Spain

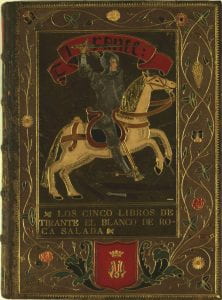

First edition, 1490

Joanot Martorell

Tirant lo Blanch

A Valencian knight named Joanot Martorell replaced his sword with a pen on January 2, 1460, in order to narrate the adventures of a fictional knight. This undertaking resulted in Tirant lo blanch, one of the most unique chivalric romances in the Hispanic literary tradition. It took Martorell four years to complete his literary project and, unfortunately, due to various financial difficulties, he lost ownership of the work in the process. Heavily in debt, the author delivered the Tirant lo blanch manuscript as a partial payment to Martí Joan de Galba, his money lender.

Martorell would not see his work again. The author died soon after, in 1465, and attempts to recover the manuscript by his brother Galcerán Martorell, himself a knight, were unsuccessful. Galba, presumably one of the first readers of the Tirant, was allured by the chivalrous and amorous adventures of the characters and handed the work over to Nicolás Spindeler, a Valencian printer, in 1490.

Just like Martorell, Galba would not see the work published, as he died before the book was in print. Galba’s submission of the draft to the printer with annotations and his subsequent disappearance probably led Spindeler to assume that the Tirant was co-authored by Martorell and Galba. Today, however, we know that the relationship between the two figures was economic rather than literary.

The work enjoyed some success in the crown of Aragon. Evidence of this is the fact that a few years later, in 1497, Diego de Gumiel printed a second edition in Barcelona. Gumiel’s role in the dissemination of this chivalric romance is all the more important if we take into account that the same printing house, after moving to Castile years later, translated the Tirant from Catalan into Spanish and published it in Valladolid in 1511. Tirant lo blanch thus became Tirante el Blanco, published as an original work rather than a translation. Regardless, the Spanish version was an utter commercial failure and there are no records of it being reprinted during the Golden Age.

Cervantes, who praised Tirante el Blanco in the episode of the priest’s scrutiny of Don Quixote’s library, saved the work from lethargy. The priest, a great reader of Tirante, goes so far as to say that the work is “a treasury of enjoyment and a mine of recreation.” Pointing to particular episodes and characters, he further explains that “by right of its style it is the best book in the world. Here knights eat and sleep, and die in their beds, and make their wills before dying, and a great deal more of which there is nothing in all the other books” (Don Quijote I, VI). Don Quixote’s author thus highlights the verisimilitude and realism of the story, as well as recognizing the work’s humorous and carefree tone. Cervantes, of course, was not wrong. With a delicate mixture of realism and humor, Martorell weaves a first-rate work in which chivalry and love are manifested at various levels, with characters who escape their conventional functions and acquire distinct psychological and individualistic traits.

Martorell presents at least five nuclei of action that order the story. The first takes place in England and revolves around Guillem de Varoïc’s chivalrous youth and reclusive old age. Varoïc saves the kingdom from the invasion of the Moors of Gran Canaria and instructs Tirant in the art of chivalry. Throughout the second node, the action takes place in the Mediterranean islands of Sicily and Rhodes. There, Tirant’s wit allows Felip de Francia to marry infanta Ricomana and ascend to the throne together, while preventing Rhodes from being conquered by the Turks.

The third nucleus of the work, the longest section containing the core of the narrative, takes place in the court of Constantinople. Tirant goes there at the behest of the emperor who is threatened by the Turks and in danger of losing his empire. The knight liberates a large part of the country with his feats of arms and falls in love with Carmesina, the heiress of Constantinople. Plaerdemavida, a cheerful young lady-in-waiting of the princess, acts as a go-between and the couple marries in secret. By means of a trick, however, the Viuda Reposada, Carmesina’s nanny, makes Tirant believe that the princess is cheating on him with Lauseta, a slave from the orchard. Upset, Tirant prepares a military operation to get away from the palace so as not to see Carmesina. Hoping to bring about a reconciliation of the couple, Plaerdemavida goes to the ships and informs Tirant of her ruse.

