Plato’s description of his ideal republic appears to stand in stark contrast to what are widely held to be core American values, including social mobility, freedom, and equality. Indeed, Plato imagines a republic rooted in hierarchy and inequality, where people are bred and educated to be members of certain classes and perform specific societal roles. According to Plato, “we aren’t all born alike, but each of us differs somewhat in nature from the others, one being suited to one task, another to another.”[1] Through selective breeding and differentiated education, Plato’s republic cultivates each person to perform his/her predetermined role as a member of a distinct class. Furthermore, using censorship and state lies, the rulers of Plato’s republic make rebellion and revolution impossible. Plato’s “Myth of Metals,” or “one noble falsehood,”[2] functions to make people amenable to the hierarchy of the republic. According to this myth, people are created with either gold, silver, iron, or bronze mixed into their souls, making them rulers, auxiliaries (soldiers), famers, or craftsmen respectively. Thus inequality is both naturalized and valorized. Although Plato’s republic may seem abhorrent to Americans raised on the ethos of the American Dream, it is not impossible to imagine the American Dream as its own kind of “noble falsehood.” While the American Dream leads Americans to believe that through hard work, anyone can achieve success, the reality is often quite different. Indeed, my examination of the school-to-prison pipeline will ask whether the way the American education system funnels certain children into prisons by talking about criminality rather than systemic racism or failing schools is really so alien to Plato’s ideal republic.

http://www.nytimes.com/video/us/100000004001301/police-officer-grabs-high-school-student.html?action=click&contentCollection=us&module=lede®ion=caption&pgtype=article[3]

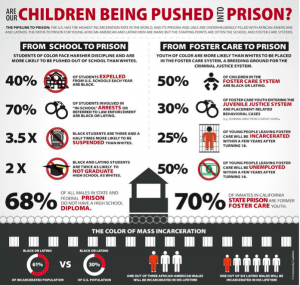

This October 26 video linked above from South Carolina’s Spring Valley High School shows a white police officer violently grab an African American student seated at her desk, throw her to the ground, drag her across the floor, and handcuff her. The video immediately went viral; indeed, an important difference between our contemporary world and Plato’s republic is that modern technology would render any attempt at total state censorship impossible. In addition to contributing to current conversations about racialized police violence, this video reignited national discussion of the school-to-prison pipeline. This term describes the phenomenon by which American children are funneled out of school and into the criminal justice system. The American Civil Liberties Union explains this happens because of the underfunding of public schools, the institution of draconian zero-tolerance policies, the elimination of due process for students, and reliance on law enforcement rather than teachers and school administrators to discipline students.[4] According to a 2013 New York Times article, these policies were prompted by an increase in juvenile crime in the 1980s and the Columbine High School shootings in the 1990s.[5] Significantly, however, the school-to-prison pipeline does not impact all American schoolchildren equally. The infographic below illustrates that it is disproportionately students of color – like the girl from the video – who drop out of school, experience expulsion, and find themselves entangled with the juvenile and criminal justice systems.

Indeed, while there is no evidence to suggest that students of color commit more crimes than their white counterparts, no fewer than seventy percent of students arrested in school are black or Latino/a. Not entirely unlike Plato’s education system that grooms people from birth to fulfill predetermined societal roles, it seems clear that America’s current education system sets certain children up to become a criminal underclass. However, by speaking of criminality rather than systemic racism or failing public schools, mainstream discourse about juvenile offenders disguises the operation of the school-to-prison pipeline, justifying inequality like Plato’s “Myth of Metals.”

