Italy

Published: 1483 CE; 1495 CE

Matteo Maria Boiardo,

Orlando Innamorato

Written for a fifteenth-century Italian court society hooked on Arthurian romance but also attuned to current world events, Boiardo’s Orlando Innamorato (Orlando in Love) charts a complex imaginary course in which characters from diverse cultures encounter one another in ways that range from armed conflict to friendship and love.

Although knights and damsels from around the globe are gripped by a number of passions, such as erotic desire, anger, ambition, compassion, and the desire for glory or revenge, their actions are not based on either religious or ethnic differences. The narrative thereby breaks out of the polarization of Christians and Saracens typical of Carolingian epic, presenting a broader cosmopolitan vision of humankind consonant with ancient, medieval, and fifteenth-century historical and geographical texts that were capturing the attention of the Ferrarese court.

Matteo Maria Boiardo turns the Carolingian literary tradition on its head by claiming that the purportedly impeccable Orlando (Roland in the French tradition) had fallen hopelessly in love at first sight with Angelica, a Saracen princess from Cathay who appeared in Paris during an international tournament and offered herself as prize to the knight who could unhorse her brother in a joust. In his new guise as Arthurian knight errant, Orlando traverses the globe searching for his beloved and undertaking brave deeds in an attempt to win her love. Yet all his efforts are for naught: as Boiardo already anticipates in the opening stanzas, the previously invincible Orlando was a loser when it came to love (“contra ad amor pur fu perdente”; 1.1.3).

One of the most noteworthy aspects of Boiardo’s romance epic is how it continuously works against the standard opposition between Christians and Saracens that would have been taken for granted by the poem’s early readers. Although he does not refute the eventual tragic fate of Charlemagne’s rearguard in the Pyrenees, he provides an alternative vision in which Charlemagne’s knights do not fight to conquer territory or to force their religion upon others. The most positively portrayed characters across the globe are those who respect a universal code of chivalry. One such character is the Eastern queen Marfisa, whose alliance with Ranaldo at Albracà develops into a bond of friendship. When she believes that Ranaldo has been mortally wounded by Orlando, her silent weeping reveals a hidden tenderness beneath her nerves of steel: “E Marfisa tacendo lacrimava, / Perché pose Renaldo al tuto perso” [“and quietly Marfisa wept / because she thought Ranaldo lost”] (OI 1.28.27). Yet since she had promised Orlando not to intervene in the battle (OI 1.26.56), she never considers breaking her word, even though she fears losing her friend and ally. Indeed, her unconditional adherence to the chivalric code is so well known that, when she agrees to a safe-conduct for Angelica to watch the day’s battle between the cousins, everyone feels safe to move about without danger (OI 1.27.43).

The interlaced plot allows Boiardo to weave in episodes concerning additional foreign protagonists whose interests remain beyond the confines of Europe, such as the courteous Syrian king Norandino (whose name is the Italian rendering of Nur ad-Din, Saladin’s predecessor). As Orlando accompanies Angelica from Albracà back to France, he reaches a “ricco e bel paese” [“wealthy, splendid realm”] that was subject to neither “guerre o contese” [“wars nor battles”] (2.19.51). The couple thereupon encounters Norandino, the ruler of this beautiful and peaceful land, who invites Orlando to join his entourage on its way to a tournament in Cyprus even before asking the knight’s name, rank, and nationality (2.19.57-58). Boiardo thus creates a situation in which Charlemagne’s foremost paladin finds himself in the Middle East not to fight a holy war, but to participate in a tournament under a Muslim king’s banner.

Boiardo suspended his poem in 1494 citing his inability to compose poetry during Charles VIII’s invasion of Italy, and his death a few months later rendered the interruption permanent. He had recorded a comparable moment of crisis at the end of Book Two, when the offenders were not French, but Venetian troops. In this case, the opening proem of Book Three proclaimed a revival of Ferrarese court life, while the narrative found room once again for romance adventures that brought together Christians and Saracens outside the arena of war – from the Mongol king Mandricardo’s serendipitous rescue of all those imprisoned at the Fountain of the Fay, to the Spanish Saracen Fiordispina’s passion for a Christian stranger. As it stands now in its unfinished but final state, a poem celebrating the global adventures of both Charlemagne’s paladins and newly invented foreign protagonists ends with a chilling evocation of the modern day “Galli” [“Gauls”] setting “la Italia tutta” [“all of Italy”] aflame. In the poem’s concluding stanza the French army has been transformed from the defending heroes within the epic plot to the invading enemies who have taken away the voice of the poet.