As Tirant is about to mend his relationship with Carmesina, the ships drift from the port of Constantinople towards North Africa, where they shipwreck. Thus begins the fourth part of the narrative. Tirant and Plaerdemavida, shipwrecked separately, each continue their journey: one at the service of a lord as a knight with great deeds of arms and the other as a handmaid to a great Muslim lady. They meet again a few years later after Tirant, who has established a friendship with King Escariano of Ethiopia, has conquered and Christianized all of North Africa.

Considering that Constantinople is in danger once again, Tirant, together with his new allies, prepares a large fleet to save the city. Thus begins the fifth and final narrative segment. The knight returns to court, where he is received with honors and consummates his love with Carmesina. He then goes on to definitively defeat the Turks, with whom he establishes a truce of 101 years. His joy, however, is short-lived. Returning from the military campaign, Tirant falls seriously ill and dies in Andrinópolis. Carmesina dies of grief shortly thereafter, as does the emperor. The narrative ends with the wedding of the empress, who is the mother of Carmesina and sole survivor of the imperial family, and Hipolit, her lover and a relative of Tirant.

The narrative is characterized by its realistic tone, the spirit of the Crusades, the human measure of its characters and the particular treatment of love, which goes beyond chivalrous conventions to explore human desire in greater depth. Critics have explored the issue of the Tirant’s influence on contemporary works such as La Celestina (1499), especially as far as the role of median characters is concerned. Clearly, Cervantes was not the only writer to recognize its literary value. Positive judgments of the work on the part of such eminent figures as Dámaso Alonso and Mario Vargas Llosa have brought this chivalric masterpiece to the attention of today’s readers.

Jesús Ricardo Córdoba Perozo

Università di Napoli “L’Orientale”

Works Cited

Cervantes, Miguel de. The History of Don Quixote de la Mancha. Ed. John Ormsby. Chicago/London: Encyclopedia Britannica, 1971.

Martorell, Joanot. Tirante el Blanco. Ed. Martín de Riquer. 5 vols. Madrid: Espasa Calpe, 1974.

—-. Tirant lo Blanc. Ed. Martín de Riquer. Barcelona: Ariel, 1990.

Resources

Catalan-language paperback edition:

- Tirant lo Blanch (València 1490). A. Hauf. 2 vols. Valencia: Editorial Tirant lo Blanch, 2005.

Spanish-language paperback and online editions:

- Tirante el Blanco (Valladolid 1511). Edited by V. J. Escartí. 2 vols. Valencia: Editorial Tirant lo Blanch, 2005.

- Tirante el Blanco, (Valladolid 1511. Original edition available online.

English translations:

- Tirant lo Blanc. Ed. D. Rosenthal. New York: Schocken Books, 1984. This is the first English translation and the best known. The most recent reprint: Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996.

- Tirant lo Blanc. The complete translation. Ed. R. La Fontaine. New York: Peter Lang Publishing, 1993.

- The White Knight. Tirant lo Blanc. Ed. R. Rudder. Available online: Gutenberg Project, 1995.

Critical studies:

- Aproximació al Tirant lo Blanc. Martí de Riquer. Barcelona: Quaderns Crema, 1990.

- Tirant lo Blanch: novela de historia y de ficción. Martí de Riquer. Barcelona: Sirmio, 1992. (Barcelona: Acantilado, 2013).

- Tirant lo Blanc: evolució i revolta de la narració de cavalleries. Rafael Beltrán. València: Institució Alfons el Magnànim, 1983.

BIbliography supplied by Jesús Ricardo Córdoba Perozo (Università di Napoli “L’Orientale”).

Iconografia Tirantiana (Joanot Martorell i el Tirant lo Blanc BVMC and BJLV).

Joanot Martorell i el Tirant lo Blanc (Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes and Biblioteca Joan Lluís Vives)