China

8th century CE

The Legend of Darkness

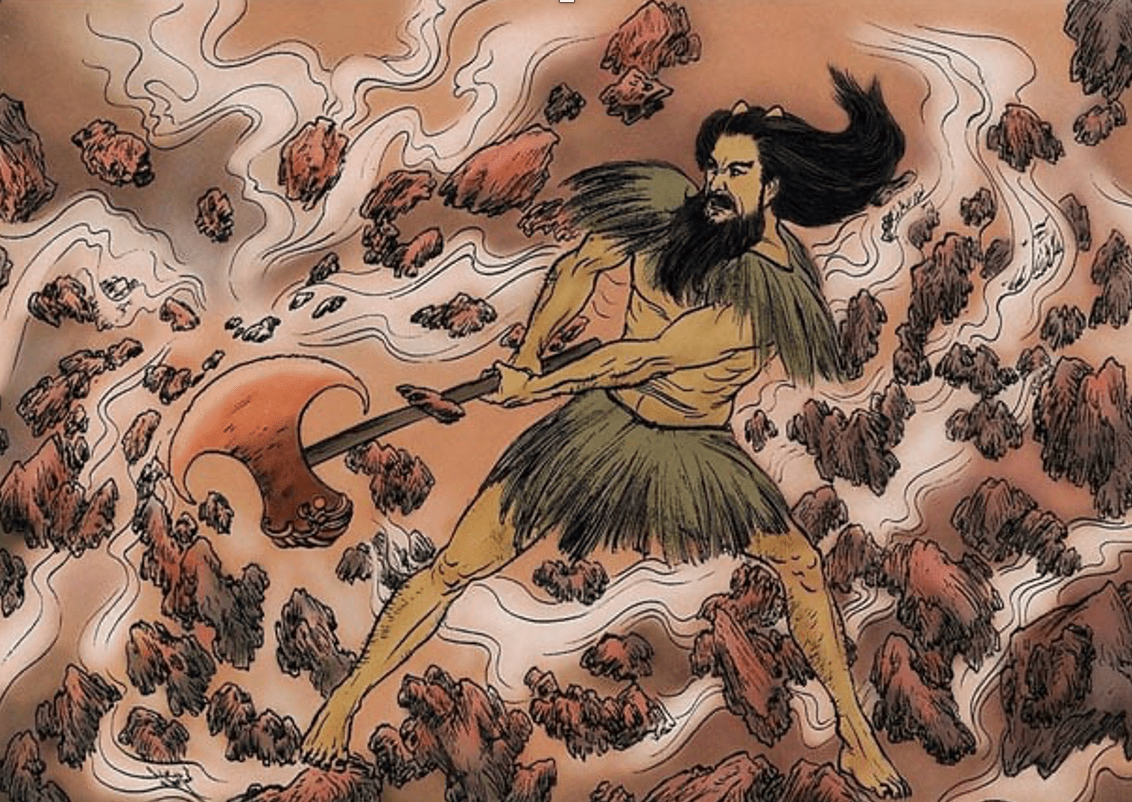

Pangu cleaving Heaven from Earth. Source: https://www.ancient-origins.net/human-origins-folklore/pangu-and-chinese-creation-myth-00347.

The Legend of Darkness is an amalgamated creation story passed down orally through untold generations among the Han people in China and likely first written down during the Tang Dynasty. Traditionally sung during funerary rites to position the deceased within the grand scope of creation, the epic is structured like a song within a song. The oral nature of the epic has allowed Han elders to preserve funerary rites in song while giving legitimacy to their age-old practices.

The Opening Song

The Opening Song always begins the epic and centers the audience in the narrative. It also contains the most variation when sung, with some versions being very short and others lasting up to three hours. Traditionally, the Opening Song would be sung by a master singer as mourners pass through the mourning gate and enter the mourning hall to celebrate the deceased.

