Physician skills in prevention and management of complications of diabetes are paramount. The goal is to reduce morbidity and mortality and to reduce the direct and indirect cost on individuals, their families, and to local, national, and global resources.

Cardiovascular Disease

The major cause of mortality in diabetic patients is cardiovascular disease. It is also the major cause of morbidity, and direct and indirect costs. Type 2 diabetes is an independent risk factor for macrovascular disease, and its common co-existing conditions in metabolic syndrome are also risk factors. Physicians should be aware of the signs and symptoms of cardiovascular disease and should make every effort, along with the patient, to reduce these risk factors. Substantial benefits have been seen when multiple risk factors are addressed together, with evidence of improvements in 10-year cardiovascular risk among diabetic patients in the U.S. during the first decade of the 21st century.

Hypertension

Screening and Diagnosis

Blood pressure should be taken on diabetic patients at every clinic visit. Patients with a blood pressure ≥140 mmHg or a diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg should have their blood pressure re-checked on a subsequent day to confirm the diagnosis of hypertension. Patients with a blood pressure of ≥120/80 should be advised on lifestyle modification to prevent hypertension.

Blood Pressure Goals in Diabetes

Blood pressure goals for diabetic patients may be lower than those for the general population (which depend on age and other risk factors according to JNC 8 guidelines). According to the 2015 ADA guidelines, patients with diabetes should have a systolic blood pressure (SBP) <140 mmHg and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) <90 mmHg.

Treatment

- Diabetic patients with frank hypertension (SBP ≥140 or DBP ≥90) should be on drug therapy along with lifestyle modifications (medical nutritional therapy and physical activity).

- In non-black diabetic patients without chronic kidney disease, first line agents include thiazide-type diuretic, calcium channel blocker (CCB), angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI) or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB). In black diabetic patients without chronic kidney disease, first line agents include thiazide-type diuretic and calcium channel blocker (CCB). In all diabetic patients regardless of race but with chronic kidney disease, an ARB or ACE inhibitor is the first line agent.

- Most diabetic patients with hypertension require more than one medication to optimize the blood pressure. One or more medications should be given at bedtime.

Hyperlipidemia

Screening

Patients with type 2 diabetes have a higher prevalence of dyslipidemias. According to ADA 2014 guidelines, in adult diabetic patients, checking a lipid panel is recommended annually.

Goals and Treatment

The ADA 2014 guidelines suggest lipid management somewhat different than the ACC / AHA 2013 guidelines, which recommended “moderate-” or “high-intensity” statins for all patients with diabetes (see hypertension and hyperlipidemia modules). Lifestyle modification, as outlined in the previous section, is recommended for all patients.

Per the ADA, statin therapy is recommended, regardless of baseline lipid level, for diabetic patients:

- With known cardiovascular disease (CVD).

- Without known CVD, but over age 40 with one or more other CVD risk factors (family history, hypertension, smoking, dyslipidemia, or albuminuria).

Per the ADA, statin therapy may be targeted towards a specific LDL level, or towards a percent reduction in LDL:

- <70 mg/dL using a high-dose statin is an option for patients with known CVD.

- <100 mg/dL in diabetic patients without known CVD.

- 30-40% less than baseline if targets above are not attainable on the maximum tolerated statin dose.

Statins are contraindicated in pregnancy. Combination therapy (adding a second agent in addition to a statin) is not recommended, as current evidence does not show any additional cardiovascular benefit in diabetic patients.

Antiplatelet Agents

Recommendations from the ADA 2014 Guidelines:

- Use aspirin therapy (75–162 mg/day) as secondary prevention for those with diabetes and a history of CVD (note: the ADA guidelines call this secondary prevention of CVD events, but in the PCORE prevention module this is classified as tertiary prevention; A recommendation).

- There is weaker evidence supporting use of aspirin for diabetic patients with >10% 10-year risk of CVD (usually men over 50 or women over 60 with at least one additional major risk factor; C recommendation).

- Aspirin should not be recommended for CVD prevention for adults with diabetes at low CVD risk (10-year CVD risk, 5%; C recommendation).

Smoking Cessation

All patients should be advised not to smoke, and counseling in smoking cessation and treatment should be integrated into all diabetes care visits.

Cardiovascular Disease Screening and Treatment

Recommendations from the ADA

- In asymptomatic diabetic patients, routine screening for CVD is not recommended. Screening does not improve outcomes over and above addressing CVD risk factors.

- Risk factors should be assessed at least annually.

- Patients with known CVD should receive aspirin and statin therapy.

- Avoid thiazolidinediones (TZDs) in symptomatic heart failure, as these agents are associated with fluid retention, and their use can be complicated by the development of CHF.

