Individual and Social Determinants of Health in Chronic Illness

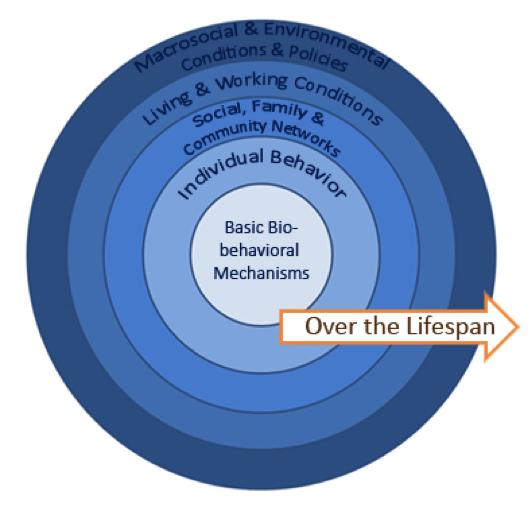

There are many preventable factors that contribute to the leading causes of death and disability: economic and educational disparities; public policy; environments that do not promote health; poor delivery of clinical and community preventive services; and unhealthy behaviors and other lifestyle risk factors. When assessing preventive and treatment strategies, it is useful to consider a socio-ecologic framework that posits that behaviors and health are influenced over the life span at “multiple levels from the individual to families to larger systems and groups and then more broadly to populations and the ecosystem” (Stokols, 1996).

The therapeutic lifestyle changes needed to manage chronic illnesses like diabetes, hyperlipidemia and hypertension are often most effectively targeted at multiple levels simultaneously–individual, provider, family or social, and community. For example, a multi-level, patent-centered plan for your 58 year-old uninsured patient with an elevated (38%) 10-year cardiovascular risk could include:

- Individualized diet counseling incorporating culturally appropriate foods to lower blood cholesterol

- Specific, realistic approaches to integrating exercise into his everyday life

- Advice targeted to his knowledge base on tobacco dangers

- Affordable generic drug regimen created with PMD

- Community evening classes for aerobic classes at the local school

- Advertising on buses about healthy diets

- State tobacco tax

Convened by the CDC, the Community Task Force (CTF) assesses and makes evidence-based recommendations in its Community Guide for effective prevention strategies at the community or population level. Integrating recommendations from USPSTF and CTF fits nicely with the socio-ecologic model. Using multiple strategies at interrelated levels yields optimal individual and community health outcomes.

A good example of integrated initiatives is tobacco control: “Optimal success in reducing tobacco-use prevalence has occurred when, in addition to clinical services, community-level interventions…have been made accessible and available” (Ockene, 2007). The USPSTF recommends screening all adults in clinical settings for tobacco use and providing cessation interventions. Clinicians should screen all pregnant women and provide pregnancy-tailored counseling and interventions. The CTF recommends several community preventive services, including banning or restricting smoking in public or work places, increasing tobacco prices, launching media campaigns, reducing patient costs for smoking cessation regimens, and deploying telephone quitter support.

Although difficult to measure, direct evidence is emerging around the superiority of combined clinical and community interventions. One study compared approaches to juvenile offenders with substance use disorders. Compared to traditional family court, combined implementation of a dedicated juvenile drug court, group support, and intensive individual counseling reduced alcohol, marijuana, and poly-drug use more than implementation of drug court alone (Henggeler et al, 2006).

Individual determinants: the patient’s perspective

Patients’ ideas about health and illness should never be assumed to be synonymous with sociocultural background. A provider taking time to assess the patient’s understanding (or explanatory model) of their illness will arrive at more effective collaboration with the patient (Kleinman et. al 1978). Patient non-adherence can often be traced back to misunderstanding, poor communication, and the physician’s lack of awareness about the patient’s understanding, hopes, confidence, expectations and fears about disease and treatment. Arriving at a shared understanding with your patient on disease and treatment has been shown to improve patient outcomes, avoid unnecessary testing, and lead to better understanding between you and your patient (Street et al 2008). Get to know your patient – it’s good for both of you.

|

Avoiding Assumptions “The physician serves as the expert on disease, whereas the patient experiences a unique illness. Even when the patient’s and the physician’s socio-cultural backgrounds are similar, substantial differences may exist because of these separate perspectives.” Carrillo et al,1999 |

Social determinants: the patient’s world

Health is determined in part by access to social and economic opportunities; the resources and supports available in neighborhoods, and communities; the quality of schooling; the safety of workplaces; the cleanliness of water, food, and air; and the nature of social interactions and relationships. To ensure that all Americans have an equal opportunity to make the choices that lead to good health, advances are needed not only in health care but also in the fields of education, childcare, housing, business, law, media, community planning, transportation, and agriculture. One of the four overarching goals for the decade of Healthy People 20201 is to “create social and physical environments that promote good health for all.” This emphasis is shared by the Institute of Medicine, World Health Organization, US National Partnership for Action to End Health Disparities3 and the National Prevention and Health Promotion Strategy.

Social determinants of health are conditions in the environments in which people are born, live, learn, work, play, worship, and age that affect a wide range of health, functioning, and quality-of-life outcomes. Conditions (e.g., social, economic, and physical) in these various environments and settings (e.g., school, church, workplace, and neighborhood) have been referred to as “place.”5 In addition to the more material attributes of “place,” patterns of social engagement and sense of security and well-being are also affected by where people live. Resources that enhance quality of life can have a significant influence on population health outcomes. Examples of these resources include safe and affordable housing, access to education, public safety, availability of healthy foods, local emergency/health services, and environments free of life-threatening toxins. Understanding the relationship between how population groups experience “place” and the impact of “place” on health is fundamental to the social determinants of health—including both social and physical determinants.

