Assessing Glycemic Control

Patients and providers have 2 main tools to assess the effectiveness of the management plan: self-monitoring blood glucose numbers and A1C testing.

Self-Monitoring of Blood Glucose

Frequency and timing of blood glucose monitoring depends on several factors. Here are general rules of thumb for glucose monitoring:

- Routine monitoring is not necessary for patients who are on oral agents and have A1C at goal. However, you may see that many patients find reassurance through daily monitoring their glucose even though their doctor no longer recommends the practice.

- Morning fasting sugar (before breakfast) is typically the most helpful starting data point for patients whose A1C is high. If the A1C is high, titrate oral or insulin therapy until the fasting pre-breakfast glucose is <130 mg/dl).

- If A1C remains above goal with fasting pre-breakfast at goal in a patient on any regimen, test before and 2 hours after the main meal of the day. This can detect post prandial glucose excursions, which can be lowered through diet or medication changes.

And if the patient is on insulin:

- Monitor pre-breakfast glucose daily.

- Monitor as directed for meal-time insulin adminstration

- Test before exercise; before critical tasks like driving; or when glucose is suspected to be low

All patients should have their self-monitored blood glucose skills reassessed periodically, especially if the glucometer numbers do not correspond to HgA1C levels.

HgbA1C Testing

The A1C test measures a patient’s average glycemic levels over the past two to three months. Hemoglobin A1C in people without diabetes is between 4 – 5.6%, which means that 4 – 5.6% of a non-diabetic person’s hemoglobin has non-enzymatically attached glucose. In a chronically uncontrolled diabetic patient, the percentage of hemoglobin that has non-enzymatically attached glucose is much higher. The test is a way of assessing glycemic control at initial diagnosis and ongoing continuity of care.

Glycemic Targets

The American Diabetes Association recommends targets for A1C and self-monitored blood glucose levels, depending on the patient’s individual profile:

- A reasonable hemoglobin A1C for many non-pregnant diabetic patients in general <7%.

- A more stringent hemoglobin A1C goal (<6.5%) might be reasonable for some patients (e.g. those with long life expectancy, short duration of diabetes, no significant CVD), if significant hypoglycemia or other side effects can be avoided, but this is based on weaker evidence.

- A less stringent A1C (<8%) may be considered in patients with histories of severe hypoglycemia, limited life expectancies, advanced diabetes complications, extensive comorbid conditions, and in those with longstanding diabetes in whom the general goal is difficult to attain despite multidisciplinary efforts.

- Pre-meal capillary glucose of 90 – 130 mg/dL.

- Post-meal (1 – 2 hours) capillary glucose of <180 mg/dL.

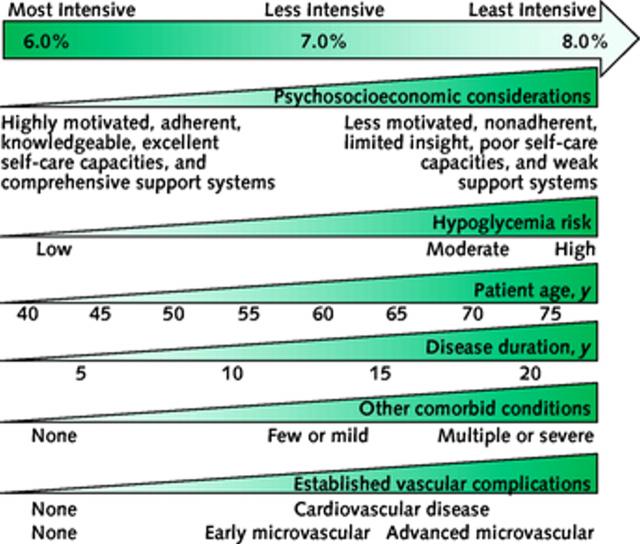

A schematic framework to determine glycemic goals for your particular patient:

Above is a depiction of the elements of decision making used to determine appropriate efforts to achieve glycemic targets, as suggested by Ismail-Beigi et al in 2011 and adopted by the ADA in their 2014 guidelines. “Characteristics and predicaments toward the left justify more stringent efforts to lower A1C, whereas those toward the right are compatible with less stringent efforts. Where possible, such decisions should be made in conjunction with the patient, reflecting his or her preferences, needs, and values. This ‘scale’ is not designed to be applied rigidly but to be used as a broad construct to help guide clinical decisions.” Ismail-Beigi et al; ADA Standards of care in Diabetes–2014).

| << Patient Education |