England

Published: 1667 in 10 books, 1674 in 12 books

John Milton

Paradise Lost

Paradise Lost emerged from the crucible of England’s Civil Wars, Interregnum, and Restoration, as well as the author’s life. John Milton (1608–74) had been blind for over a decade before its first publication and thus orally recited what was to become his 10,565-line epic to amanuenses, family-members and friends who wrote down his spoken words.

He survived the retributive executions by the English monarchy upon the Restoration, through King Charles II’s Act of Free and General Pardon, Indemnity and Oblivion (1660), despite his decade-long role as Secretary of Foreign Tongues for the ousted interregnum government (1649–60), which had overthrown and beheaded King Charles I.

Further, a number of London presses rejected the epic before Samuel Simmons published it in a slim volume with no illustrations. Since then, many readers have encountered obstacles with its meter; its layers of rich allusions, to the Bible and Christianity no less than to Greek and Roman mythology, as well as to ancient and Renaissance epics; and increasingly its early modern English language. Yet, English literati were quick to pen encomiums for the work, and it has become a foundational component of world literature and a beloved text for many, as expressed from Andrew Marvel’s ode “On Mr. Milton’s ‘Paradise Lost’” (1674) to Sandra Fernandez Rhoads’s young adult fantasy fiction Mortal Sight (2020).

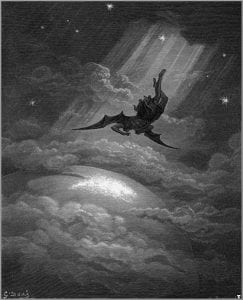

The story’s rich characters and actions combine with Milton’s poetic craft to account for the fascination it has produced in its many readers around the globe and across centuries, including many visual artists like France’s Gustave Doré—one of his 50 illustrations, originally published in an Anglophone Paradise Lost (ca. 1866), graces this webpage as it does translations into Arabic, Chinese, Finnish, German, Japanese, Portuguese, Russian, and Spanish, to name just a few. Book 1 starts “into the midst of things” (PL 1.Argument), that is, in media res in accord with early modern Western epic conventions, with Satan and the fallen angels awaking in a tremendously dire Hell after their rebellion and three-day War in Heaven against God the Father, the Son, and the good angels. In a fine use of epic flashback in Books 5 and 6, the archangel Raphael describes that cosmic war to the first humans, Adam and Eve. What is fresh and unconventional in Paradise Lost is the subtle, modern characterization of the fallen angels, good angels, first humans, and even the deity. Adam and Eve display the full range of human emotions from gratitude to God for their being, their place, and each other, to the bitter acrimony that follows, first, Eve’s eating of the interdicted Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil after being tempted by Satan disguised as a serpent, then, Adam doing so upon being tempted by the fallen Eve in Book 9. The repercussions for their disobedience to God’s single prohibition are immediate in Eden and globally: Adam and Eve objectify and insult each other; the Son curses the serpent with human enmity, Eve with subordination and pain in child birth, and Adam with hard labor to eke out food and life, and he clothes the couple’s once-glorious nakedness in animal skins, in accordance with Genesis 3.14–21; and Milton represents other aspects of the fallen world, such as predatory bestial behavior, intemperate climate, and the departure of the many angels who once inhabited the Earth. Yet, the last three Books figure hope amid a realistic if theological world-view. Adam and Eve reconcile in Book 10, and their prayers of repentance at the end of the Book reach Heaven at the beginning of Book 11. Through the intercession of the Son, God the Father accepts their prayers and sends the archangel Michael to “Dismiss them not disconsolate” (PL 11.113) before ousting them from Paradise. Michael does so in part by providing Adam with, first, a biblically-based vista (Book 11), then a verbal account (Book 12) of the course of human history. Eve is consoled through a dream, as she recounts in the last human lines spoken in the epic.

M. H. Abrams defines epics as having a “setting that is ample in scale [. . .]. The scope of Paradise Lost is the entire universe, for it takes place in heaven, on earth, in hell, and in the cosmic space in between.” Clearly, Milton’s imaginative creativity was impelled by the dynamic age in which he lived, the first in which the whole of the globe was first navigated and conceptualized through the astronomical findings of Galileo and others—the latter is captured in the telescopic vision of the Earth as a “watery glass” during the archangel Michael’s account of the Flood (Genesis 6–9) at the end of Book 11.

Readers have been rightly impressed by the work’s sheer depth of human concerns and its imaginative breadth: its domestic scenes—from love-making to lunching—and its panoramas—from the politically-resonant scenes of God the Father’s “armèd saints / By thousands and millions” (PL 6.47–48) battling in the War in Heaven to the “innumerable swarm” of fish during Creation (PL 7.400) to the moving catalogue of human illness and violence in the last two Books—all leading to the ambivalent closing scene of Adam and Eve exiting Eden “hand in hand with wand’ring steps and slow” (PL 12.648).