Examples of social determinants:

- Resource availability (e.g., safe housing, food markets)

- Access to educational, economic, and job opportunities

- Access to health care services

- Quality of education and job training

- Recreation and leisure-time resources

- Transportation options

- Public safety

- Social support

- Social attitudes (e.g., racism, distrust of government)

- Exposure to social disorder (e.g., presence of trash; lack of community cooperation, incarceration of community members)

- Socioeconomic conditions (e.g., concentrated poverty)

- Residential segregation

- Language/Literacy

- Access to mass media and emerging technologies (e.g., cell phones, Internet, social media)

- Culture

Examples of physical determinants:

- Natural environment, such as green space (e.g., trees, grass) or weather (e.g., climate change)

- Built environment, such as buildings, sidewalks, bike lanes, and roads

- Worksites, schools, and recreational settings

- Housing and community design

- Exposure to toxic substances and other physical hazards

- Physical barriers, especially for people with disabilities

- Aesthetic elements (e.g., good lighting, trees, and benches)

By working to establish policies that positively influence social and economic conditions and those that support changes in individual behavior, we can improve health for large numbers of people in ways that can be sustained over time. Improving the conditions in which patients live, learn, work, and play will create a healthier population, society, and workforce.

Healthy People 2020 proposes a place-based organizing framework, reflecting 5 key areas of social determinants of health (SDOH):

- Economic Stability includes poverty, employment, food security, housing stability

- Education incudes high school graduation rates, enrollment in higher education, language and literacy, early childhood education and development

- Social and Community Context include social cohesion, civic participation, perceptions of discrimination and equity, incarceration/institutionalization

- Health and Health Care includes access to primary and specialty health care and health literacy

- Neighborhood and Built Environment incudes access to healthy foods, quality of housing, crime and violence, environmental conditions

| New York City is a city of neighborhoods. Their diversity, rich history and people are what make this city so special.

Our communities are not simply made up of individual behaviors, but are dynamic places where individuals interact with each other, with their immediate environments and with the policies that shape those environments. The Community Health Profiles include indicators that reflect a broad set of conditions that impact health. Our hope is that you will use the data and information in these Community Health Profiles to advocate for your neighborhoods. — Dr. Mary Bassett MD, MPH. 2015 Commissioner, New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene |

Data Gathering: community

An individual provider must be aware of the community forces acting on patient health outside of the exam room. Providers working in NYC are fortunate to have the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene tracking data from New Yorkers annually on health status and many social determinants of health. Annual Community Health Profile reports are available publicly, on this NYC DOHMH website for approximately 60 separate neighborhoods. For example, the 2015 Community Health Profile for Washington Heights contrasts the health status of residents of Washington Heights/Inwood with the rest of Manhattan and NYC: http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/downloads/pdf/data/2015chp-mn12.pdf

Data Gathering: patient

Patients come to their doctor’s office with certain beliefs, concerns, and expectations about their illnesses and health, which may be influenced by culture, socioeconomic status, education level, and previous experiences with the medical system.

In order to provide specific and tailored education and support, a physician must assess and understand the patient’s socio-cultural background and how it affects their health beliefs and individual behaviors. This can improve clinical diagnosis and management, promote culturally responsive health education, avoid unnecessary medical testing, and lead to better understanding between you and your patients. Weiner et al (2010) and others have demonstrated clearly that inattention to sociocultural context leads to more errors in decision-making by physicians. There is growing evidence that there may be economic benefit as well (Commonwealth Fund, 2014).

One excellent patient-centered tool used by physicians, medical students, residents and other providers with patients is this set of questions exploring the patient explanatory model and socio-cultural background (Carrillo et al,1999).

- Enhance provider understanding about the patient’s challenges (e.g.socio-economic, or cultural) impacting their health

- Elicit a patient’s explanatory model for an illness or health issue, including how in control they feel of their health

- Help providers feeling confused, or stuck in clinical inertia.

- Allow providers to support their patient’s points of resilience.

Additional Resources on Social Determinants of Health

CDC Social Determinants of Health

Secretary’s Advisory Committee Social Determinants of Health Report

Bibliography:

Downs JR, O’Malley PG. Management of Dyslipidemia for Cardiovascular Disease Risk Reduction: Synopsis of the 2014 U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and U.S. Department of Defense Clinical Practice Guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(4):291-297.

Hayward RA, Krumholz, HM. Three Reasons to Abandon Low-Density Lipoprotein Targets. An Open Letter to the Adult Treatment Panel IV of the National Institutes of Health. Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes; 2012; 5: 2-5. http://circoutcomes.ahajournals.org/content/5/1/2.long

Cannon et al, Ezetimibe Added to Statin Therapy after Acute Coronary Syndromes N Engl J Med 2015; 372:2387-2397. IMPROVE-IT NEJMJune 18 2015. http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1410489

Everett BM, Smith RJ, Hiatt WR. Reducing LDL with PCSK9 Inhibitors — The Clinical Benefit of Lipid Drugs. NEJM. 2015; 373:1588-1591.

DeFilippi et al. An Analysis of Calibration and Discrimination Among Multiple Cardiovascular Risk Scores in a Modern Multiethnic Cohort, Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(4):266-275

Street RL et al. How does communication heal?: Pathways linking clinician–patient communication to health outcomes. PEC 2009, 74 : 295–301

Weston WW, Brown JB, Stewart MA. Patient-Centered Interviewing Part I: Understanding Patients’ Experiences. Can Fam Physician 1988. 35:147–151

| << Evolving Evidence, Conflicting Interpretations |