game of mirrors, the Este reality is reflected in the words of the court authors.

Their words are like mirrors that reflect the reality of their time, but also distort it and transform it into something new and fascinating. The intent of the poets is to filter the Este reality through magic and fantasy, to bring wonder and enchantment to their pages. They create a world where the natural and the supernatural coexist, where the gardens are populated by mythical creatures and marvelous adventures.