England

First published in 1671

John Milton,

Paradise Regained

Paradise Regained (1671) is a brief epic of 2,070 blank verse lines that John Milton (1608–74) published just four years after the first publication of his epic Paradise Lost (1667 in 10 books; 1674 in 12 books), an imaginative retelling of the biblical Genesis 1–3 and comprised of 10,565 blank verse lines. Milton indicates his recognition the genre of brief epic, as Barbara Lewalski and others have noted, in his prose work The Reason of Church Government (1642): “that Epick form whereof the two poems of Homer, and those other two of Virgil and Tasso are a diffuse, and the book of Job a brief model.” Having become fully blind in 1654, Milton dictated both Paradise Lost and Paradise Regained, as well as the tragedy Samson Agonistes (published under the same book covers as Paradise Regained) to amanuenses, family-members, and friends who wrote down his spoken words. One of those amanuenses was the Quaker Thomas Ellwood, who recounts in his History of the Life of Thomas Ellwood (1714) that he responded to having read a manuscript version of Paradise Lost, “Thou hast said much here of paradise lost, but what hast thou to say of paradise found?” Ellwood may have provided Milton with some encouragement for a topic that he had long considered. That topic is the biblical Jesus’ Temptation in the Wilderness, recounted in the Synoptic Gospels (Matt. 4:1–12, Mark 1.12–13, Luke 4:1–13).

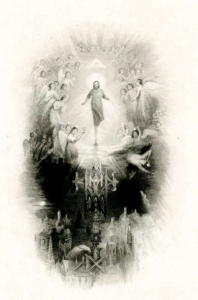

The Temptation of the Pinnacle; Christ standing in the centre, on top of pinnacle, his halo beaming, surrounded by angles, Devil defeated below to the right; after JMW Turner (Wilton 1268); title-page vignette to ‘Paradise Regained’, book IV, in ‘The Poetical Works of John Milton’ (London: John Macrone, 1835, vol. IV?). © The Trustees of the British Museum

The four books of Paradise Regained are sparse in action and external description, and rich in dialogue primarily between Jesus and Satan. Interspersed are scenes in Heaven of God “smiling” in anticipation of “This perfect man, by merit called my Son” succeeding against Satan’s temptations (PR 1.129, 166–670); the apostles Simon Peter and Andrew expressing their “plaints” at not being able to find the “Messiah” Jesus (PR 2.1–59) followed by that of Jesus’ mother Mary (PR 2.60–108); and Satan scheming in Hell (PR 1.33–118, 2.115–235). Book 1 starts in media res in accord with early modern Western epic conventions, with Jesus entering the desert for the Temptation in the Wilderness, after he is baptized in the River Jordan by John the Baptist and before he embarks on his public mission. The baptism is obsessively recounted by the narrator and different characters (PR 1.18–32, 268–89, 327–34; 2.1–12, 82–85). Jesus then undergoes the temptations, in the Lukean order—of turning stone to bread, of power over the kingdoms of the world seen in a mountain vista, and of throwing himself from the pinnacle of the Temple to be rescued by angels—all of which he overcomes by quoting Hebrew Bible / Old Testament passages. Book 4 concludes with “Satan smitten [. . .] with amazement,” “struck with dread and anguish,” and falling back to Hell; and with Jesus whisked off the pinnacle by angels who provide him with “celestial food, divine, / Ambrosial fruits fetched by the Tree of Life / And from the Fount of Life ambrosial drink” and sing “Heavenly anthems of his victory / Over temptation, and the Tempter proud” before “he unobserved / Home to his mother’s house private return[s]” in the final line of the brief epic (PR 4.562, 576, 588–90, 594–95).

Reception and translation of Paradise Regained has been limited. In eighteenth-century England, Samuel Johnson opined that Paradise Regained “has been too much depreciated.” In twentieth-century Argentina, Jorge Luis Borges vacillated in his assessment of Paradise Regained. Although he read it voraciously along with all Milton’s other works in an “Everyman’s Library edition” at the age of 15, in his maturity he wrote: “I am sorry to say, perhaps to reveal to you, that these are the last lines of Paradise Regained, ‘hee unobserv’d / Home to his Mothers house private return’d,’ the language is plain enough, but at the same time it is dead.”

I remember reading Paradise Regained for the first time as an undergraduate in the 1980s. I found it approachable because of its brevity and its allusive focus. Rather than wielding his vast storehouse of great learning, as he commonly does in his political prose and other poetry, Milton maintains in this work a sharp focus on the Synoptic Gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke, and incorporates major themes from the Gospel of John and the Bible more generally. I share an appreciation for this work with British artists William Blake (1816–20) and J. M. W. Turner (1835), who were inspired by Paradise Regained to create visual art in the nineteenth century, and the US illustrator Gary Panter, creator of the graphic novel Songy of Paradise, Wherein Satan and A Hillbilly Re-Enact The Temptation Of Jesus In The Desert, Hewing To John Milton’s Epic Poem Paradise Regained But Without Milton Verbosity (2017).

