by Fabrizio Quaglia

This is the first in a series of posts by Fabrizio Quaglia on his ongoing work collecting Footprints and other data from the collection of David Kaufmann, now at the Hungarian Academy of Sciences in Budapest. As Quaglia notes, the collection is multilayered, revealing libraries within libraries.

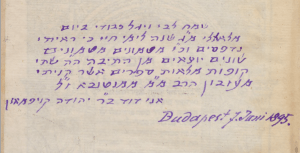

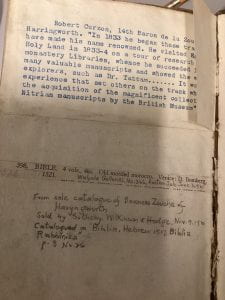

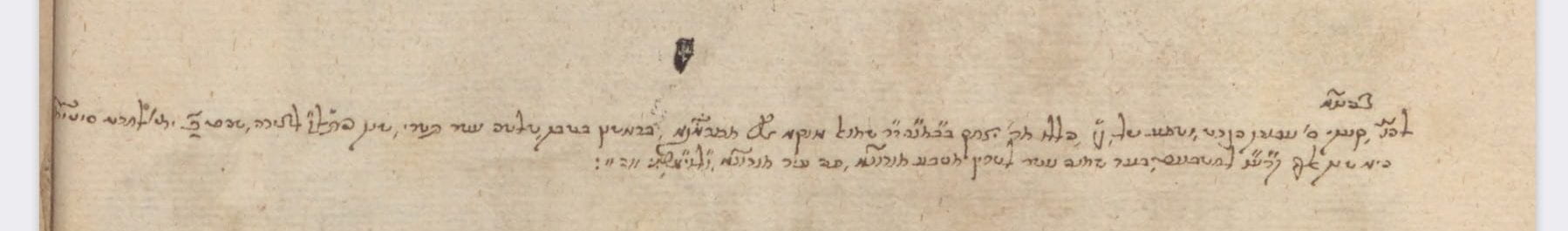

Figure 1: Emanuel Porto, Ḥoḵmatḵem we-binatḵem le-‘einei ha-‘amim = Porto astronomico, Padua 1636; verso of the front flyleaf. [Kaufmann B 288]

Italian bibliographic note by Marco Mortara about the author. Lower, David Kaufmann’s signature.

Like a traveler crossing a world of old papers, I am working on the provenance of the Hebraica and Judaica 15h-18th century volumes of the collection that belonged to the great Hebraist David Kaufmann (1852-1899) and is currently in the Hungarian Academy of Sciences in Budapest. I embarked in a journey to the past through the sources and stories that are found behind those books. Books that are not very rare or that do n

ot have a highly relevant content become interesting precisely because of the name of their distinguished collectors, some of them today forgotten by the historians while others are completely unknown to bibliographers. Occasionally I stumbled on items that are now missing (although available on microfilm), but my descriptions hopefully perhaps will permit their return.

My two-year job began in September 2022, and it is divided in two parts. The first consists of 250 books, fully digitized in REAL-R – the digital repository of the Department of Manuscripts and Rare Books and the Oriental Collection at the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. Out of 250 items, 196 show sure traces of usage, namely owners’ notes written in square and cursive Hebrew (predominantly in an Italian script) and non-Hebrew languages (Italian, German, Spanish, and Portuguese), as well as Italian and Latin signatures of Church censors, ex libris and annotations. The remaining amount has come down to us in a partial way. For example, in some cases we only have the first name of an owner, while his surname and possible place of residence have been rendered illegible. In several cases, there are anonymous glosses in the books. We have also lost information in rebinding, where flyleaves and boards might have once told us about ownership.

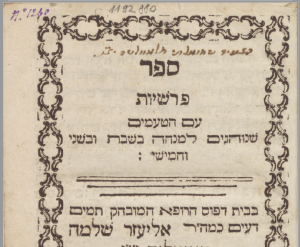

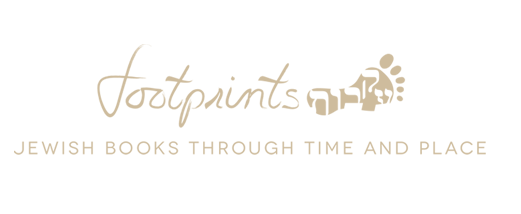

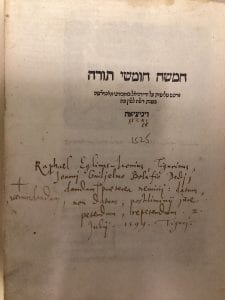

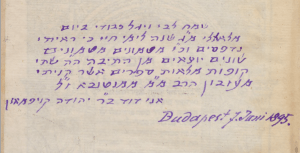

Figure 2: ‘Elleh ha-devarim, Mantua 1566, recto of the front fly-leaf. [Kaufmann B 68]

David Kaufmann’s jubilant note in Hebrew, written in Budapest on 7 June 1895 (the day of his birthday), when he saw the boxes full of books that he had bought from the estate of the recently

deceased rabbi Mortara.

In this post the focus will be on the books with the most significant provenance, where we have identified new owners that had not been found in

previous surveys of the collection. Brief biographical sketches will accompany the stories of these books on their journeys to their current home.

