New Spain / Mexico

First published in 1798

Juan Escóiquiz,

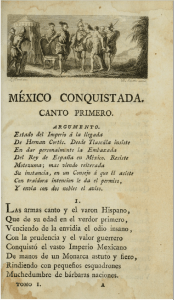

México Conquistada: Poema Heroyco

México conquistada [Mexico Conquered] is a 26-Book epic whose full title and publication information help to account for the celebratory light in which the poem represents the conquest of the Aztecs and securing of imperial power of the Americas for Spain by the Spaniard Hernán Cortés: México conquistada. Poema heroyco. Por Don Juan de Escóiquiz, Canónigo de Zaragoza, Sumiller de cortina de S. M. y maestro de georgrafia [sic] y matemáticas del Serenísimo Señor Príncipe de Asturias. Dedicado al Rey Nuestro Señor [Mexico Conquered. Heroic Poem. By Don Juan de Escóiquiz, Canon of Zaragoza, Palace Ecclesiastical to His Majesty and Master of Geography and Mathematics to the Most Serene Prince (Fernando) of Asturias. Dedicated to the King Our Lord (Carlos VII)] (Madrid: Imprenta Real [Royal Printing House], 1798).

This title rightly reflects the featured event of the European conquest of a major American people and land, not the vicissitudes of a single hero. The epic concludes with the final victory by the Spaniards and Native American partner-factions led by Cortés in 1521 and—typical of the avoidance of epic heroes’ elder life—does not follow Cortés through his death in 1547.

México conquistada obtains key features of early modern Western epic. It employs the ottava rima, the poetic stanza rhyming abababcc of Giovanni Boccaccio’s Theseid (ca. 1339–41), Torquato Tasso’s Gerusalemme liberata [Jerusalem Delivered] (1591), and other epics. The Scottish writer Tobias Smollett—who published a Spanish-to-English translation (1755, 1761) of Miguel Cervantes de Saavedra’s novel Don Quijote de la Mancha (1605)—notes the “Ulyssean cunning” of Escóiquiz’s character “la interpreta inmortal, Doña Marina” [the immortal interpreter, the lady Marina] (2.25), based on the Nahua woman who served as translator and advisor for the historical Cortés. In the mid-twentieth century, Joseph Fucilla calls attention to key resonances of La Araucana (1569) by Spain’s Alonso de Ercilla and Gerusalemme liberata by Italy’s Tasso in México conquistada. The demonization of the foe and Lucifer summoning his diabolic host in the early modern Western epic tradition certainly inform the depiction of the Native Americans in Escóiquiz’s epic.

This epic’s 3,068 stanzas, or 24,544 verse-lines, with the attendant 29-page “Prólogo” in volume 1 and “Índice de las cosas mas [sic] notables contenidas” [Index to the Most Notable Content] at the end of each of the three volumes in which the epic was published reflect Escóiquiz’s typical prolix writing style. Two relevant examples are his 1812 English-to-Spanish translation of John Milton’s epic Paradise Lost (12-Book version of 1674), which nearly doubles Milton’s 10,565 verse-lines, and his 97-page rebuttal of Tobias Smollett’s 1801 eight-page review of México conquistada, amply titled Exortación amistosa dirigida a ciertos analistas ingleses, con motivo de la crítica que hacen del poema de Juan de Escóiquiz intitulado México conquistada, por Inocencio Redondo [Friendly Exhortation Directed to Certain English Critics, Aimed at the Criticism They Make about the Poem by Juan de Escóiquiz titled ‘Mexico Conquered,’ by Roundly Innocent (pseud.)] (1804). Escóiquiz characterizes his translation El Paraíso perdido as a project of “alguna utilidad para mi patria” [some usefulness for my country], in line with the impetus of Francisco Granados Maldonado, similarly the author of an original epic—La Zaragozaida (1872)—and an English-to-Spanish translation of Paradise Lost (1858).

In the eight-page review, Smollett shows himself to be an attentive reader of Spanish, of epic, and of Escóiquiz’s poem. He provides summaries of most of the Books and about two pages of Spanish-to-English translations of passages of México conquistada in decasyllabic verse. He concludes with the following assessment: “[Escóquiz] has avoided the vices by which Spanish poetry was so long contaminated, but he cannot be ranked with the good poets of Spain”—an accurate assessment according to the author of this introduction. Even the objective, historically distanced scholar Fucilla can credit Escóiquiz for his epic only in that “[h]e evinces some skill in characterization and is fairly successful in painting a number of vivid battle scenes.”

