In the 1950s United States Secretary of Agriculture Ezra Taft Benson told farmers to “get big or get out.” Today, if one looks at the industrial livestock sector it seems that Benson’s vision of large-scale agriculture has come to fruition. The contemporary meat industry in the United States is a powerful force in both business and politics. The rise of the sector can be explained by a number of developments in production and technology dating back to the first European settlements in North America.

In the 17th century, meat was regarded as a luxury item for the elites of European society, however in the newly established North American colonies it was commonplace. Settlers filled the wide expanses of viridescent meadows with domesticated livestock and worked to establish civilization amidst what they considered savage lands. This civilizing mission stemmed in part from Christian doctrine, which placed humans as masters over all living creatures. Livestock became essential to New World settlers looking to replicate and improve upon the civility of Europe.

Raising livestock became an “emblem of civilized life” as well as a significant source of wealth and nutrition. In the New World livestock ownership provided financial security without much labor. While tobacco and cotton required the labor of indentured servants and slaves, tending livestock necessitated several farmers, fences, and pastures. According to historian Maureen Ogle in In Meat We Trust, “one cow and a calf carried as much monetary value as six or seven hundred pounds of tobacco, a third of a year’s crop for one man” in the late 1600s. The widespread availability of land further facilitated the proliferation of domesticated animals and contributed to the development of meat-centric diets. By the 1650s, livestock outnumbered English colonists and meat became a dietary staple.

Initially, the settlers of the New World practiced traditional forms of animal husbandry, in which farmers strived to balance agricultural production with the conservation of natural resources. For instance, husbandmen worked mindfully and directly with their land and animals, carefully tending to the needs of both. Farmers had daily physical interaction with their livestock and gained intimate knowledge of how to maintain animal health and wellbeing. Raising livestock involved protecting the animals from predators, overseeing successful births, and treating all illnesses. Livestock assisted farmers in that they fertilized fields for crop production. Domesticated animals almost seemed like members of the family, as they were named and so readily cared for. Further, husbandry embodied a holistic outlook on the environment, in which livestock, farmers, and nature existed in a mutually beneficial relationship.

In the early 1800s, hoards of people concentrated in major cities along the northeast coast, while farmers migrated west onto fertile soils. Yet, with larger consumer bases located long distances away from the farms, meat producers had to shift their attention from the subsistence of the local community to providing for the cities. A host of technological advances helped meat producers overcome the supply and demand challenges presented by urbanization.

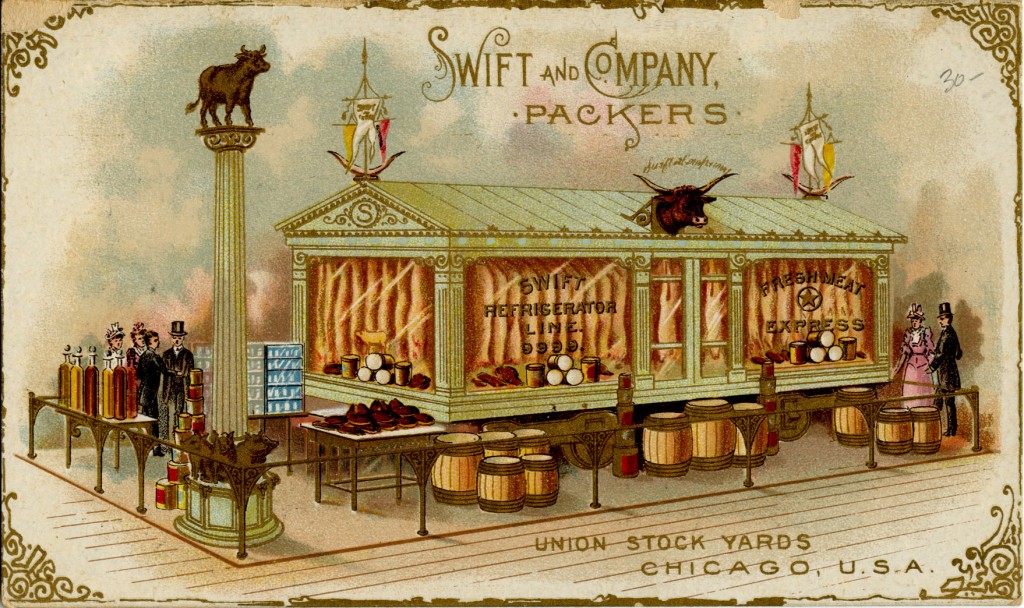

The construction of the United States railroad system in the early 1830s and 1840s allowed farmers to ship livestock and raw goods to urban markets and slaughterhouses. During transport, however, livestock were often injured and arrived in cities in poor health, thus rendering shipments less profitable. Further, transporting living livestock was expensive. In response to these difficulties, Gustavus Swift introduced the refrigerated rail car in the late 1800s. His innovation allowed farmers to ship cheap, fresh beef rather than live animals, maximizing the amount of edible product one could ship and the profit to be made. By 1882, Swift’s refrigerated rail cars were transporting beef year round to New England, New York, and Washington DC.

At the start of the twentieth century, farming abandoned husbandry and embraced profit-centric, industrial form of agriculture. In the 1920s, industrial animal farms received a significant boost with the introduction of antibiotics and vitamins A and D to animal feed. These additions accelerated processes of production, while government subsidies further supported shifts toward large-scale agriculture. The traditional tools of hoe and plow were replaced by machinery. Animals no longer grazed in pastures; conversely livestock were confined in unsanitary and enclosed living quarters. Livestock manure accumulation, in addition to a host of other factors, led to higher methane emissions. The move away from husbandry broke the intimate relationship between humans and nature.

The rise of the industrial livestock sector is marked by efforts to feed a growing and urbanizing nation, in addition to the heedless pursuit of profit. The state of the industrial livestock sector is a departure from the era of husbandry seen during colonial times. A primary difference between contemporary meat production and husbandry is the externalization of environmental factors. While husbandmen considered the wellbeing of the environment as a crucial part of agriculture, corporate meat producers disregard greenhouse gas emissions and pollution created by the production of livestock.

Nevertheless, meat-centric colonial diets set the foundation for the societal demand for meat today. In order to internalize the environmental impacts of the meat industry, the federal government might consider subsidies for local, organic farms in addition to heavy regulation of the industrial livestock sector. Additionally, a change in consciousness is needed on behalf of the population to reduce the amount of industrial meat consumption. To change attitudes, not-for-profits and the government could also look to the developing fields of behavioral science. Looking forward, this blog will give a more comprehensive overview of the industrial livestock sector in relation to climate change, and provide potential solutions.