– Angélica Creixell

Literature has the power to transport readers to different times in the history of a country. Rather than stating facts and chronological events, authors situate and educate readers about a reality through characterization, metaphors, settings and, essentially, the plot. A novel can be a form of expression for authors to subtly, or not so subtly, protest against historic periods or governmental regimes. It can enhance higher education by teaching indirectly through narratives and imagery. Such is the case of Dai Sijie.

Born on March 2, 1954, in Putian, China, he was sent to the Sichuan Providence for his re-education during Mao’s Cultural Revolution. Afterward, he sought refuge in France and became a filmmaker. Years later trying to succeed in this form of art, he found the magic and universality of literature. In “Balzac and the Little Chinese Seamstress,” he portrays the re-education reality of two young men, Luo, and the narrator, who are sent to the countryside to learn from illiterate farmers in a semi-autobiographic novel. Together they share the hardships of their new life and then fall in love with the same girl, a seamstress. They also meet Four Eyes, another young man from the same town who has a secret trunk full of books of Western literature – banned by the Communist regime. It is through literature that they discover the meaning of love, new ideas and the power of imagination. In the novel, literature represents freedom as it gives faith to the characters to overcome any obstacle. It becomes their channel of education in the middle of the mountains.

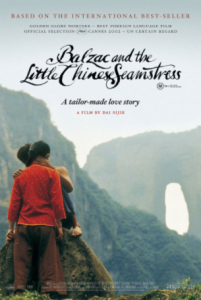

The novel’s subtle criticism was enough for it to be banned by the Chinese government. When talking about this, Dai Sijie stated, “It wasn’t that I touched the Cultural Revolution … they did not accept that Western literature could change a Chinese girl. I explained that classical literature is a universal heritage, but to no avail.” This novel about literature and love is an ode to the universality of literature and education. After its worldwide success, Dai Sijie directed the movie of the book. For me, it is one of the rare cases where the movie might be better than the book. As a filmmaker, Dai converts the novel’s simple language into beautiful images and palpable nostalgia as the two young men discover themselves in literature, Balzac, and love for the same seamstress. The film ends differently from the novel, as the two young men meet again in Beijing years later, possibly after completing graduate degrees in the United States and Europe, as did Dai Sijie with his former companions after the Cultural Revolution.

Sources and reviews:

Allen, Brooke. “A Suitcase Education.” The New York Times. Sept. 16, 2001. http://www.nytimes.com/2001/09/16/books/a-suitcase-education.html

Riding, Alan. “Artistic Odyssey: Film to Fiction to Film.” The New York Times. July 25, 2007. http://www.nytimes.com/2005/07/27/movies/MoviesFeatures/artistic-odyssey-film-to-fiction-to-film.html