In 1515, Bartolomé de Las Casas gave up his slaves and encomienda in the Spanish West Indies. Slave labor could be highly lucrative for individual slaveholders and was becoming increasingly important to the economy of the Spanish Empire. However, as a result of his interactions with the indigenous peoples of the West Indies, de Las Casas concluded that their enslavement by Europeans was unjust. In An Apologetic History of the West Indies, de Las Casas lamented the general trend in European writing on the indigenous peoples of the Americas – “that these peoples of the Indies, lacking human governance and ordered nations, did not have the power of reason to govern themselves.”[1] Instead, de Las Casas aimed “to demonstrate the truth, which is the opposite.”[2] Using a kind of proto-ethnography, de Las Casas described the highly developed economy, government, judicial system, and military of these indigenous peoples, humanizing his subjects through his writing and concluding that in many cases these indigenous peoples were more “civilized” than their European counterparts.

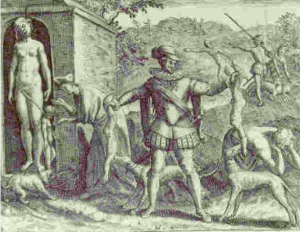

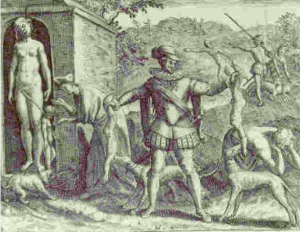

Theodore De Bry’s illustration for de Las Casas’s Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies highlights the violent “barbarism” that de Las Casas argued characterized much of European colonization.[3]

De Las Casas carefully deconstructed the categories of “barbarian” and “civilized,” illustrating both the complexity and the relativism of these terms. For example, while acknowledging that the indigenous peoples of the West Indies were barbarians in that they could not communicate effectively in Spanish, de Las Casas pointed out, “In this we are as barbarian to them as they to us.”[4] Significantly, in de Las Casas’s complex four-level classification scheme of barbarians, only the third type, “who by their strange, harsh and evil customs, or by their evil and perverse inclination, turn out cruel and ferocious and, unlike other men, are not governed by reason,”[5] may be enslaved. Following Aristotle, de Las Casas called these people “slaves by nature,” writing that “wise men can hunt or track them like animals in order to bring them under control and make use of them… and profit their wise regent from their physical strength, because nature has made them robust for any work and chores which they might be ordered to do.”[6] According to de Las Casas, the indigenous peoples of the West Indies were definitively not of this mold. Instead, “They have their kingdoms and kings, armies, well-ruled and orderly states, houses, treasuries, and homes; they live under laws, codes and ordinances; in administering justice they prejudice no one.”[7] Thus enslaving them for profit or committing violent acts against them would be both unjust and inhumane.

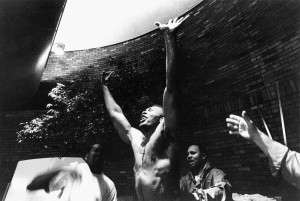

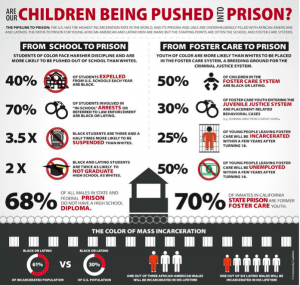

There are some striking parallels between Europeans’ enslavement of indigenous peoples in the Americas and the existence of private, for-profit prisons in the contemporary United States. These similarities did not go unnoticed by the members of Columbia Prison Divest, a group of activists here at Columbia who succeeded last June in pressuring the university to divest from private prison corporations after a series of well-organized protests, sin-ins, and teach-ins. At the beginning of this short documentary about the movement (link: https://www.facebook.com/theLFshow/videos/10153773781494721/?pnref=story), activist Asha Rosa explains, “Private prisons and the way that they’re using the incarceration of black and brown bodies as a way to make money, exploit people, and control political power is just a new iteration of a system that has been going on since this land was first colonized.”[8] Private prisons are thus not concerned with administering justice, but rather with making money. Reads a post on the group’s Twitter account, “Profit is one of the motivating forces behind how the state approaches ‘justice.’”[9] Just as de Las Casas concluded that even the economic benefits of slavery could not justify the enslavement of the indigenous peoples of the West Indies, Columbia Prison Divest argued effectively for “People over profit.”

Photo of a Columbia Prison Divest protestor carrying a sign with the slogan, “People over Profit”[10]

Unlike in de Las Casas’s era, today it is taboo to openly profit from racist subjugation. However, the Columbia Prison Divest activists worked to make explicit the continuity of racist oppression from slavery to private prisons and the ways that Columbia has profited from this oppression. Activist Dunni Oduyemi explains that the group put an “Abolish” banner on Columbia’s Thomas Jefferson statue to highlight that “this school is built on stolen land by slaves and Columbia has all these, like, statues memorializing that exact point in history.”[11] Likewise, Columbia Prison Divest drew attention to how Columbia supported the massive police raids in Harlem housing projects last summer, which targeted largely young men of color. In doing so, the university sought to gentrify the neighborhood and expand Columbia into West Harlem.

