The narrative of hardened criminals finding God in prison has become so clichéd that it is now frequently mocked in popular culture. Take the hit television show, Orange is the New Black, a “dramedy” chronicling life in a women’s prison in upstate New York. One of the characters on the show, Tiffany “Penssatucky” Dogget, is sent to prison for shooting a nurse at an abortion clinic after the nurse makes a snide comment about Penssatucky’s many abortions. After the murder, Penssatucky becomes a hero of the Christian pro-life movement. Pro-life activists pay her legal fees and spin a new narrative about Penssatucky’s life, wherein she is not a criminal meth addict but rather a crusader for the lives of unborn fetuses. Penssatucky adopts her new faith with zeal, which Orange is the New Black plays for laughs. Take this clip, for example (link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=APtdhih9pwU).[1] Penssatucky is portrayed as a stupid, crude hillbilly with comically ridiculous religious views. Accordingly, Penssatucky’s gradual abandonment of her evangelical faith over the course of the series represents her character development and growth.

Yet religious conversion in prison is a deeply felt experience for many prisoners. This is true for adherents of many religions – Malcolm X and the Nation of Islam stand out as a particularly strong example of the potency of religious experience in prison. In this blog post, however, I will focus on Christianity, using the Gospel According to Matthew to help understand the appeal of Christianity for those who are incarcerated. I will intersperse my textual analysis with some especially powerful images from Serge J-F. Levy’s series of photographs documenting religious practice in maximum-security prisons.

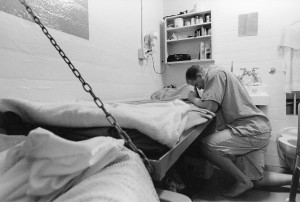

A prisoner praying at Minnesota Correction Facility[2]

In a 2006 study of prisoners who converted to Christianity, criminologists Shadd Maruna, Louise Wilson, and Kathryn Curran argue many prisoners use conversion to overcome the stigma of their imprisonment. Christianity thus serves as a “tool for shame management.”[3] Rather than identify as prisoners or criminals, converts come to see themselves first and foremost as Christians.[4] Furthermore, Christianity offers prisoners a “framework for forgiveness.”[5] For those who have committed serious crimes, the concept of equality is particularly appealing, suggesting that “all people need forgiveness and we are all children of God.”[6] Indeed, in the Gospel According to Matthew, Jesus warns, “For if you forgive men their trespasses, your heavenly Father also will forgive you; but if you do not forgiven men their trespasses, neither will your father forgive your trespasses” (Matthew, 7:14-15).

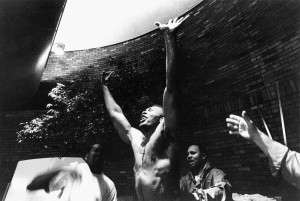

Prisoners baptize one another in a laundry cart at Minnesota Correction Facility[7]

Significantly, sinners play a central role in the Gospel According to Matthew. This is not to say that Matthew is lax about religious rules; in fact, the religious dictates in the gospel are in many cares far more stringent than those in the Hebrew Bible. For example, not only may one not have extramarital sex, but “one who looks at a woman lustfully has already committed adultery with her in his heart” (Matthew, 5:27). Nevertheless, Jesus displays great compassion for sinners. When Jesus’s disciples question his decision to eat dinner with “tax collectors and sinners,” Jesus tells them, “Those who are well have no need of a physician, but those who are sick. Go and learn what this means, ‘I desire mercy, and not sacrifice.’ For I came not to call the righteous, but the sinners” (Matthew, 9:11-13). Those who reform are true Christians. Indeed, Jesus tells the Jewish priests at the temple in Jerusalem, “John came to you in the way of righteousness, and you did not believe him, but the tax collectors and the harlots believed him; and even when you saw it, you did not afterward repent and believe him” (Matthew, 21:32). Throughout Matthew, Jesus displays genuine faith in the ability of sinners to reform.

A prayer circle at Louisiana State Penitentiary[8]

I thus argue that religious experience in prison is more genuine and nuanced than popular shows like Orange is the New Black suggest. Indeed, it is unsurprising that Christianity should hold genuine appeal for those who are incarcerated. Conversion to Christianity offers prisoners a path to forgiveness and validates their human worth, unlike the harsh American prison system. Rather than carrying the stigma of criminality, through conversion, prisoners are able to reinvent themselves as Christians worthy of God and entrance into the kingdom of heaven.

Bibliography

Maruna, Shadd, Louise Wilson, and Kathryn Curran. “Why God Is Often Found Behind Bars: Prison Conversions and the Crisis of Self-Narrative.” Research in Human Development 3 (2006): 161-184.

Netflix. “The Chickening.” Orange is the New Black video, 1:34. July 11, 2013. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=APtdhih9pwU.

Teicher, Jordan G. “Finding God in Maximum Security Prison.” Slate, January 3, 2014. Accessed December 5, 2015. http://www.slate.com/blogs/behold/2014/01/03/serge_j_f_levy_photographs_religious_worship_in_maximum_security_prisons.html.

“The Gospel According to Matthew” in May, Herbert G., and Bruce M. Metzger, ed. The New Oxford Annotated Bible with the Apocypha. New York: Oxford University Press, 1977.

Note: I tried to speak with members of the Riverside Church Christian Prison Ministry for this blog post. In doing so, I hoped to understand the religious motivations behind members’ work with prisoners and desire to institute prison reform. However, I never received responses to my phone calls to the organization, and when I tried to attend a meeting listed on their website, no one ever showed up.

[1] Netflix, “The Chickening,” Orange is the New Black video, 1:34, July 11, 2013, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=APtdhih9pwU.

[2] Jordan G. Teicher, “Finding God in Maximum Security Prison,” Slate, January 3, 2014, accessed December 5, 2015, http://www.slate.com/blogs/behold/2014/01/03/serge_j_f_levy_photographs_religious_worship_in_maximum_security_prisons.html.

[3] Shadd Maruna, Louise Wilson, and Kathryn Curran, “Why God Is Often Found Behind Bars: Prison Conversions and the Crisis of Self-Narrative,” Research in Human Development 3 (2006), 164.

[4] Maruna et al., “Why God Is Often Found Behind Bars,” 174.

[5] Ibid., 175.

[6] Ibid., 178.

[7] Teicher, “Finding God in Maximum Security Prison.”

[8] Teicher, “Finding God in Maximum Security Prison.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.