It is worth noting that Smollett’s translations are passages describing battles (4.106–119, 5.18–20, 14.9–14), thus validating Fucilla’s assessment of Escóiquiz’s success at depicting martial skill and valor. The scenes are to be expected since, in the opening invocation, the epic narrator ascribes violent tendencies to Native Americans, calling them a people “Culta y guerrera” [Cultured and bellicose] (1.11). The ascription of full humanity, much less the capacity to be cultured, to Native Americans was still only gaining traction in Enlightenment Europe. Escóiquiz represents the martial abilities of both sides as high, even though the narrative voice and divine machinery certainly represent the Spaniards as favored by God’s “irrevocable / Voluntad” [irrevocable / Will] (15.89) and the Native Americans as on the side of Lucifer. Escóiquiz articulates the ultimate incorporation of Mexico as part of the Spanish Empire by having God announce to the angels in the penultimate Book of the epic that it is time for the battles to cease “por las armas de Hernando el Mexicano” [by the arms of Hernando the Mexican] (25.90). Whatever the historical realities, Escóiquiz can imagine humanitarian treatment of the Native Americans at the cessation of battles, in which Cortés offers clemency to the Native American leaders and populace, treatment “Digno del poderoso Soberano” [worthy of the Sovereign (God)] (26.85). He likewise uses the first formal meeting between the Aztec leader Motezuma—based on the historical figure, whose name is spelled variously, also as Moctezuma and Montezuma—and Cortés to depict the lavish beauty, excellent civil engineering, and orderly citizenry of the Mexican court and city (9.1–32).

Also worthwhile noting in México conquistada, perhaps typical of all early modern epics focused on the Americas, is the way that epic conventions gain new purchase, given their historical context and language. Escóiquiz includes the epic convention of regular descriptions of dawn reaching back to Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, such as “Como ya en el oriente aparecia [sic] / La rosada mañana” [Now that in the east appeared / Rosy dawn] (10.57). The new westernmost setting of the Americas energizes the image of eastward dawn. The multiple meaning of mañana [dawn, morning, day] increases the range of the image as signaling the short-lived novelty of New Spain in the early sixteenth century and the longer-term historical shift that this event precipitated. Escóiquiz’s original Spanish audience could have well appreciated this, given that in 1798 they were still grappling with the signal event of nearly three centuries earlier.

Angelica Duran

Purdue University

Works Cited

Escóiquiz, Juan. Exortación amistosa dirigida a ciertos analistas ingleses, con motivo de la crítica que hacen del poema de Juan de Escóiquiz intitulado México conquistada, por Incencio Redondo. Toledo, Impr. de Anguiano, 1804.

—. México conquistada. Poema heroyco. Por Don Juan de Escóiquiz, Canónigo de Zaragoza, Sumiller de cortina de S. M. y maestro de georgrafia [sic] y matemáticas del Serenísimo Señor Príncipe de Asturias. Dedicado al Rey Nuestro Señor. Madrid: Imprenta Real, 1798.

Fucilla, Joseph G. “The Influence of Ercilla and Tasso on Escóiquiz’ México Conquistada.” Hispanic Review 14, no. 1 (1946): 68–75.

Smollett, Tobias. “ART. IV.-Mexico Conquistada; Poëma Heroyco, c. Madrid. Mexico Conquered; an Heroic Poem. By Don Juan de Escoiquiz, Canon of Zaragoza, &c. In 3 Volumes.” The Critical Review, or, Annals of Literature 33, no. 2. London: S. Hamilton, 1801: pp. 513–520.

Resources

Works by Juan Escóiquiz:

México Conquistada: Poema Heroyca, 3 vols. Madrid: Imprenta Real, 1798.

Escóiquiz, Juan. Exortación amistosa dirigida a ciertos analistas ingleses, con motivo de la crítica que hacen del poema de Juan de Escóiquiz intitulado México conquistada, por Incencio Redondo. Toledo, Impr. de Anguiano, 1804.

Additional reading:

Burkholder, Mark A. “Spain’s America: From Kingdoms to Colonies. Colonial Latin American Review 25, no. 2 (2016): 125–153, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10609164.2016.1205241.

Fucilla, Joseph G. “The Influence of Ercilla and Tasso on Escóiquiz’ México Conquistada.” Hispanic Review 14, no. 1 (1946): 68–75.

Smollett, Tobias. “ART. IV.-Mexico Conquistada; Poëma Heroyco, c. Madrid. Mexico Conquered; an Heroic Poem. By Don Juan de Escoiquiz, Canon of Zaragoza, &c. In 3 Volumes.” The Critical Review, or, Annals of Literature 33, no. 2. London: S. Hamilton, 1801: pp. 513–520.

Soriano Muñoz, Nuria. “Las fisuras de la nación: tensiones y lecturas políticos-religiosas sobre la conquista de América en el siglo XVIII / The Fissures of the Nation: Tensions and Political-Religious Readings on the Conquest of American in the 18th Century.” Rubrica contemporanea 9, no.17 (2020): 11–29, https://revistes.uab.cat/rubrica/article/view/v9-n17-soriano.

The above bibliography was supplied by Angelica Duran, Purdue University.

The Fall of the Aztec Empire (The History Channel):

Exploring the Early Americas, Conquest of Mexico Paintings, U.S. Library of Congress.