Photo of a Columbia Prison Divest protestor, whose sign reads “…because CU is profiting from a racist system”[12]

Much of the power of de Las Casas’s writing came from his ability to humanize the indigenous peoples he wrote about and expose the cruelty of European colonization. Likewise, throughout their campaign Columbia Prison Divest argued powerfully that prisons, not prisoners, are inhumane. Reads a message on their twitter feed, “Prisons are inhumane. Period. Innocence is irrelevant in a syst[em] of racism & punishment as opposed to accountability & care.”[13] By skillfully exposing the ways Columbia profits from systems of cruel and racist oppression, the activists of Columbia Prison Divest were able to succeed in forcing to Columbia to divest ten million dollars of its endowment from private prisons.

Bibliography

CU Prison Divest. Twitter post. April 23, 2015. 11:42 a.m. https://twitter.com/cuprisondivest/status/591311277504466945.

CU Prison Divest. Twitter post. April 24, 2015. 12:48 p.m. https://twitter.com/cuprisondivest/status/591690108400705536.

De Bry, Theodore. Image 9. “Theodore De Bry’s Illustrations for Bartolome de Las Casas’s Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies.” Accessed December 5, 2015. http://www.lehigh.edu/~ejg1/doc/lascasas/casas.htm.

De Las Casas, Bartolomé. Apologetic History of the Indies: Apologetic and Summary History Treating the Qualities, Disposition, Description, Skies and Soil of These Lands; and the Natural Conditions, Governance, Nations, Ways of Life and Customs of the Peoples of These Western and Southern Indies, Whose Sovereign Realm Belongs to the sMonarchs of Castile. In Columbia College, Introduction to Contemporary Civilizations in the West, 3rd ed. New York: Columbia University Press, 1960.

Divestment Victory at Columbia University. Directed by Laura Flanders. New York City: The Laura Flanders Show, 2015. https://www.facebook.com/theLFshow/videos/10153773781494721/?pnref=story.

Fox, Danielle. September 26, 2014. Photograph. Columbia Prison Divest Facebook Page. Accessed December 5, 2015. https://www.facebook.com/columbiaprisondivest/photos/pb.1376345619301146.-2207520000.1449613986./1475676042701436/?type=3&theater.

Fox, Danielle. September 26, 2014. Photograph. Columbia Prison Divest Facebook Page. Accessed December 5, 2015. 2015, https://www.facebook.com/columbiaprisondivest/photos/pb.1376345619301146.-2207520000.1449632259./1475677156034658/?type=3&theater.

Murphy, Henry. Photograph. Columbia Prison Divest Facebook Page, accessed December 5, 2015, https://www.facebook.com/columbiaprisondivest/photos/pb.1376345619301146.-2207520000.1449628076./1487411491527891/?type=3&theater.

[1] Bartolomé de Las Casas, Apologetic History of the Indies: Apologetic and Summary History Treating the Qualities, Disposition, Description, Skies and Soil of These Lands; and the Natural Conditions, Governance, Nations, Ways of Life and Customs of the Peoples of These Western and Southern Indies, Whose Sovereign Realm Belongs to the Monarchs of Castile, in Columbia College, Introduction to Contemporary Civilization in the West, 3rd ed. (New York: Columbia University Press, 1960), 1.

[2] De Las Casas, Apologetic History of the Indies, 1.

[3] Theodore De Bry, Image 9, “Theodore De Bry’s Illustrations for Bartolome de Las Casas’s Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies,” accessed December 5, 2015, http://www.lehigh.edu/~ejg1/doc/lascasas/casas.htm.

[4] De Las Casas, Apologetic History of the Indies, 8.

[5] De Las Casas, Apologetic History of the Indies, 5.

[6] De Las Casas, Apologetic History of the Indies, 5.

[7] De Las Casas, Apologetic History of the Indies, 7.

[8] Divestment Victory at Columbia University, directed by Laura Flanders (2015; New York: The Laura Flanders Show). It is also important to note that it is disproportionately black and Latino inmates who are incarcerated at private prisons.

[9] CU Prison Divest, Twitter post, April 23, 2015, 11:42 a.m., https://twitter.com/cuprisondivest/status/591311277504466945.

[10] Danielle Fox, September 26, 2014, photograph, Columbia Prison Divest Facebook Page, accessed December 5, 2015, https://www.facebook.com/columbiaprisondivest/photos/pb.1376345619301146.-2207520000.1449613986./1475676042701436/?type=3&theater.

[11] Divestment Victory at Columbia University.

[12] Henry Murphy, October 22, 2014, photograph, Columbia Prison Divest Facebook Page, accessed December 5, 2015, https://www.facebook.com/columbiaprisondivest/photos/pb.1376345619301146.-2207520000.1449628076./1487411491527891/?type=3&theater.

[13] CU Prison Divest, Twitter post, April 24, 2015, 12:48 p.m., https://twitter.com/cuprisondivest/status/591690108400705536.