Jo Ann Cavallo

Columbia University

Resources

Italian-language paperback editions

—. Orlando innamorato. Ed. Riccardo Bruscagli. 2 vols. Torino: Einaudi, 1995. Although this edition is out of print, it has an excellent introduction and notes.

—. Orlando innamorato. L’inamoramento de Orlando. Ed. Andrea Canova. 2 vols. Milan: Rizzoli, 2011. This is the most recent paperback edition and takes into account the critical edition edited by Antonia Tissoni Benvenuti and Cristina Montagnani (Riccardo Ricciardi, 1999).

Available online:

—. Orlando innamorato. Ed. Aldo Scaglione. Biblioteca della letteratura italiana.

English translations:

—. Orlando Innamorato. Orlando in Love. Trans. Charles S. Ross. Parlor Press, 2004.

—. Orlando Innamorato or Orlando in Love. Translation of Cantos I to XV and part of Canto XVI in the original meter by Canutius Guglielmus (2016-2021). Boiardo’s Masterpiece in English Verse. Rossignol Books.

—. Orlando Innamorato. Translation by A.S. Kline. Poetry in Translation. 2022.

Critical studies

Teaching the Italian Renaissance Romance Epic. Ed. Jo Ann Cavallo. New York: Modern Language Association, 2018. Several of the essays deal specifically with teaching Boiardo’s poem.

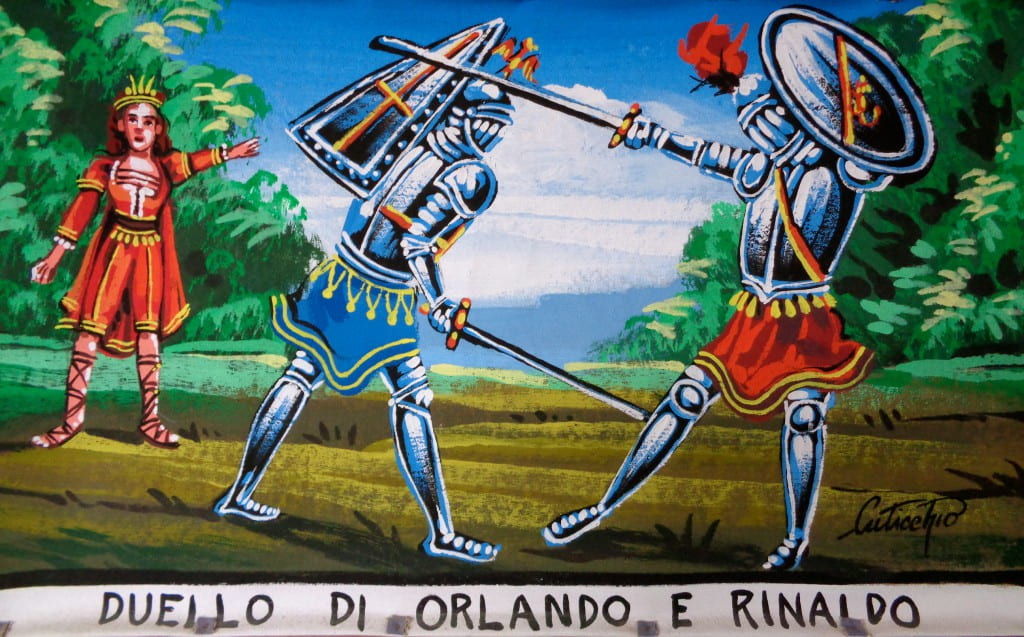

For art based on the Orlando Innamorato, see this page on eBOIARDO.

eBOIARDO

eBOIARDO showcases theatrical, musical, and artistic representations based on Boiardo’s Orlando Innamorato, Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso, and other Italian Renaissance romance epics. The bulk of the videos feature Sicilian puppet theater and the epic Maggio of the Tuscan-Emilian Apennines, including scenes from several plays and interviews with puppeteers and maggerini.