The Mantua Connection

Marco Mortara (1815-1894)

The historical nucleus of David Kaufmann’s collection contains books and manuscripts once owned by Marco Mortara (1815-1894), rabbi of Mantua since 1842. Kaumann purchased these books from Marco’s third son, the jurist Aristo (1857-1922). At this point 123 Kaufmann Hebrew books have been identified as from Mortara’s collection, with the distinctive printed stickers with red frame and inscription “ex libris M. Mortara” on the spine of the volumes. A few autograph owner’s notes, and often abbreviated bibliographic data in his handwriting, also reveal a Mortara origin.[1] [figure 1] Kaufmann visited Mortara’s library, one of the finest private libraries in Europe, spanning theological, literary and scientific texts, during two trips to Italy. His first visit was in the summer of 1877, when he arrived to collect the books of the Italian Jewish scholar and poet Lelio Della Torre (1805-1871) from Padua for the Rabbinical Seminary of Budapest. Kaufmann’s second visit was on April 1881, on his honeymoon with Irma Gomperz (1854-1905), the scion of wealthy Budapest family. It was a quick sale [figure 2]. Only four postcards from Mortara remain from the communications between Kaufmann and Mortara, and they are preserved in the Central Archives for the History of the Jewish People in Jerusalem (David Kaufmann, Nachträge, P 181). Three postcards were written in Hebrew and one in French, on 28 September 1883, 12 February 1884, 16 November 1884, and 7 June 1885.[2]

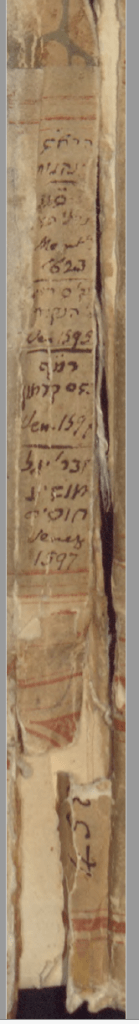

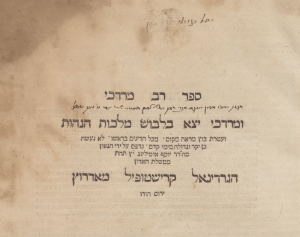

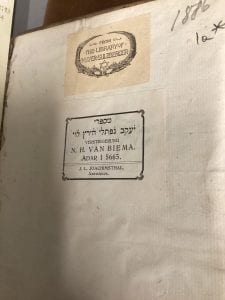

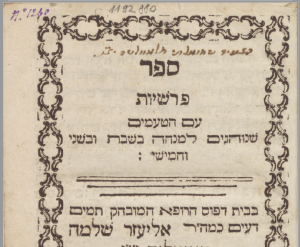

Figure 3: Sefer parašiyot ‘im ha-ṭa‘amim še-nohagim la-minḥah be-Šabbat we-be-šeni we-ḥamiši, Mantua 1679; title page. [Kaufmann B 697] Cursive Hebrew signature of the young Samuel Vita Dalla Volta.

Samuel Vita Dalla Volta (1772-1853)

Kaufmann probably knew that Mortara’s library was formed from the library of Dr. Samuel Vita Dalla Volta (1772-1853). Mortara used to point out to his illustrious Italian and foreign correspondents the importance of Dalla Volta’s collection. On 4 September 1852, Mortara wrote to his former teacher at the Rabbinical College of Padua, Samuel David Luzzatto (1800-1865), that among the volumes of S.V. Dalla Volta was a magnificent fifteenth-century undated edition (not in the Kaufmann collection) of textual and bibliographical relevance of the famous ‘Aruḵ by Natan b. Yeḥi’el (ca. 1035-1106).[3]

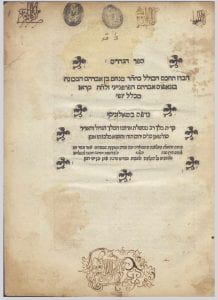

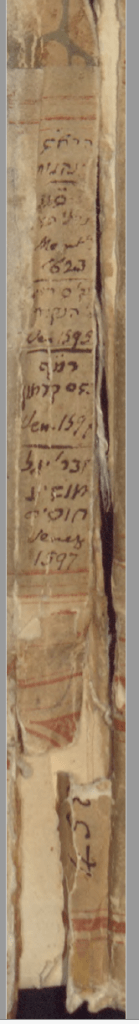

Figure 4: Natan Naṭa‘ Hannover, Yeven Meṣulah, Venice, 1653; second title page. [Kaufmann B 250]

S.V. Dalla Volta seems to have been Mortara

’s mentor and confidant. When Mortara left Viadana to continue his studies in Mantua his family entrusted him to the care of Dalla Volta (Mortara’s father, Giuseppe (1776-1853) was friendly with Dalla Volta).

[4] The very learned

[5] Dalla Volta was one of the richest Jews in Mantua.

[6] The Dalla Voltas were continually chosen among the

massari (“deputies”) who managed the ghetto.

[7] In 1823-1824 Samuel Vita was a member of the Commissione di Culto e Beneficenza della Società Israelitica, a board that governed the Jewish community of Mantua,

[8] and in that period out of 11

droghieri (“grocers”), nine were Dalla Voltas.

[9] The relationship between the young student and the older doctor and pharmacist is documented by a group of letters written when Mortara was in Padua to attend the Rabbinical College and collected in the mss. Kaufmann A 482 and A 484.