- Metformin can be continued in CHF with normal renal function, but should be discontinued in unstable or hospitalized patients with CHF.

Nephropathy Screening and Treatment

General Recommendations

Optimize glucose control and blood pressure, with as many coordinated interventions as needed, to reduce the risk or slow the progression of nephropathy. Large studies have shown a delay in onset and progression of nephropathy through intensive diabetes management.

Goals

The goal of nephropathy screening and treatment is to reduce the risk and slow the progression of nephropathy. This is done by optimizing glucose and blood pressure control. In those with any degree of chronic kidney disease, protein intake should be reduced to recommended daily allowance of 0.8 g / kg.

Screening

From the time of diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, all patients should be screened annually for urine albumin excretion >30 mg/24h, using measurement of the albumin-to-creatinine ratio in a random spot urine sample. Urine albumin screening can miss >20% of progressive disease, so serum creatinine should also be measured annually in all patients with diabetes to estimate the glomerular filtration rate. Serum creatinine should be used to estimate the GFR and stage the level of renal function.

Treatment

Which of the following treatments has been shown in controlled trials to slow progression of nephropathy in persons with type 2 diabetes and >300 mg/24 hr urine albumin excretion?

- In type 2 diabetic patients with albuminuria >300 mg/24 hr, an ACE inhibitor or ARB is recommended to delay progression or nephropathy.

- The evidence is weaker for prescribing ACE inhibitors or ARBs in patients with albuminuria 30-299 mg/24 h. There does not appear to be a role for ACE inhibitors or ARBs in primary prevention of nephropathy among diabetic patients with albuminuria < 30 mg/24 h (and normal blood pressure).

- Combination of ACE inhibitors and ARBs is not recommended. Despite greater reductions in albuminuria, there is no evidence of improvement in clinical outcomes.

- Reduction of protein intake in patients with albuminuria is not recommended due to conflicting evidence of any benefit for glycemic measures, CVD risk factors, or decline in GFR.

- ACE inhibitors and ARBs are contraindicated in pregnancy.

- Referral to a kidney specialist should be considered in cases of diagnostic uncertainty, challenging management issues, or advanced kidney disease.

- More evidence is available for ACE inhibitors for prevention of major CVD outcomes (MI, stroke, death), while more evidence is available for ARBs for prevention of ESRD.

There is a lack of evidence, so only expert consensus, on the following:

- Monitoring creatinine and potassium levels when using ACE inhibitors, ARBs, or diuretics.

- An eGFR cutoff at which to more aggressively evaluate and manage complications of CKD

- Continued monitoring of albuminuria to assess response to therapy and/or disease progression

Diabetes mellitus may not necessarily be the cause of CKD in a diabetic patient. The specific cause of CKD should be investigated fully. The term “diabetic glomerulopathy” should be reserved for biopsy-proven kidney disease caused by diabetes.

Retinopathy Screening and Treatment

General Recommendations

Optimize glucose control and blood pressure to reduce the risk or slow the progression of diabetic retinopathy. Aspirin plays no role in preventing or exacerbating diabetic retinopathy.

Screening

All patients with type 2 diabetes should have a dilated and comprehensive eye examination by an optometrist or ophthalmologist soon after the diagnosis of diabetes is made.

- If there is no evidence of retinopathy, it is reasonable to repeat the exam in 2 years.

- If retinopathy is found, exams by an optometrist or ophthalmologist should be repeated annually.

- If retinopathy is progressive, exams should be more frequent.

The presence of retinopathy is related to the duration of the diabetes.

In the context of pre-existing (not gestational) diabetes, women planning to be or currently pregnant should:

- Receive counseling on the risk of development or progression of retinopathy during pregnancy.

- Have a comprehensive eye exam during the first trimester with “close follow-up” until a year postpartum.

- Women who develop gestational diabetes are not at increased risk for diabetic retinopathy (Fong, 2003).

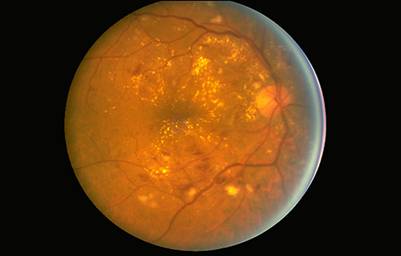

Non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy

Proliferative diabetic retinopathy

Patients with macular edema, severe non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy, or proliferative retinopathy require referral to an experienced ophthalmologist for treatment.

Laser photocoagulation for diabetic retinopathy reduces the risk of vision loss, but the treatment usually does not restore lost vision.