Readings from the Orlando Innamorato in Italian by Paolo Panaro (canto 1) and Charles Ross (canto 18) can be downloaded from First Lines: A Project in Global Diversity (Charles Ross, Purdue University).

eBOIARDO: videos of performances based on episodes of this epic poem

The following questions are geared toward a discussion of Boiardo’s Orlando Innamorato in the context of the upper-level undergraduate course Nobility and Civility: East and West (Columbia University global core).* A syllabus of the course can be found here.

Matteo Maria Boiardo, Orlando Innamorato/Orlando in Love, translated by Charles S. Ross (West Lafayette: Parlor Press, 2004). Princess Angelica of Cathay arrives at Charlemagne’s court in Paris and all present, including Roland (now Orlando), fall in love (1.1.1-35, pp. 3-7); Orlando fights the Tartar khan Agricane over Angelica (1.8.29-55 and 1.9.1-17, pp. 160-165); Orlando’s travel’s through Morgana’s underworld kingdom (2.8.1-2.9.29, pp. 312-324)]; Orlando and Angelica at a tournament in Cyprus (2.19.51-60 and 2.20.1-40, pp. 408-414).

The opening scene brings together for a festive occasion characters who had been at war against each other in The Song of Roland.

Roland > Orlando

Ganelon > Gano

Marsile > Marsilio

Baligant > Balugant (called King Charles’s kin [1.1.10] because in the Italian literary tradition Charlemagne had married Marsilio’s sister and Balugante was their brother).

Aude > Alda (1.1.22)

What has changed besides the Italianization of their names? What threatens the civility of the gathering before Angelica’s appearance? What might bridge the gap across diverse cultures?

Although the poem contains many instances of magic and enchantments, from the outset both Christian and Saracen knights fall hopelessly in love with Angelica without any recourse to magic on her part. Is love such an overwhelming force that it destroys agency? What are other implications of this momentous event?

In the transitional moment in which Orlando is still able to analyze his condition rationally, he is nonetheless unable to place reason over desire. Is Boiardo acknowledging the power of love by showing how it overcomes even Charlemagne’s most stalwart paladin or is he attempting to immunize the reader against Love’s irrational pull by treating Orlando’s “fall” humorously?

In the next episode included in the reading (book 1, canto 18), Orlando has already left Charlemagne’s court far behind and is in Cathay (China) fighting to defend Angelica from the Tartar (Mongol) king Agricane. Although the poem’s opening verses separate the universal compulsion to love from the more acquisitive and reckless desires of the power elite, Agricane fits both categories for what has led him to abandon his realm and undertake a large-scale war is none other than his thwarted desire to marry Angelica. When not swinging swords, the two knights engage in conversation about topics such as how one’s time is best spent and the ultimate meaning of human existence. Rather than an opposition due to two different religious creeds as in the Song of Roland (their conflict, after all, is due exclusively to their desire for the same woman), their debate could be said to contrast two forms of nobility. How might their different value scales be described?

How does Orlando make a case for learning? Why can neither maintain their civility when their love for Angelica comes into the picture? How does Agricane’s conversion compare with that of Marsile’s queen Bramimonde in the Song of Roland?

Orlando’s adventure in Morgana’s realm is certainly magical, but where might we locate elements of allegory or symbolism? Why is Orlando eventually able to succeed at each step despite initial failure?

As Orlando and Angelica travel from Cathay to France, they encounter the king of Syria Norandino (Italianization of Saladin’s predecessor Nur ad-Din) and join his entourage for a joust in Cyprus. What shared values are underpinning the civility of the setting? If love is aligned with chivalric values in the Cypriot joust, where does the threat to civility lie now?

In Boiardo’s day Carolingian epic (e.g., The Song of Roland) was considered serious while Arthurian romance (e,g., The Knight of the Cart) was considered frivolous. Boiardo, however, claims that the latter was preferable because King Arthur’s knights “displayed their worth in many battles / and sought adventure with their ladies” whereas Charlemagne’s court “closed its gates to Love / and only followed holy wars” (2.18.1-2). Is he saying fighting over love is more noble than fighting over religion? If love is so praiseworthy, then why does it also lead to loss of identity/self-control (in the opening scene) and to large-scale destruction (Agricane’s war)? How are alliances formed in the Cypriot joust episode?

Jo Ann Cavallo (Columbia University)

*This two-semester course was designed through the Faculty Workshops for a Multi-Cultural Sequence in the Core Curriculum (Heyman Center for the Humanities, 2002-2009), directed by the late Wm. Theodore de Bary, at Columbia University.