[10] Another testimony to their relationship is a dedication that Dr. Samuel Vita Dalla Volta wrote and Mortara pasted inside the front cover of his Hebrew notebook (

Zikronot), filled by Mortara between 1830s and 1870s with scholarly annotations.

[11]

Although Della Volta’s library was highly coveted by scholars like Moritz Steinschneider (1816-1907), Mortara claimed that he was able to purchase half of it (the other half was bought by the vice-rabbi of Mantua, Salomon Nissim, 1781-1864), including a good part of his estate, but since Mortara was constantly in very precarious financial straits it was more probably donated by Samuel Vita or by his widow Anna Jona (1786-1855) as a sign of gratitude and friendship.[12]

Figure 5: Mošeh b. Avraham Provinçali, Be-šem qadmon, Venice 1596; spine. [Kaufmann B 213]

Bibliographical data written by M. Mortara.

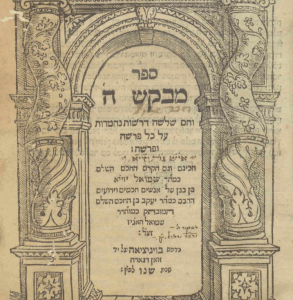

Sixty-seven books belonging to Samuel Vita Dalla Volta have been counted so far in the Kaufmann collection, among which 51 had belonged to Mortara. Aside from a few owner’s notes [figure 3], they are recognizable by S.V. Dalla Volta’s erudite glosses and by the Hebrew numerals that he wrote on the front flyleaves and/or the title pages of his volumes [figure 4]. The Hungarian rabbi and academic Solomon Marcus Schiller-Szinessy (1820-1890) stated that those numerals were library-marks.[13] But Schiller-Szinessy wrongly supposed they indicated locations of books in the library of Samuel Volta’s father, Leon Samuel Dalla Volta (1730-1801), a pharmacist and grocer and important member of the community of Mantua, since at least two books (Kaufmann B 832 and Kaufmann B 1011) were printed after his death (respectively in 1824 and 1805). After comparing the calligraphy of S.V. Dalla Volta to the mentioned Hebrew numbers, it seems reasonable to suppose that they indicate the book placements in his library, by shelf, bookcase, and book number. Their later owners – Mortara and Kaufmann – had different handwriting; in addition, Mortara inscribed his own shelf-numbers on the spines of the volumes [figure 5].

Sanson Sacerdote Modon (1679-1727)

S.V. Dalla Volta wrote that some items of his collection came from the heirs of his fellow citizen, the rabbi and poet Sanson Sacerdote (Cohen) Modon (1679-1727). This included Sacerdote Modon’s annotated Hebrew and Italian books and manuscripts, including texts in French and Spanish.[14]

The family of Sanson Cohen Modon (also Modone) was of Greek origin and since the end of the 16th century settled in Mantua, where it became one of the richest of the ghetto. Sanson obtained the lower rabbinic degree of ḥaḵam in 1721 and was nominated community scribe in 1722; he was also the secretary and chancellor of his Jewish community and member of the rabbinical court of Mantua. Sanson Cohen Modon was an important collector of Jewish books, whose traces lead to public libraries spanning three continents. Included among these books are least four Hebrew incunables and sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Hebrew books, often first editions. The Kaufmann collection holds at least six Hebrew books

Figure 6: Avraham b. Yosef ha-Levi Segal, Maseḵet megillat ta‘ani, Amsterdam 1659; title page. [Kaufmann B 426]

Cursive Hebrew signature by the young Šimšon Kohen Modon dated 28 Ṭevet 5460 [19 January 1700], and Hebrew numerals ג’ רכ”ב that should correspond to shelf-marks of S.V. Dalla Volta’s library, with overwritten Hebrew numerals.

(and around twenty manuscripts) formerly owned by

S. Sacerdote Modon [figure 6], but there are bound to be more. An excellent example of these ownerships is the

Be-šem Qadmon, Venice 1596 – a guide to the abridged rules of Hebrew grammar poetically expressed by the Talmudist Mošeh b. Avraham Provinṣali (Moisè Provenzali; 1503-1576), chief rabbi in Mantua (Kaufmann B 213; only edition) – which shows signs of use by S. Sacerdote Modon, S.V. Dalla Volta (through his father Leon Samuel), M. Mortara (and by an identified Raḥel Norṣi, probably a Rachel Norsa of Mantua).

Additional Dalla Voltas

The Kaufmann collection owns additional volumes of Mantuan origin. The rabbinical responsum of the physician of Verona Šelomoh ha-Levi, printed in Amsterdam in 1731 (Kaufmann B 975) – was acquired for one lira in 1782 by Ya‘aqov Ḥayyim mi-Lavolṭah of Mantua. He may have been the shopkeeper Jacob Vita Dalla Volta (1765-1847), son of Iseppe Benedetto Dalla Volta (1732-1809) and Ester Dalla Volta. Iseppe Benedetto was a brother of the abovementioned Leon Samuel Dalla Volta. In 1798 Jacob Vita married his cousin Rachele (1775-1847), daughter of L.S. Dalla Volta, thus becoming a brother-in-law to Dr. Samuel Vita Dalla Volta. On the title page of Kaufmann B 975 there are the deleted Hebrew numerals ‘ג’ כ’ ב that, as stated above, correspond to shelf-marks of S.V. Dalla Volta’s library (there is also the Mortara sticker with bibliographical data inscribed by him). But Jacob Vita was not the only Dalla Volta with this name who lived in Mantua in 1782, the year of purchase of this small book. Another Jew called “Jacob Vitta Volta” (so in the Italian documents) was born in Mantua, in 1751, son of Salvador and Anna Ricca, and there he died in 1795.

