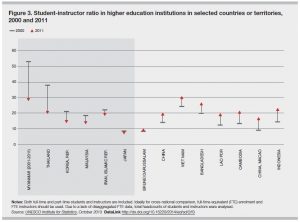

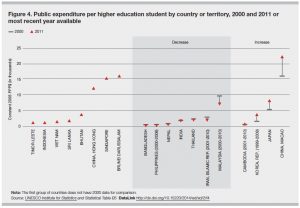

Last week we looked at some indicators of Higher Education access across South Asian countries that elicited some very interesting discussion. This week, we mined some more data from UNESCO’s Institute of Statistics on higher education quality across the South Asian countries. Coincidentally, it ties it neatly with this week’s News post on the newly released Times HE Rankings! Below are some infographics on the student-instructor ratios, public HE expenditure per student and academic rankings across South Asian countries.

Quality of higher education is tough to measure and these indicators are far from perfect. What other information would you like to have on HE quality in other countries? Do you think that it is fair to apply the same normative criteria of ‘good quality’ for developed nations and for developing economies? What are the the benefits for South Asian nations in chasing these quality targets?

Source: Higher Education in Asia: Expanding Out, Expanding Up (http://www.uis.unesco.org/

Thank you Soumya for great information! I agree with Tim with what struck me the most. Its interesting to see how teacher-student ratio has increased in the last years in some South Asian countries, I’m curious to see why this happened, is there any reason apart from a growing youth population or increasing enrollment rates, and if the governments are concerned by this. It is ideal to have smaller classes so students receive more attention, so how will they tackle this potential threat?

Additionally, I am intrigued by your question on how to assess developing versus developed countries. Coming from Mexico, the quality of higher education is far from ideal, and working to improve is hard without having a benchmark that is achievable.

Angelica, that’s a good question. Most South Asian countries have been trying to increase their GER or gross enrollment in higher education. I suppose it is taking longer for them to hire more instructors, or in some cases, it is taking longer for the national education system to produce enough PhDs to fill the faculty positions created. Hence, in the short or medium term, the ratio may worsen before it improves. Since Instructor-Student ratio is a widely cited statistic, the countries must be under pressure to improve this number, and I assume that most of them are trying to do so. I can only speak confidently about India, where this statistic is a concern and the government has been trying hard to fill up open faculty positions and create new ones. They are trying to incentivize universities to ramp up hiring and withholding funds in case faculty ratios are higher a certain level. But the country faces a massive brain-drain issue and getting good quality faculty to return to India is a challenge.

While this is a great effort, I am afraid that chasing numbers based on western nations makes the quest for quality myopic. An input-focused culture driven by statistics without any attention on the processes or outputs, can be a pointless race for developing countries. If developing nations wish to actually improve their education quality, they have to think of ingenuous ways of providing more resources for their students and also making more of the few resources they do have. Perhaps a new paradigm for “nationally relevant quality” needs to be developed where the focus should be on making students able enough to understand their local context and solve their local problems, instead of competing with developed nations in fields that provide little benefit to the country itself. Other than this generic statement, I don’t have an answer for the question I posed 🙂

I am not sure if it is possible for developing countries to distance themselves from the pressure of following the same quality norms as other nations. As we keep reading, it is a globalized sector after all!

Thank you Soumya for sharing these fascinating statistics! I am particularly interested in the changes in student-instructor ratio across different countries from 2000 and 2011. It appears that higher institutions in most geographically Asian countries are moving towards an ideal ratio of 10 to 25 students per instructor. Student-instructor ratio is definitely one effective indicator of HE quality across countries, as it reveals the degree of intellectual access and attention that a student might receive from their instructor. I’m curious to know why 10-25 seems to be the unanimous range that these countries are veering towards. And I also think that the student-instructor ratio really depends on factors such as the mode of instruction (lecture vs. seminar vs laboratory or field work) and the nature of each discipline.

Hailing from a Humanities undergraduate background, I can attest to the fact that roughly 10 students to 1 instructor is an ideal ratio for a seminar that seeks to encourage a free exchange of ideas, and where students may feel more compelled to articulate their views and engage with one another’s points, because they are unable to be silent and fade into the crowd, which can be the case in comparatively larger classes. However, I can see why the same ratio might not be as ideal for say, a Physics or Math tutorial that does not necessarily require active intellectual debate in class, but rather a direct application of mathematical formulae or scientific concepts as a means of learning. Hence the ratio given by UNESCO is perhaps too broad a measurement and does not accurately indicate HE quality across disciplines.

Hi Tim,

Thanks for your comment. I agree that the 1:25 ratio is slightly arbitrary. I believe that this is a Western norm, possibly can be traced to Oxbridge and old Northeastern universities where 20 gentleman took classes with one professor. While this is a round figure, as you mentioned, it varies a lot even in western universities depending upon the level of study and kind of college. But it does give an approximate idea about the relative size of the teaching body and student body. If this ratio is too large across the country (like Myanmar or Thailand), then it is probably indicative of faculty shortages throughout the country which will impact quality. I suppose we must also be aware that the style of instruction in Asian institutions can vary a lot from those in Europe and US. Critical thinking, production of original work or thought and developing the student’s voice are important aspects of quality education in the western system. In Asian countries, the instruction may be top-down or based on regurgitating facts, such instruction does not require small classrooms. You are also right in thinking that these ratios differ by subject areas. STEM fields can probably produce great students with fewer teachers than liberal arts, critical thinking can is also less politically-charged in these fields than in liberal arts. Thus, encouraging STEM fields may be easier and politically stable than encouraging political science or sociology. An interesting thing would be to see in which kind of fields have publications by Asian researchers increased the most? Are these fields that are less politically/socially oriented and more analytical?

My sense is that these intangible but very crucial aspects of quality like critical thinking get little attention from Asian policymakers. Instead, they will concentrate on the making sure that more teachers are hired and the instructor-student ratio reported to UIS or their citizens is better. It is easier to do that than to tackle quality from the point of view of institutional culture and pedagogical reform. It is a quick and visible achievement with little political backlash!

I must add, I don’t mean to lump all Asian countries together. I know that China/India/Thailand are very different, politically, socially and educationally from Japan/South Korea, and other countries lie somewhere in this mix. But they are probably more like each other than they are like the western education systems.