Angelica Duran

Purdue University

Works Cited

Abrams, M. H. with Geoffrey Galt Halpern. “Epic.” In A Glossary of Literary Terms, 8th edition, pp. 81–84. U.S.: Thomson Wadsworth, 2005.

Milton, John. The Complete Poems, edited by John Leonard. New York: Penguin, 1998.

Resources

Editions:

Milton, John. The Complete Poems, edited by John Leonard. New York: Penguin, 1998.

Critical studies:

Abrams, M. H. with Geoffrey Galt Halpern. “Epic.” In A Glossary of Literary Terms, 8th edition, pp. 81–84. U.S.: Thomson Wadsworth, 2005.

Blessington, Francis C. “Paradise Lost” and the Classical Epic. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1979.

Bowra, C M. From Virgil to Milton. London: Duckworth, 1945.

Campbell, Gordon. “John Milton (1608–1674). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. 2009. Accessed July 2020.

Corns, Thomas C. The Milton Encyclopedia. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012.

Danielson, Dennis. Milton’s Good God: A Study in Literary Theodicy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982.

Duran, Angelica, ed. A Concise Companion to Milton, revised ed. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011.

Duran, Angelica, Islam Issa, and Jonathan R. Olson. Milton in Translation. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017.

Evans, J. Martin. “Paradise Lost” and the Genesis Tradition. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1968.

Greene, Thomas M. The Descent from Heaven: A Study in Epic Continuity. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1975.

Hale, John. Milton’s Languages: The Impact of Multilingualism on Style. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

Lewalski, Barbara K. The Life of John Milton. Malden: Blackwell, 2000.

Martindale, Charles. John Milton and the Transformation of the Ancient Epic. London: Croom Helm, 1986.

Tillyard, E. M. W. The English Epic and its Background. London: Chatto and Windus, 1954.

Webber, Joan. Milton and the Epic Tradition. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1979.

Wittreich, Joseph A. Feminist Milton. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1987.

The above bibliography was compiled by Angelica Duran (Purdue University).

William Blake, Illustrations to Paradise Lost (composed 1808). The William Blake Archive.

**

“Author Milton” illustrations worksheet

by Angelica Duran (Professor of English, Comparative Literature, and Religious Studies, Purdue University)

Course title and instructor:

Your name:

Your illustration:

Select your illustration of Milton after perusing at least one image from each of these three subsections:

I.

- Unknown artist (ca. 1629)

- William Marshal (1645)

- William Faithorne the Elder (after 1670)

II.

- Jacob Houbraken (1741)

- Henry Fuseli (1794)

- Unknown (first ½ of 18th century)

III.

- James Barry (1804/05)

- William Blake (1804-11)

- Unknown artist (1750-1920)

- Mihály von Munkáscy (1877)

- Thomas Beech (active 1840-73)

- Charles Courtry after Mihály von Munkáscy (c.1900)

1) Describe how the visual artist captures the following types of imagery, previously discussed in terms of the literary artist.

1A) visual, or seeing.

1B) auditory, or hearing.

1C) olfactory, or smelling.

1D) tactile, or feeling.

1E) gustatory, or tasting.

1F) kinesthetic, or moving.

2) Describe two characteristics that you ascribe to Milton and to one of the other characters represented in the illustration.

2A) Milton.

2B) _______.

3) BONUS. Consider the institution or webpage information. How does either or both contribute to representing Milton, as a world author, an artist more generally, a family member, or some other category?

4) Describe any signs of English-ness or internationalism represented in the illustration or relating to the artist or the institution where the illustration is housed.

5) Anything else?

Darkness Visible: A Resource for Studying Milton’s ‘Paradise Lost’

Paradise Lost. Columbia College, The Core Curriculum, Explorations.

Documentary:

Armando Iannucci in Milton’s Heaven and Hell – BBC Documentary (2009)

Mumford & Sons, Darkness Visible

David Gilmour, Rattle that Lock

How to Read ‘Paradise Lost’ in 7 Podcasts (2022) with Michael Ullyot from the University of Calgary, Canada.

Promiscuous Listening: A John Milton Podcast (2021–22) with Marissa Greenberg from the University of New Mexico in 11 podcast conversations with a diversity of professors

Milton with John Rogers (2014) “A study of Milton’s poetry, with some attention to his literary sources, his contemporaries, his controversial prose, and his decisive influence on the course of English poetry.” YaleCourses.