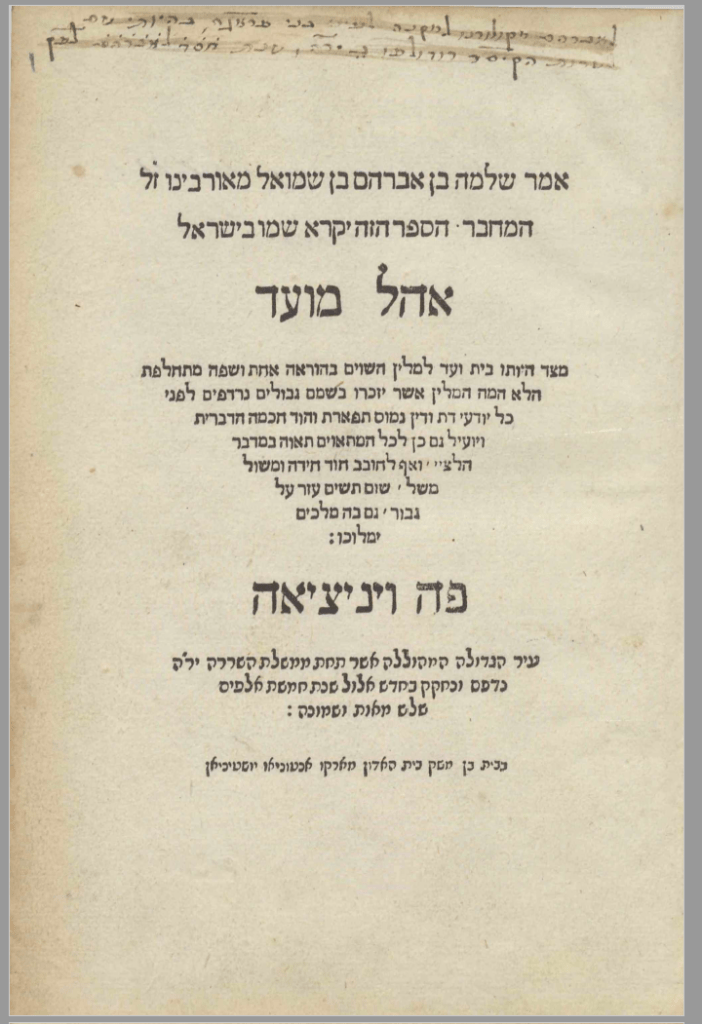

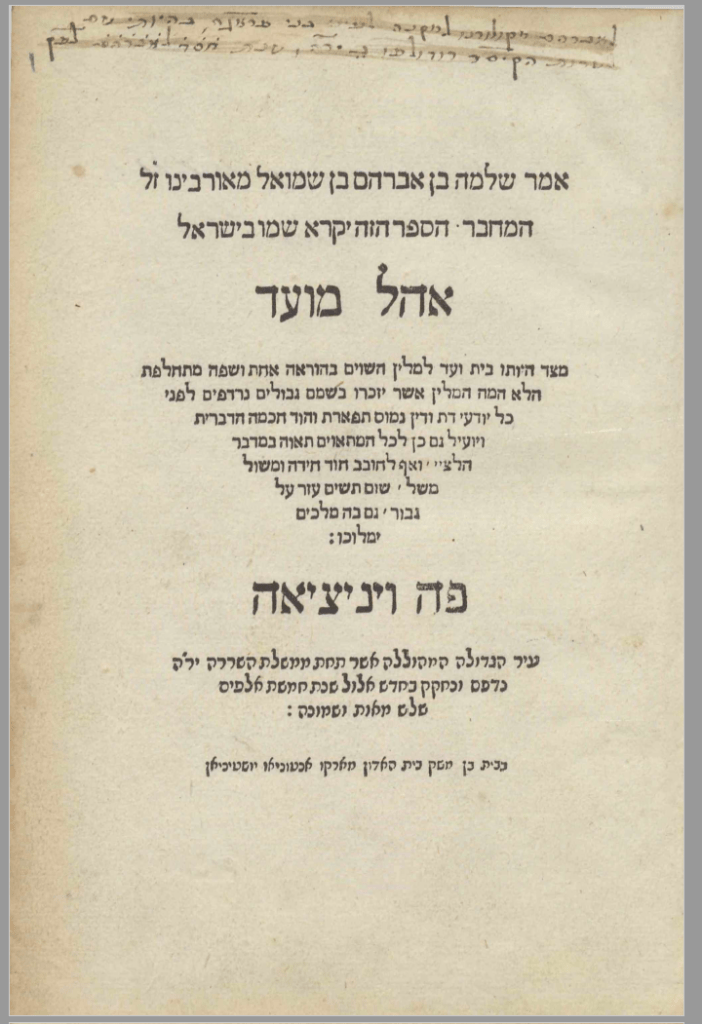

Figure 7. Šelomoh b. Avraham b. Šemuʼel, of Urbino, Ohel Mo‘ed, Venice 1548; title page. [Kaufmann B 33]

Hebrew cursive purchase note by Abramo Colorni written in Prague in 1590, slightly deleted.