Angelica Duran

Purdue University

Works Cited

Abrams, M. H. with Geoffrey Galt Halpern. “Epic.” In A Glossary of Literary Terms, 8th edition, pp. 81–84. U.S.: Thomson Wadsworth, 2005.

The Bible: Authorized King James Version with Apocrypha, ed. Robert Carroll and Stephen Prickett (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008).

Blake, William. “Illustrations to Milton’s “Paradise Regained” (Composed c. 1816–20), The William Blake Archive, 2022, accessed August 2022.

Borges, Jorge Luis. This Craft of Verse, edited by Cȃlin-Andrei Mihȃilescu. Cambridge, Mass., 2000.

Borges, Jorge Luis, and Willis Barnstone. “Time Is the Essential Mystery.” In Borges at Eighty: Conversations, edited by Willis Barnstone, 101–12. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1982.

Ellwood, Thomas. History of the Life of Thomas Ellwood. London: J. Sowle, 1714.

Johnson, Samuel. Johnson’s Chief Lives of the Poets. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1889 [orig. 1779–81].

Lewalski, Barbara Kiefer. Miton’s Brief Epic: The Genre, Meaning, and Art of ‘Paradise Regained.’ Providence, RI: Brown University Press, 1966.

Milton, John. The Complete Poems, edited by John Leonard. New York: Penguin, 1998.

—. Poetical works; Ed. by Sir Egerton Brydges; with Imaginative Illustrations by J. M. W. Turner. England: John Macrone, 1835.

Panter, Gary. Songy of Paradise, Wherein Satan and A Hillbilly Re-Enact The Temptation Of Jesus In The Desert, Hewing To John Milton’s Epic Poem Paradise Regained But Without Milton Verbosity. Seattle, WA: Fantagraphics Books, 2017.

Resources

Recommended edition

Milton, John. The Complete Poems, edited by John Leonard, 407–62, 874–916. New York: Penguin, 1998.

Critical Studies

Flood, John. “Marian Controversies and Milton’s Virgin Mary,” in Milton and Catholicism, edited by Ronald Corthell and Thomas N. Corns, 169–94. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 2017.

Frye, Northrop. “The Typology of Paradise Regained,” Modern Philology 53, no. 4 (May, 1956): pp. 227–38

Gay, David. “The Messianic Vision of Paradise Regained.” In A Concise Companion to Milton, revised edition, edited by Angelica Duran, pp. 178–96. Madsen, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011.

Kean, Margaret. “Paradise Regained,” in A Companion to Milton, edited by Thomas N. Corns, 429–43. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2003

Knoppers, Laura. The Complete Works of John Milton, Volume II: The 1671 Poems: “Paradise Regain’d” and “Samson Agonistes. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

MacKellar, Walter, with Edward R. Weismiller. A Variorum Commentary on the Poems of John Milton, Volume 4. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1975.

Revard, Stella. “The Gospel of John and Paradise Regained: Jesus as the ‘True Light’,” in Milton and the Scriptural Tradition: The Bible into Poetry, edited by James H. Sims and Leland Ryken, 142–159. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1984.

Sauer, Elizabeth. “The Voices of Nebuchadnezzar in Paradise Regained” and “Conclusion,” in Barbarous Dissonance and Images of Voice in Milton’s Epics, 136–161, 185–190. Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1996.

The above bibliography was compiled by Angelica Duran (Purdue University) with classroom teaching in mind.

Blake, William. “Illustrations to Milton’s “Paradise Regained” (Composed c. 1816–20), The William Blake Archive, 2022, accessed August 2022.

Milton, John. Paradise Regain’d, A Poem in Four Books, to Which is Added Samson Agonistes: And Poems upon Several Occasions. The New York Public Library Digital Collections, 2022, accessed August 2022.

Milton, Poetical works; Ed. by Sir Egerton Brydges; with Imaginative Illustrations by J. M. W. Turner. England: John Macrone, 1835.

Panter, Gary. Songy of Paradise, Wherein Satan and A Hillbilly Re-Enact The Temptation Of Jesus In The Desert, Hewing To John Milton’s Epic Poem Paradise Regained But Without Milton Verbosity. Seattle, WA: Fantagraphics Books, 2017.

Suggested by Angelica Duran (Purdue University) with classroom teaching in mind.

Milton, John. Paradise Regained. The John Milton Reading Room, edited by Thomas H. Luxon, Trustees of Dartmouth College – Creative Commons License, 1997–2022. Accessed August 2022.

Related films and novels:

film Jesus Christ, Superstar!

film Godspell

Jim Crace’s novel Quarantine (1998)

film Last Days in the Desert (2015; Dir. Rodrigo García, starring Ewan McGregor)

Suggested by Angelica Duran (Purdue University) with classroom teaching in mind.

Milton, John, and Anton Lesser. “Paradise Regained,” Naxos, Overdrive, 2022, accessed August 2022.

Rogers, John. “21. Paradise Regained, Books I–II, YaleCourses, YouTube, November 2008, accessed August 2022.

Rogers, John. “22. Paradise Regained, Books III–IV, YaleCourses, YouTube, November 2008, accessed August 2022.

Suggested by Angelica Duran (Purdue University) with classroom teaching in mind.