Why screen?

Immunization and Chemoprophylaxis

Screening

Education and Counseling

Many people who come to the doctor for a “check up” often expect that the visit will pick up asymptomatic diseases. The definition of screening is the strategy used in a population to identify individuals with an unrecognized disease or risk factor. Screening entails not only performing laboratory tests (e.g., fasting blood glucose level) or a procedure (e.g., colonoscopy), but the actual patient’s history (e.g., age, tobacco use, sexual behavior) and physical examination (e.g., blood pressure measurement, breast exam). Most screening is not diagnostic. If the screen is abnormal, it will lead to further examinations, testing, or procedures (e.g., repeat blood pressure check, repeat glucose testing, and breast biopsy); thus the patient and physician should be prepared for further evaluation if necessary.

How is a good screening test determined?

There are a myriad of examinations, tests, and procedures that can be offered to an individual, but determining who should receive what screening services, when, and how often can sometimes be unclear or controversial.

The World Health Organization (WHO) delineated the principles of screening that should be met before an intervention is initiated.

| World Health Organization – Principles of Screening (WHO, 1968) |

|---|

|

The Harms and Challenges of Screening

The fundamental prevention principle of detecting preclinical disease may have downsides that cannot be ignored. Screening may have a harmful effect even if an abnormal result is found early. Procedures and tests may be unsafe. Tests with high false negatives may clearly miss the opportunity to reduce morbidity and mortality of targeted disease and may have legal ramifications. There is always concern for the possible lack of follow up by patients or clinicians for the results of a true positive test. A procedure may be too expensive or inaccessible to the people who would benefit most; it may be too painful for a patient to tolerate, or too complex for a patient to adhere.

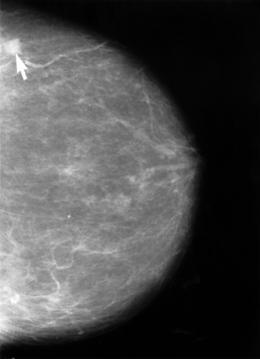

Any abnormal result whether a false positive or true positive may cause distress, anxiety, and depression—also known as the “labeling effect.” In our enthusiasm to spare our patients from chronic illnesses, we present the label of hyperlipidemia, prediabetes, osteopenia, or elevated PSA, possibly creating a new population of patients who prematurely identify themselves as ill. As one prominent health care policy academician has written in the New York Times, “Is looking hard for things to be wrong a good way to promote health (G. Welsh 2012)?” From some unlucky patients’ perspectives, screening for disease may promote illness and labeling rather than health. For example, distorted breast architecture may result from a complicated biopsy of a benign breast mass discovered on a routine mammogram; and atypical fractures may result from bisphosphonates used to treat low bone density in women without a history of fracture. These examples are reminders that practitioners should have an extremely high bar of evidence for introducing a preventive measure into a healthy population. Controversies in preventive medicine, such as mammography in women 40 to 49 years old or prostate cancer screening, require a skillful clinician to guide a shared decision about the best clinical pathway to take.

Some points to consider about when not to screen:

- The service benefits no or very few people in the target population

- The service has no or little effect in the target population

- The condition has low prevalence in the target population

- The screening is “unfocused” (ordering a “Chem 12” rather than just a “Basic Metabolic Panel” may pick up more abnormalities that may not be clinically significant).

- The service causes net harm in the target population.

- There is uncertain balance of benefits and harms.

Returning to our case:

Y.S. is 24 year old white female medical student who presents to you in student health clinic today for her first visit. She has no complaints but just wanted “a checkup”. She is generally healthy and had only a past medical history of acne that has resolved. She takes no medications currently and has no known drug allergies. She has no history of surgeries. Y.S. denies any mental health history. She has been sexually active only with her boyfriend for three years. They use condoms exclusively. Y.S. has never smoked or used recreational drugs. She drinks one or two “Cosmos” on weekends.

Y.S. recently read about hemochromatosis in a textbook and wants to know if she should be tested. She has no signs or symptoms of hemochromatosis and no family history.

When counseling this patient, which one of the following statements is appropriate about hemochromatosis and hemochromatosis screening?

Who and When to Screen?

Deciding who to screen depends on the individual, features of the target population (e.g., prevalence of disease), and the performance of the screening intervention in question. Mass screening refers to screening of entire population groups. Selective screening refers to screening of selected high risk groups. Even when the benefits of performing a screening intervention are clear for a specific patient or target population, there may be controversies in when to initiate screening; whether to repeat screening at all; if repeat screening is warranted, how frequent and at what intervals; and when to cease screening.

The recommendations for breast cancer screening are one excellent example of this conundrum, despite the fact that breast cancer is the second leading cause of cancer for women. A mammogram for a 55 year old healthy woman may be an excellent screening test for breast cancer. A 92 year old woman with end-stage renal disease, Alzheimer’s disease, and colon cancer may not derive the same benefits from the same mammogram. There are multiple modalities for screening including breast self-examination, a clinical breast-examination, mammography, ultrasonography, magnetic resonance imaging, scintimammography, and positron-emission tomography. These modalities have varying degrees of specificity, sensitivity, reduction of morbidity and mortality, and fluctuate in the women being screened (e.g., women under 40 years of age, between 40 and 49 years of age, between 50 and 74 years of age or 75 years of age and older; women with average or high breast cancer risk factors; women with denser breasts; women with genetic BRCA1 and BRCA2 defects, etc.). In 2009 the USPSTF summarized their recommendations for breast cancer screening for U.S. women based on available evidence:

| Summary of USPSTF 2009 Recommendations for Breast Cancer Screening |

|---|

|

The specific USPSTF grading definitions will be covered later in this module.

| << Chemoprophylaxis |