In turn, a certain Ziporà gave birth on 1 January 1782 to Salomon Jacob Raffael, son of the late “Jacob Vita Volta”. To make matters worse, the dated signature “Iacob Vitta Volta 1764” appears on f. 1v of the incomplete third volume of a Torah at the Civic Library of Verona (shelf-number III.b.8), the Nevi’im Aḥaronim (“Latter Prophets”), Venice 1740. We cannot be sure whether he is the same man described here, since the Verona library also preserves a commented copy of the extremely popular ethical work Sefer Menorat ha-Ma’or by the early 14th century Spanish Talmudist and kabbalist Yiṣḥaq Aboab, published in Frankfurt am Main in 1743, signed in Italian by “Salvador Dalla Volta Dr. a Verona”, “David Dott. Dalla Volta” and “Prospero Dalla Volta” (shelf-number II.a.20) who were presumably members of a family not to be confused with the Dalla Voltas of Mantua. Perhaps “Iacob Vitta Volta” belonged to the Veronese branch of it.

[15]

Abramo Colorni (ca. 1544-1599)

One of the most remarkable books coming from Mantua is surely the Ohel Mo‘ed Venice 1548 (Kaufmann B 33; only edition), by Šelomoh b. Avraham b. Šemuʼel of Urbino (end of the 15th-century-beginning of the 16th-century), that was in the possession of the Mantuan Jew Abramo Colorni; ca. 1544-1599) [figure 7]. The contemporary binding of this book shows profiles of Latin classical authors (like Virgil, Cicero and Ovid) and virtuous inscriptions (i.e. “Iusticia” and “Spes”) that almost seem unsuitable for a lexicon on Biblical synonyms. Colorni was immersed in the culture of the world around him, and so it is possible that this is his original binding [figure 8].

Figure 8: Front plate of the German-type Renaissance leather binding.

As a young man, Abramo received a courtier-like education, and he worked for the Gonzagas as an alchemist, an inventor, a military architect and a creator of amazing fireworks. Colorni became famous outside Mantua as an engineer and mechanic, a mathematician, an archaeologist and a builder of clocks, and even as a conjurer and magician. Beginning in 1578 he started serving in the House of Este in Ferrara, and in April 1588, he left Ferrara for Prague. It was in Prague, in the service of emperor Rudolph II (1552-1612), in 1590, where he bought this copy of Ohel Mo‘ed. Rudolph II had established a court of alchemists, astrologers, and artists of various inclinations, and Colorni’s 1593 publication of Scotographia overo, scienza di scrivere oscuro, facilissima, et sicurissima, per qual si voglia lingua, dedicated to the emperor (see Kaufmann D 84, owned by Mortara), showed his connections to the court. Colorni would return to Mantua not before 1599.[16]

Figure 9: Yiṣḥaq Aboab, Sefer Menorat ha-Ma’or, Mantua 1563; f. 3v. [Kaufmann B 498]

Drawing cut off at the margin by the Mantuan scribe Malḵi’el b. Avraham Aškenazi of a menorah with captions that refer to the nerot (“branches”) namely the seven sections in which this book is divided.

A copy (Kaufmann B 498) of Menorat ha-ma’or by Y. Aboab, Mantua 1563, includes the unpublished Šemen la-Ma’or, a commentary to Menorat ha-Ma’or by Malḵi’el b. Avraham Aškenazi (Malchiel Tedeschi) [figure 9] The one in Kaufmann B 498 is the only existing copy. Malḵi’el was active in the Jewish community of Mantua during the years 1611-1630, including as community scribe from 1624 until 1630. He authored a Hebrew commentary on the biblical description of the ancient Israelite Tabernacle divided in two volumes: the first is on the building of the Tabernacle in the desert, the second is on the Temple in Jerusalem and its holy vessels. Two of its four known copies are in Budapest (Kaufmann A 554 and A 555), autographs.[17] The copy of Menorat ha-ma’or with Ashkenazi’s glosses was purchased by Kaufman in 1882 from rabbi Rafael Natan Rabinowitz (1835-1888), a Lithuanian antiquarian bookseller and an outstanding Talmudic scholar living in Munich. Rabinowitz sold several printed volumes and manuscript to Kaufmann in the 1880s.[18]

Aškenazi also owned three Kaufmann books that are currently missing, all from Mortara’s library:

1) Sefer yoreh ḥaṭa’im ba-dereḵ we-niqra Sefer ha-Kaparot le-ḵol ha-‘over ‘averah, Venice 1589 (Kaufmann B 324)

2) the Jewish catechism Leqaḥ ṭov by the Italian philosopher rabbi Avraham b. Ḥananyah Yagel (1553-1623), with a note by Samuel Vita Dalla Volta (Kaufmann B 325)

3) the Hebrew edition of the travels of Binyamin mi-Ṭudelah (1130-1173), Freiburg-im-Breisgau 1583 (Kaufmann B 326), with another note by S.V. Dalla Volta.

