Despite our conclusion that little empirical research exists linking the relationship between sustainability and happiness in Scandinavian countries including Norway, Sweden and Denmark, environmental policy experts, educators, and social scientists are dedicated to studying and furthering this issue.

Catherine O’Brien a Professor of Education at Cape Breton University in Sydney, Canada noticed that up until recently, “research on happiness was not taking sustainability into account.” Sustainability was being treated as an “isolated” issue.

It struck Dr. O’Brien that, “a lot of happiness research reinforced what we were saying about sustainability,” but that a connection between the two was not being made. She notes that in the past few years this has been shifting as sustainability is beginning to be included in conversations of positive psychology.

In order to further challenge these conversations, Dr. O’Brien used her experience in environmental education to pioneer a concept of sustainable happiness. Dr. O’Brien has developed the first post-secondary course in sustainable happiness and has also recently created a certificate in sustainable happiness for professionals. These are only a few of her many achievements in this field.

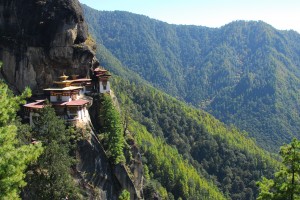

To see where sustainable happiness is being taken very seriously, look no further than Bhutan, where the government presumes a relationship between happiness and sustainability. In fact because of her efforts in sustainable happiness, Dr. O’Brien has been invited to Bhutan in 2015.

Bhutan is unique in its unmatched dedication to the well being of its people and the sustainability of its resources. There was no better location for UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon to introduce, the International Day of Happiness, a new holiday recognized by the international community, than in Bhutan in 2012. The International Day of Happiness is celebrated on March 20 in order to recognize the importance of happiness for citizens of all countries.

First and foremost, Bhutan rejects traditional international standards of economic prosperity, the Gross Domestic Product (GDP). The internationally accepted standard is to measure a country’s well being through its GDP.

What exactly does GDP capture? From a very simple perspective, GDP measures the total monetary value of all finished goods and services produced within a country in a specific time period – generally one calendar year.

To understand why Bhutan rejects GDP as a measure of well being, we must trace this decision back to Bhutan’s distinct history and culture. The country is just recently emerging from its own self-imposed isolation, which lasted up until the early 1960s. As a result, Bhutan has vast amounts of untapped environmental resources and an unleashed economic capacity. The two are intricately linked. By not engaging in manufacturing and other modern sectors until recently, Bhutan has been able to preserve its natural resources unlike its rapidly developing neighbors, China and India. The country in fact only adopted a democratic structure as recently as 2008.

So with its newfound opportunities, why would Bhutan reject traditional notions of material well being in favor of its own measure of personal happiness?

This mindset is deeply rooted in Bhutan’s history and rich Buddhist culture. The South Asian country is located in the Eastern Himalayan region considered by some to be a “sensitive geopolitical position,” due to its neighbors to the North, China and to its South, India. The population pales in comparison to its neighbors, the 2005 census estimated the population to be roughly 634,892 inhabitants.

As a result of its newfound modernization, the economy is still centered on traditional agricultural trades such as farming, animal husbandry, and forestry, which account for roughly 40 percent of its GDP. (Yes, while Bhutan may not recognize GDP – it can still be measured). The country’s more modern sectors, which include manufacturing, are currently at 30 percent.

Driving along the windy roads in Bhutan are hand-painted signs asking drivers not to slow down bur rather suggesting ideas such as, “Let nature be your guide.”

This declaration resonates throughout the country’s Constitution. It was written into law that in order to conserve Bhutan’s natural resources, “a minimum of 60% of Bhutan’s total land shall be maintained under forest cover for all time.”

About 10 years prior to the recently adopted Constitution, the GNH was introduced. Then Prime

Minister Jigmi Y. Thinley presented the concept at a Keynote address for the UN Development Programme Regional Millenium Meeting for Asia and the Pacific in 1998.

In describing the concept, Thinley stated to the UN that GNH is “based on the belief that the aspiration, the ultimate goal of every human individual, is happiness, so then it must be the responsibility of the state, or the government, to create those conditions that will enable citizens to pursue this value, this goal.”

Thinley explains the four pillars of GNH as being sustainable and equitable socioeconomic development, environmental conservation, promotion of culture, and good governance. These pillars are measured among nine dimensions to help establish a quantifiable indicator of happiness. These indicators are: health, education, living standards, time use, environmental quality, culture, community vitality, governance, and psychological well-being.

Though it has rejected measures of material well being, Bhutan cannot escape the fact that it is still incredibly poor.

So we must ask, has Bhutan seen any measurable success?

As a recent approach, research continues to emerge. In 2008, the Centre for Bhutan Studies looked at average happiness levels for 7 South Asian countries, finding that while Bhutan ranked at the top of the list, differences were minimal. Other accounts find that Bhutan’s life expectancy has almost doubled.

All in all, Bhutan’s approach to happiness and sustainability is unique and admirable. We can only wonder what the rest of the international community would look like if they too adhered to Gross National Happiness.