In the presence of macular edema, anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) therapy improves vision and reduces the need for laser treatment.

Aspirin provides no benefit with respect to retinopathy, but also has no negative impact on retinopathy if it is required for cardiovascular disease or other medical indications.

Neuropathy Screening and Treatment

Diabetic Autonomic Neuropathy

The role for autonomic neuropathy screening is unclear: it can aid in risk stratification, but there is no specific treatment prior to onset of signs and symptoms, aside from glycemic control. Major clinical manifestations of diabetic autonomic neuropathy include exercise intolerance, constipation, gastroparesis, erectile dysfunction, sudomotor dysfunction, impaired neurovascular function, and hypoglycemic autonomic failure.

The cardiac form of diabetic autonomic neuropathy (CAN) is an independent predictor of cardiovascular mortality, and can be detected early using a deep-breathing reflex testing, with later signs including resting tachycardia and orthostasis.

Treatment of diabetic autonomic neuropathy includes metoclopramide for gastroparesis and the use of bladder and erectile dysfunction medications.

Screening and Diagnosis: Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy

All patients should be screened for distal symmetric polyneuropathy (DPN) at diagnosis and at least annually thereafter, due to potential complications described below in the section on foot care. Screening can be done in the primary care clinical setting using a 10-g monofilament for light touch, pin-prick sensation, a 128-Hz tuning fork for vibration, and a hammer for ankle reflex. The combination of more than one test has a sensitivity of more than >87%. Testing should begin at the dorsal surface of the great toes proximal to the nail beds, and proceed proximally to determine the extent of neuropathy. Other diagnoses should be considered in patients with severe or atypical neuropathy.

Treatment: Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy

Symptomatic treatment of DPN begins, as with most complications of diabetes, by optimizing glucose control. This can modestly slow progression but not reverse neuronal loss. Pain relief from medications is partial at best. There is limited comparative effectiveness data available on the wide range of medications used for neuropathic pain (e.g. seizure medications, anti-depressants, and opioids). Only 2 recently patented medications have been studied specifically FDA-approved for diabetic neuropathy. Not surprisingly, they are much more expensive versions of similar generic options in the same class that were not specifically FDA-approved for diabetic neuropathy.

Diabetic Foot Care

Recommendations from the ADA

Amputation and foot ulceration, arising from diabetic neuropathy and/or PAD, are common and major causes of morbidity in people with diabetes.

Strong evidence supports:

- A comprehensive foot examination performed annually to identify risk factors predictive of ulcers and amputations. The foot examination can be accomplished in a primary care setting and should include visual inspection, palpation of pulses, and loss of protective sensation testing (see above).

- A multidisciplinary approach for individuals with foot ulcers and high-risk feet, especially those with a history of prior ulcer or amputation.

- General foot self-care education for all patients with diabetes.

Weaker evidence supports:

- Referral to foot care specialists for ongoing preventive care and life-long surveillance for patients who smoke or have had prior lower-extremity complications.

- Initial screening for peripheral arterial disease (PAD), including asking about symptoms of claudication, assessing the pedal pulses, and possibly an ankle-brachial index (ABI) for asymptomatic PAD.

- For patients with significant claudication or a positive ABI,

- referral for further vascular assessment and

- exercise, medications, and surgical options.

Early recognition and management of independent risk factors can prevent or delay adverse outcomes. The risk of ulcers or amputations is increased in people with the following risk factors:

- Peripheral neuropathy with loss of protective sensation.

- Foot deformity.

- Peripheral vascular disease (decreased or absent pedal pulses).

- A history of ulcers or amputation.

- Visual impairment.

- Diabetic nephropathy or ESRD.

- Poor glycemic control.

- Cigarette smoking.

Immunizations in Diabetic Patients

Influenza and pneumonia are preventable infectious diseases associated with a high morbidity and mortality in the elderly and people with chronic diseases. The evidence is weaker specifically for patients with type 2 diabetes, but they should be offered:

- Annual influenza vaccination.

- Adults aged 19 through 64 years with diabetes mellitus: administer PPSV23. At age ≥65 years, administer PCV13 at least 1 year after PPSV23, followed by another dose of PPSV23 at least 1 year after PCV13 and at least 5 years after the last dose of PPSV23.

- Hepatitis vaccination if aged 19-59, and possibly if aged 60 or older.

Diabetes at a Glance

Don’t feel overwhelmed! It is a lot of information but now you are armed with the latest information about the prevention, diagnosis, and management of type 2 diabetes. An executive summary of the 2014 guidelines is available here, and an online quick-reference guide to the guidelines is also available. A summary of revisions made in 2015 is available here.

| << Other Injectable Agents |