What can be done to counteract the school-to-prison pipeline? Last October, the radio show This American Life produced an hour-long episode exploring how different schools discipline their students. While the entire episode is worth listening to (link here: http://www.thisamericanlife.org/radio-archives/episode/538/is-this-working), here I will discuss the third segment of the show. “The Talking Cure” chronicles life at Lyons Community School in Brooklyn, which serves mostly minority and low-income students. Here teachers and administrators practice restorative justice, talking through conflicts with their students. Recounting her semester spent reporting at Lyons, Joffe-Walt reflects that everything seemed to be going smoothly until a group of students and their teachers ventured outside Lyons for a fieldtrip. While on the subway, a large man bumped into one of the Lyons students, Nelson, who told the man, “Say excuse me.”[7] The man replied, “Fuck you,” to which Nelson answered, “Fuck you too.”[8] Other students jumped to Nelson’s defense and the conflict became physical, escalating until the man pulled out a police badge and identified himself as a plainclothes officer. Although the Lyons teachers tried to negotiate with the officer, he arrested Nelson and another boy. Each sixteen years old, the pair spent the night in jail. The incident forced Lyons to reconsider the utility of their program of restorative justice. Some administrators were angry. Dean Dan Espinoza (Espy) “imagined Nelson getting his prints taken, standing before a judge, seeing himself as a criminal. And Espy played out the alternative future he could now see for Nelson… seeing a path laid out for him, seeing him targeted by strangers who don’t see him for who he is. It made Espy furious.”[9] Meanwhile, teacher Cindy Black expresses her contrasting opinion: “We’ve let him [Nelson] get away with too much… We should have been more black and white… And so it’s our fault he’s done something now. He spent the night in jail. It’s because of us. It’s because of me.”[10] Recalling watching the incident unfold, a third teacher, Jesse, explains, “I immediately got the sense that seeing their friends in handcuffs was nothing new to them at all. And that’s a really scary thought. And it’s something that I know, but to see it in that moment where it’s so clear no one is shocked.”[11] Ultimately, Joffe-Walt concludes, “I heard this from a lot of kids, the feeling that your funky little system is cool when we’re in school and all, but don’t take it and apply it to our world. You’re in over your head. If talking in circles are not the way the world does things, then Lyons is failing to prepare kids for the world they live in.”[12]

Indeed, it appears there are no easy solutions. Although the American education and criminal justice systems may not be as impenetrable as the mechanism of state control outlined in Plato’s Republic, it is still difficult to figure out how best to divert at-risk students from the school-to-prison pipeline. Combatting systemic racism is no simple task, particularly because this racism is cloaked in myths about certain students’ criminality. Furthermore, while Plato’s ideal republic had rid itself of criminals, this is not the case in the contemporary United States. It’s a reality that’s decidedly not ideal.

Bibliography

American Civil Liberties Union. “What is the School-to-Prison Pipeline?” Accessed November 9 2015. https://www.aclu.org/fact-sheet/what-school-prison-pipeline.

Amurao, Carla. “Fact Sheet: How Bad Is the School-to-Prison Pipeline.” Tavis Smiley Report. Accessed November 9, 2015. http://www.pbs.org/wnet/tavissmiley/tsr/education-under-arrest/school-to-prison-pipeline-fact-sheet/.

“Is This Working?” This American Life. October 17, 2014. Accessed November 9, 2015. http://www.thisamericanlife.org/radio-archives/episode/538/is-this-workingAct.

Plato. Republic. Translated by G.M.A. Grube. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, 1992.

Seabrooks, Reginald. “Police Officer Grabs High School Student.” New York Times. October 27, 2015. Accessed November 9, 2015. http://www.nytimes.com/video/us/100000004001301/police-officer-grabs-high-school-student.html?action=click&contentCollection=us&module=lede®ion=caption&pgtype=article.

“The School-to-Prison Pipeline.” New York Times. May 29, 2013. Accessed November 9, 2015. http://www.nytimes.com/2013/05/30/opinion/new-york-citys-school-to-prison-pipeline.html.

[1] Plato, Republic, translated by G.M.A. Grube (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, 1992), 45.

[2] Plato, Republic, 91.

[3] Reginald Seabrooks, “Police Officer Grabs High School Student,” New York Times, October 27, 2015, accessed November 9, 2015, http://www.nytimes.com/video/us/100000004001301/police-officer-grabs-high-school-student.html?action=click&contentCollection=us&module=lede®ion=caption&pgtype=article.

[4] “What is the School-to-Prison Pipeline?” American Civil Liberties Union, accessed November 9, 2015, https://www.aclu.org/fact-sheet/what-school-prison-pipeline.

[5] “The School-to-Prison Pipeline,” New York Times, May 29, 2013, accessed November 9, 2015, http://www.nytimes.com/2013/05/30/opinion/new-york-citys-school-to-prison-pipeline.html.

[6] Carla Amurao, “Fact Sheet: How Bad Is the School-to-Prison Pipeline,” Tavis Smiley Reports, accessed November 9, 2015, http://www.pbs.org/wnet/tavissmiley/tsr/education-under-arrest/school-to-prison-pipeline-fact-sheet/.

[7] “Is This Working?” This American Life, October 17, 2014, accessed November 9, 2015, http://www.thisamericanlife.org/radio-archives/episode/538/is-this-workingAct.

[8] “Is This Working?”

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.