Hi folks!

Hope you had a great Spring break. I thought I should post my presentation slides on this blog, for the benefit of those who weren’t around during our session last week or might find it handy to have a soft copy of the slides!

The gist of my presentation is as follows:

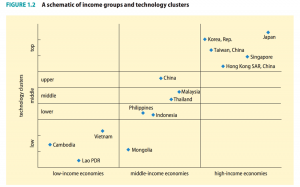

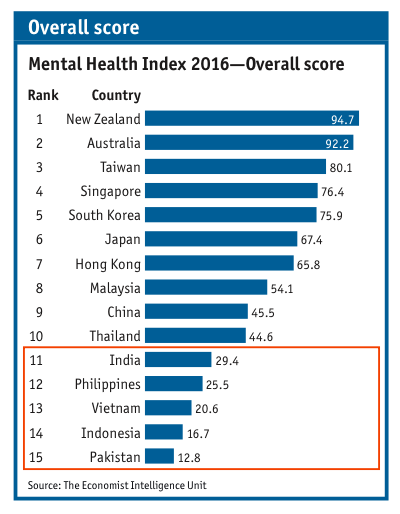

- On 07 November 2016, Singapore’s Deputy Prime Minister Mr. Tharman Shanmugaratnam announced that the Ministry of Education will spend SGD$350 million (equivalent to USD$250 million) on social science and humanities research for the next five years.

- The government will also establish Singapore’s very first Social Science Research Council, while establishing partnerships with existing institutes in the US such as the SSRC in Brooklyn and Centre for Advanced Study in the Behavioural Sciences at Stanford.

- My presentation examines the implications and limitations of these newly implemented government policies, focusing particularly on the potential winners and losers of these reforms, in HE institutions and the wider society.

Please feel free to share with me your thoughts or questions on this recent government reform! Will look to hear from you, specially on how we might be able to address critics’ skepticism towards the huge amount of funding that is channelled into this project by the Singapore government (while governments in other parts of the world such as the Trump administration is trying to cut back heavily on funding for the arts and cultural expression), fair democratic representation of members in the SSRC (because right now it is predominantly made up of senior academics and civil servants) and conflict between the winners and losers of this reform. Thank you!

– Tim