Javier del Barco, a Senior Research Fellow at the Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Cientificas (CSIC) in Madrid, has just completed three months of work on Footprints collection in the Archbishop Marsh’s Library in Dublin. Below, Dr. del Barco shares just one example of some of the discoveries he made in the course of his work in Dublin.

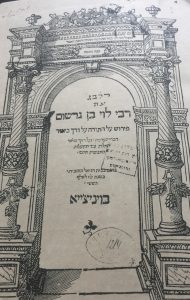

Hebrew books were subjected to censorship in Italy during the 16th and the 17th centuries. Censors’ signatures can be found in many books—both manuscript and printed—that circulated there, especially during the second half of the 16th century and the beginning of the 17th. Interestingly, these censors’ footprints enable us to follow the itineraries of the books by indirectly providing clues of the places where they were censored. One good example is Marsh’s Library’s copy of Levi ben Gershom’s (1288-1344) Milḥamot ha-Shem printed in Riva di Trento in 1560 (1)

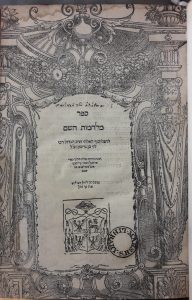

Books printed in Riva di Trento are particularly interesting and important  because the Hebrew press run there by Jacob Marcaria operated for only four years (1558-1562) and produced some 35 titles. Marcaria, who was both dayyan (judge) and physician in Cremona, established the printing press in Riva in collaboration with Joseph ben Nathan Ottolenghi, the famous rabbi of Cremona, and under the auspices and protection of Cardinal Cristoforo Madruzzo, bishop of Trento. (2) In fact, Madruzzo’s coat-of-arms appears in some of the Riva di Trento Hebrew books, as is the case with this copy of Milḥamot ha-Shem (see title page, right).

because the Hebrew press run there by Jacob Marcaria operated for only four years (1558-1562) and produced some 35 titles. Marcaria, who was both dayyan (judge) and physician in Cremona, established the printing press in Riva in collaboration with Joseph ben Nathan Ottolenghi, the famous rabbi of Cremona, and under the auspices and protection of Cardinal Cristoforo Madruzzo, bishop of Trento. (2) In fact, Madruzzo’s coat-of-arms appears in some of the Riva di Trento Hebrew books, as is the case with this copy of Milḥamot ha-Shem (see title page, right).

Printing Milḥamot ha-Shem was a very important achievement. This text includes Levi ben Gershom’s major work containing an almost complete system of philosophy and theology in which he relied on his predecessors—such as Aristotle, Averroes, Avicenna and Maimonides—and also gave his own theory. The work had circulated widely in manuscript copies, but its 1560 publication was the first time that it was ever printed, even if imperfectly. No further editions of the work were printed for over three centuries, until a new edition was published in Leipzig in 1863, probably due to the fact that understanding Milḥamot ha-Shem is not possible unless one is familiar with Levi ben Gershom’s commentaries on Averroes and the Bible.

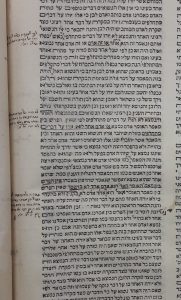

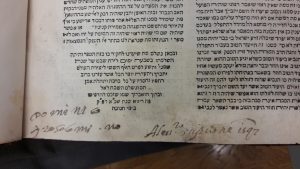

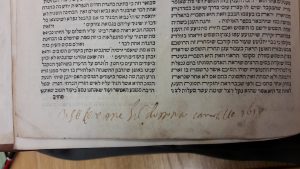

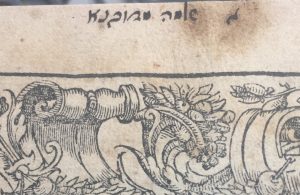

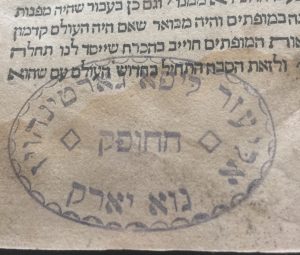

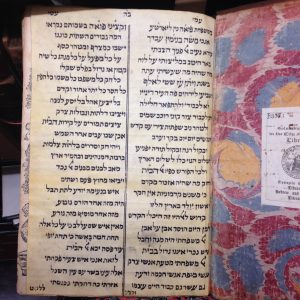

The copy in Marsh’s library was read and studied by an unknown Jewish reader, who annotated it in the margins using a semi-cursive handwritten Ashkenazi script (see image #2, left). Most noteworthy, at the end of the work we find the signatures of three different censors. In the last page, we read “Dominico Irosolomi.no”, “Aless.ro scipione 1597” (see image #3, below) and, in the previous page, “visto per me Gio domenico carretto 1618” (see image #4, below).