It is not always easy to identify who signed a volume even if one can read the full name because of the recurrence of the same names in families bearing the same surname, as was shown with respect to J.V. Dalla Volta; nor is it less complicated to place an owner in time when his signature is undated and no location is specified. This is the case with Mošeh Yosef Ariani, who bought the Be’urim by the Ashkenazi rabbi Yiśra’el b. Petaḥyah Isserlein (1390-1460), Venice 1545 (missing Kaufmann B 253, formerly Mortara). Ariani was a Jewish surname in the Mantuan area, and Mošeh Yosef Ariani’s Hebrew note can be attributed to the late seventeenth or the early eighteenth century, but in that period, there was more than one M.Y. Ariani in Mantua. In 1691 a Mošeh Yosef, son of the late Zekaryah Ariani copied some Kabbalah works (Oxford, Bodleian Libraries, ms. Mich. 143). This M.Y. Ariani also owned a kabbalistic manuscript by Ḥayyim b. Yosef Viṭal (1542 or 1543-1620) copied around the middle of the 17th century (formerly in Jerusalem, ms. K 94 of the collection of prof. Meir Benayahu, 1924-2009). In the registers of the Jewish Community of Mantua one can read the names of two more persons called Moisè Iseppe Ariani (so was the name written in Italian documents) who lived during the same century. One of them (Mošeh Yosef son of Zekaryah?), in 1710 and again in 1716 was chosen as a sort of inspector of the local Jewish school and a manager of its library. The second one – son of Felice Ariani (d. 1775), Massaro alla Polizia and later Massaro alla Guardia notturna (a man delegate to control that no one entered or left the ghetto at night) in the years 1740-1771, and of Bona Finzi (1720-1765) – was Massaro alla Guardia Notturna since December 1775 till December 1783; he was appointed on 28 December 1786 Massaro alle Prestanze (“Deputy to the Loans”). On 5 January 1794, Moisè Iseppe Ariani was one of the three new memonim (“appointees”) of the Jewish school of Mantua, the library catalogues of which they also received. He died on 3 September 1808 65 or 66 old, husband of Bona Ventura, daughter of Isach Rietti and Gentille Monseles, who died at 77 on 5 June 1818. Each of these men called Moisè Iseppe Ariani may have owned Kaufmann B 253.[19]

In another example, a 17th-century Binyamin Ḥayyim Ṣoref who signed himself in Hebrew at the top of the title page of Me-Harere Nemerim, Venice 1599 – a compendium of methodological essays on Talmud treatises

Figure 10: Šemu’el b. Avraham Aboab, Sefer ha-ziḵronot, Prague 1631-1651; inside back cover. [Kaufmann B 235]

Italian list of payments for goods, partially cropped at the top, probably drawn up on 11 May 1713, including prices and accounts in which Lazaro Colorni, member of some relevance in the Jewish community of Mantua, was mentioned. In the left margin a different hand wrote a partially cut off Italian rigmarole as an ownership.

(Kaufmann B 446; only edition) by the Italian scholar Avraham b. Šelomoh ‘Aqrah (ca. 1520- ca. 1600). Among Italian Jewry, the Hebrew surname Ṣoref became Orefice, chiefly in Mantua (registered there even as Oreffici) and Venice. Hence, he could be Benjamin Vita Orefice, but nobody with that identity has been found in any source.

[20] Likewise, it can only be supposed that Šelomoh Ḥayyim Ṣiviṭah, owner of

‘Et ha–

zamir, Venice 1707 (Kaufmann B 967; first edition, ex Mortara) – a collection of kabbalistic poems by Binyamin Kohen Viṭale (1651-1730) of Alessandria, in Piedmont – was the same Salomon Vita Civita who died in Mantua on 21 July 1743, where he was a significant member of the Mantuan Jewish community since 1718 till his death.

[21]

I’ll conclude this section on Mantuan inscription with some words on the copy of the treatise on ethical conduct Sefer ha-Ziḵronot, Prague, 1631-1651 (Kaufmann B 235; first edition) by the Venetian rabbi Šemu’el b. Avraham Aboab (1610-1694). Its transfers of property exemplify what has been written so far, with ownership by S. Sacerdote Modon, L.S. Dalla Volta, S.V. Dalla Volta and M. Mortara to D. Kaufmann. On its title page one can see the Italian signature “Sanson Sacerd[ot]e Modone” and in cursive Hebrew when he precisely purchased this book, namely on 21 November 1702, and the Hebrew numerals ב’ נ”ו, presumably corresponding to the shelf-marks of the library of Samuel Vita Dalla Volta. At the bottom of the verso of the title page S.V. Dalla Volta wrote in cursive Hebrew on 31 October 1830 that the author of this book was Šemu’el Aboab, following what Ḥayyim Yosef Dawid Azulai (1724-1806) had affirmed, since the name of Š. Aboab is not present on the title page. Furthermore, Dalla Volta marginally glossed and entered corrections in cursive Hebrew on some pages and the usual sticker of Mortara seems to appear on the spine. In addition, inside its covers, payments for goods (clothes, shirts, shoes, pants, and jewels) were listed in Italian, including prices and accounts, and written in the 1710s by several hands (perhaps including Kohen Modon), in which members of some relevance in the Jewish community of Mantua are named. This is an example of the usage of a volume for reasons other than its content. Finally, in the left margin a different hand wrote a partially cut off Italian ownership in the form of a rigmarole: “Mant[ova] // [Questo libro è di carta / Questa car]ta è di stracio. / [Questo stracio è di lino. Questo lino] è di terra. Qu[esta terra è di Dio. Questo lib]ro è il mio; / Mantova”, namely “This book is made of paper / This paper is made of rags. / This rag is made of linen. This linen is from the land. This land belongs to God. This book is mine.” [figure 10]. It was a way of claiming the property of a book mainly practiced in the 18th and 19th centuries (but still in the 20th century) by children and adults, in Italy and elsewhere. They wrote these words or words of similar meaning in their books so that they were not stolen or that they might be returned to them if lost.[22]

[1] See Ḥoḵmatḵem we-binatḵem le-‘einei ha-‘amim = Porto astronomico, Padua 1636 (Kaufmann B 288; first edition) by the Italian mathematician rabbi Emanuel Porto (Menaḥem Ṣiyyon Kohen Rapa Porṭo; d. ca. 1660), in which Mortara referred to Bibliotheca Judaica, Leipzig, 1863, III, p. 116, compiled by the German Hebraist Julius Fürst (1805-1873), where he listed works of E. Porto. Mortara also underlined that Porto in the dedication to Porto astronomico at p. 5 declared that this was his first Italian work. We can deduce that Mortara’s ex libris was printed by the Christian lithographer Lorenzo Podestà (b. 1815) since his name it is visible on some Mortara stickers (on L. Podestà, see Giancarlo Ciaramelli, Cesare Guerra, Tipografi, editori e librai mantovani dell’Ottocento, Milano, FrancoAngeli, 2005, pp. 23, 158, 164, 185-190, 192, 198)

[2] István Ormos, David Kaufmann and his collection, pp. 131, 138, in David Kaufmann Memorial Volume. Papers presented at the David Kaufmann Memorial Conference November 29, 1999, Budapest Oriental Collection Library of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences; Edited by Éva Apor, Budapest, MTAK, 2002; Asher Salah, La biblioteca di Marco Mortara, pp. 150, 152, 155, 157, 159-161, in Nuovi studi in onore di Marco Mortara nel secondo centenario della nascita; a cura di Mauro Perani e Ermanno Finzi, Firenze, Giuntina, 2016.

[3] A. Salah, L’epistolario di Marco Mortara 1815-1894). Un rabbino italiano tra riforma e ortodossia, Firenze, Giuntina, 2012, pp. 127-128.

[4] Bruno Di Porto, Marco Mordekai Mortara Doreš Tov, “Materia Giudaica” XV-XVI, 2010-2011, pp. 141, 149 (note 47); A. Salah, L’epistolario di Marco Mortara, p. 11.

[5] This is how the Mantuan rabbi Giuseppe Jarè (1840-1915) defined him in a letter published on 19 August 1879 in the Italian journal “L’Educatore Israelita”, XVIII, 1880, p. 280. On the contrary S.D. Luzzatto, who knew him personally, had a different opinion of him. In a Hebrew letter of 1831 Luzzatto wrote that he had met him in Padua and that he had not seemed not very smart to him, nonetheless a good thing was that Dalla Volta was always looking for and scrolling through books, cf. A. Salah, La biblioteca di Marco Mortara, p. 159.

[6] Mario Vaini, Città e campagne tra guerre e rivoluzioni (1797-1866), in Il paesaggio mantovano nelle tracce materiali, nelle lettere e nelle arti. IV. Il paesaggio mantovano dall’età delle riforme all’Unità (1700-1866). Atti del Convegno di studi, Mantova, 19-20 maggio 2005; a cura di Eugenio Camerlenghi, Viviana Rebonato, Sara Tammaccaro, Firenze, Olschki, 2010, p. 236

[7] Paolo Bernardini, La sfida dell’uguaglianza. Gli ebrei a Mantova nell’età della rivoluzione francese, Roma, Bulzoni, 1996, p. 87.

[8] Budapest, Library of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Kaufmann ms. A 481, pp. 140, 214, 219.

[9] Marina Romani, Gli ebrei nel contesto socio-economico mantovano del XIX secolo, “Materia Giudaica”, XV-XVI, 2012, p. 212.

[10] A. Salah, L’epistolario di Marco Mortara, pp. 67-76, 219-224.

[11] Mauro Perani, Per uno studio dell’opera e del pensiero di Marco Mortara: recenti scoperte di manoscritti ignoti, la sua bibliografia e piste di ricerca, con un’appendice di documenti inediti, “Materia Giudaica”, XV-XVI, 2010-2011, p. 34. The Zikronot is preserved in Carbonara Po (Mantua) in the collection of Gianbeppe Fornasa.

[12] A. Salah, Steinschneider and Italy, in Studies on Steinschneider: Moritz Steinschneider and the Emergence of the Science of Judaism in Nineteenth-Century Germany; edited by Reimund Leicht and Gad Freudenthal, Leiden; Boston, Brill, 2012, p. 428; A. Salah, L’epistolario di Marco Mortara, p. 126; A. Salah, La biblioteca di Marco Mortara, pp. 152-153, 155.