From this single book copy can learn much about not only the reading habits of Jews, but the censorship regime of the Counter-Reformation Catholic Church in Italy in the late sixteenth century.  The well-known Domenico Irosolimitano worked with Alessandro Scipione and Laurentius Franguellus, all of them apostates, in the Mantuan censorship commission from 1595 to 1597, the latter being replaced in 1597 by Luigi da Bologna. This commission was appointed by the bishop of Mantua and started to work in August 1595.

The well-known Domenico Irosolimitano worked with Alessandro Scipione and Laurentius Franguellus, all of them apostates, in the Mantuan censorship commission from 1595 to 1597, the latter being replaced in 1597 by Luigi da Bologna. This commission was appointed by the bishop of Mantua and started to work in August 1595.  As Popper states, “the Jews soon crowded to the building [of the Inquisition, where the commission worked] in great numbers, bringing their books with them, and carrying them away as soon as expurgated” (3). Even if Popper’s assessment should be considered with caution as far as the willingness of bringing books to the commission is concerned, it is a fact that Jews took their books to be censored in great numbers, probably in fear of the penalty for having uncensored books in their possession. After looking at the books and censoring them accordingly, censors would sign at the end of the book and add the date to their signatures, as Scipione did in this copy, but not Irosolimitano. This leads Popper to suggest that “Irosolimitano was probably at the head of the commission” (4) because “the chief censor often omitted even a date” (5). Thus Irosolimitano’s and Scipione’s signatures together and the latter’s addition of the date—1597—leaves no doubt that this copy of Milḥamot ha-Shem was under the scrutiny of the Mantuan commission in 1597.

As Popper states, “the Jews soon crowded to the building [of the Inquisition, where the commission worked] in great numbers, bringing their books with them, and carrying them away as soon as expurgated” (3). Even if Popper’s assessment should be considered with caution as far as the willingness of bringing books to the commission is concerned, it is a fact that Jews took their books to be censored in great numbers, probably in fear of the penalty for having uncensored books in their possession. After looking at the books and censoring them accordingly, censors would sign at the end of the book and add the date to their signatures, as Scipione did in this copy, but not Irosolimitano. This leads Popper to suggest that “Irosolimitano was probably at the head of the commission” (4) because “the chief censor often omitted even a date” (5). Thus Irosolimitano’s and Scipione’s signatures together and the latter’s addition of the date—1597—leaves no doubt that this copy of Milḥamot ha-Shem was under the scrutiny of the Mantuan commission in 1597.

Yet, bearing a censor’s signature did not free the book’s owner from the obligation of bringing the book to subsequent censorship commissions. This is the case with this copy, as attested by the signature of Giovanni Domenico Carretto dated to 1618, who worked censoring Hebrew books also in Mantua from 1617 to 1619 (Popper, 142). This footprint then situates this copy in Mantua still in 1618, where it had probably been since 1597 or earlier.

The book arrived in Dublin thanks to the collection activities of Archbishop Marsh (1638-1713). Marsh began collecting Hebrew books upon his arrival in Oxford in the middle of the 17th century. By 1679 he had relocated to Dublin, having been appointed provost of Trinity college, but he continued to expand his collection until his death in 1713. In most of his Hebrew books he wrote his Greek motto in the title page, as can be seen also in the title page of this copy, and in some cases, he also added a date. When the indicated year predates 1679, we can be almost certain that he acquired the book in Oxford, but if no year is indicated, we cannot be sure of the place of acquisition. As this copy of Levi ben Gershon’s Milḥamot ha-Shem has no specific date after Marsh’s motto, it could have been acquired by Marsh at any moment during his adult life, either in England or in Ireland.

From Riva di Trento and Mantua to Dublin in Ireland, probably by way of England or Amsterdam, this book teaches us about significant cultural and social aspects to consider when looking at early modern Hebrew books. Printed in Riva di Trento by Jacob Marcaria in 1560 under the sponsorship of the bishop of Trento, this copy tells us about actual collaboration and exchange between Jews and Catholics in a cultural and intellectual endeavour such as printing books in Hebrew in Northern Italy. This was possible only before the Council of Trent was finished in 1563, as the consequences of Counter-Reformation largely affected relationships between Jews and Catholics. This can be observed very well in this book, as it was censored twice in Mantua, in 1597 and in 1618, following the establishment of censorship commissions. After that date, we don’t know exactly when and how the book reached the hands of Archbishop Marsh, journeying from Mantua to England or Ireland at some point during the 17th century, but this journey reflects very well how Hebrew books in general traveled together with their owners across all over Europe and the Mediterranean since the very start of Hebrew printing and throughout centuries, until they were definitively shelved in a library. For this copy of Levi ben Gershon’s Milḥamot ha-Shem, it was Marsh’s Library in Dublin, where it remains to this day.

(1) Shelfmark: B3.3.2

(2)R. Posner and I. Ta-Shma, The Hebrew Book: An Historical Survey (Jerusalem: Keter, 1975), chapter 5, subvoce “Riva.”

(3) W. Popper, The Censorship of Hebrew Books (New York: Ktav Publishing House, 1969), p. 77

(4) Ibid., p. 78

(5) Ibid., p. 79

Recent Comments