[13] Solomon Marcus Schiller-Szinessy, Catalogue of the Hebrew Manuscripts Preserved in the University Library, Cambridge, Volume 1, Cambridge, Cambridge University library, 1876, pp. 38-39, 43-44, 101-115, 221-226, 241-244, nos. 27, 30-31, 43, 69, 72, and Volume II, 1878, pp. 72-76, no. 93.

[14] Šemu’el Ḥay mi-Lavolṭah, Toledot ha-ḥakam Šimšon Kohen Modon z.ṣ.l. iš Manṭuah (“Story of the late wise Šimšon Kohen Modon, man of Mantua”), “Kerem Ḥemed”, II, 1836, p. 114 [in Hebrew].

[15] Edizioni ebraiche dei secoli XVI-XIX, pp. 3, 8-9, nos. 2, 15, in La biblioteca della comunità ebraica di Verona. Il fondo ebraico; a cura di Daniela Bramati … [et al.]; sotto la direzione scientifica di Crescenzo Piattelli, Giuliano Tamani, Verona, Biblioteca civica, 1999; Archivio Digitale della Comunità Ebraica di Mantova. Registro 2. Morti dal 1769 al 1815, <http://digiebraico.bibliotecateresiana.it/sfoglia.php?tipo=registro&op=esplora_ric&gruppo= REG001024;REG025042&sottogruppo=REG002&offset=>, Registro 4. Nati dal 1770 al 1847, <http:// digiebraico.bibliotecateresiana.it/sfoglia.php?tipo=registro&op=esplora_ric&gruppo=REG001024;REG025042& sottogruppo=REG004&offset=0>, Registro 9. Nati dal 1750 al 1775, <http://digiebraico. bibliotecateresiana.it/sfoglia.php?tipo=registro&op=esplora_ric&gruppo=REG001024;REG025042&sottogruppo= REG009&offset=0>, Registro 17. Morti dal 1797 al 1847, <http://digiebraico.bibliotecateresiana.it/sfoglia.php?tipo=registro&op=esplora_ric&gruppo=REG001024;REG025042&sottogruppo=REG017&offset=0>, Registro 34. Registro comunità A-L, letter D, plates nos. 4 and 7, <http://digiebraico.bibliotecateresiana.it/sfoglia.php?tipo =registro&op=esplora_ric&gruppo=REG001024;REG025042&sottogruppo=REG034&offset=0>, Registro 42. Matrimoni 1773 – 1815 / Popolazione 1774 – 1815, <http://digiebraico.bibliotecateresiana.it/sfoglia.php?tipo= registro&op=esplora_ric&gruppo=REG001024;REG025042&sottogruppo=REG042&offset=0>; Budapest, Library and Information Centre of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, ms. Kaufmann A 481, pp. 133-135, 141, 143-144, 215.

[16] Biographical details are available in Daniel Jütte, Das Zeitalter des Geheimnisses. Juden, Christen und die Ökonomie des Geheimen (1400–1800), Göttingen, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2011, pp. 171-321.

[17] Shlomo Simonsohn, History of the Jews in the Duchy of Mantua, Jerusalem, Kiryath Sepher, 1977, pp. 347 (note 103), 477-478 (note 513); Archivio Digitale della Comunità Ebraica di Mantova, Sezione Antica. Etica. Volume III. Libro VI, pp. 384-385, <http://digiebraico.bibliotecateresiana.it/sfoglia.php?tipo=repertorio&op=esplora_ric&gruppo= REP001010&sottogruppo=REP003&offset=0>.

[18] Adolf Brüll, “Rabinowitz, Raphael Nathan”, pp. 186-187, in Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie, LIII, Leipzig, Duncker & Humblot, 1907; I. Ormos, pp. 141, 157.

[19] Archivio Digitale Della Comunità Ebraica Di Mantova. Sezione Antica. Etica; Volume III, Libro VI, pp. 8-9, Sezione Antica. Filza 238, cartella 5, <http://digiebraico.bibliotecateresiana.it/filze_gruppo.php?op=esplora_ric&cata=ebraici& gruppo=FIL238>, Registro 9. Nati dal 1750 al 1775, Registro 16. Morti dal 1816 al 1838, <http://digiebraico. bibliotecateresiana.it/sfoglia.php?tipo=registro&op=esplora_ric&gruppo=REG001024;REG025042&sottogruppo= REG016&offset=0>, Registro 17. Morti dal 1797 al 1847, Registro 18. Morti dal 1750 al 1769, <http://digiebraico.bibliotecateresiana.it/sfoglia.php?tipo=registro&op=esplora_ric&gruppo=REG001024;REG025042 &sottogruppo=REG018&offset=0>.

[20] Vittore Colorni, La corrispondenza fra nomi ebraici e nomi locali nella prassi dell’ebraismo italiano, p. 695, in his Judaica minora. Saggi sulla storia dell’ebraismo italiano dall’antichità all’età moderna, Milano, Giuffrè, 1983.

[21] Archivio Digitale della Comunità Ebraica di Mantova, Sezione Antica. Etica; Volume III, Libro VI, p. 82.

[22] Francesco Novati, Scrittori e possessori di codici, “Il Bibliofilo”, III, 1882, 3, pp. 38-41. A Jewish use of this Italian tiritera is readable for instance on f. 291v of Cod. Parm. 1872 at the Palatina Library of Parma.

Recent Comments