The most common version, as captured in the H.W. Lan translation, is a metanarrative that draws the key figures together at a funeral for an undisclosed pious family. Their mourning disrupts the calm of the physical and spiritual worlds, ultimately raising the Song Tower. The audience then briefly hears the origin of the Song Tower, the progenitor of the mourning hall central to Han funerary rites. In essence, after the ancestral goddess Nuwa created humans, a singer founded the Song Tower. In response, Nuwa created roads that all terminate at the tower’s main gate.

The Song Tower is surrounded by four gates placed at the four cardinal directions. A fifth gate is located directly before the tower, granting access to its main hall. A man suddenly arrives at the center door and is interrogated with a series of questions. The man reveals that he is a singer who performs at ancestral festivals. He carries with him 3,700 songbooks with ancient compositions for all occasions. The singer also reveals an abridged version of creation, noting how the universe was formed. Those gathered urge him to tell the full story and the singer obliges.

Although the Opening Song is often shorter than the legend itself, it offers critical insight into the cultural, spiritual, and functional roles the legend plays in Han society. Death is inextricably linked to life. The moment in which a life is destroyed is thus precisely the right moment to remember the long arc of creation.

The Legend

The epic proper begins with a sort of invocation. The singer briefly foreshadows what is to come and exclaims that “the song is about ancient times and the present moment” (31). This clearly establishes the epic as omnirelevant and, seemingly, as a song to which lyrics are constantly being added. The interrogation from the Opening Song is not absent from the legend itself. Throughout the narrative the audience periodically interjects with questions intended to verify the singer’s accuracy and, thereby, his authority. These questions are modeled after the “Heavenly Questions” posed in the Songs of Chu (circa 4th century BCE).

The singer tells of the time before creation. Taiji (universe) emerged from Wuji (infinity). This time is shrouded in mystery: “They were shelled like an egg, with layers upon layers of covering, wrapped up tightly. Who can know their very beginning?” (121). If the origins of the universe are unknown, the story of creation, on the other hand, is perhaps too well known. Likely the result of a patchwork of incomplete oral creation stories, The Legend of Darkness’s narrative is at times muddled and incoherent. Time bends in on itself amidst tellings and re-tellings that seemingly contradict one another. But the intent is clear – creation is cyclical.

The first period of creation attests to a previous time, perhaps some intimate awareness among the Han people that Chinese civilization dates back to deep antiquity. Xuanhuang is the first immortal born into a universe ruled by Chaos and without light. This curious figure, largely left out of the more commonly known creation story centered around Pangu, is likely a manifestation of Yin and Yang. Xuan huang is translated as “dark and yellow,” contrasting colorations often associated with Yin and Yang. Moreover, the colors are also associated with Heaven and Earth as seen in the Thousand Character Classic (circa 6th century CE) which opens with the line “tian di xuan huang” [“heaven and earth, dark and yellow”]. Xuanhuang is probably a relic of an earlier mythological tradition as recounted in the mystical text Huainanzi (circa 2nd century BCE).

Following the birth of Xuanhuang, Qimiao is born when colorful clouds touch the five primordial mountains (the Wuyue). Together the two companions help bring order to the universe, separate heaven from earth, appoint the five directions and their associated colors (east – green; west – yellow; south – red; north – white; center – black), and tame Chaos’ beast. They also create Niyinzi, a proto-human made from clay. Yet just as the early immortals begin to establish themselves, Xuanhuang issues a warning: a cycle of floods and famines are destined to destroy the universe. Niyinzi is entrusted with the magical water gourd of life and hidden away in a cave while the other immortals are left to fend for themselves. Cosmic floods rage for 18,000 years in successive waves of red water, black water, and finally clear water. All creation is undone, “but time and again life follows calamities” (115).

This second creation mirrors the first but offers alternative explanations for the universe’s creation. The creator deity Pangu is born from Xuanhuang’s skull, equipped with the omniscience of his forbearer. Using the celestial axe, he cleaves heaven from earth by striking the ancestral Mount Kunlun. He releases qi into the universe by destroying the five Black Dragons, unleashes the Sun and Moon, and creates the oceans by eradicating Chaos’ monster, the Eagle Dragon, and the fire birds. He also convinces the Sun and Moon to join him in the heavenly court and thus finally brings light to the universe.

Niyinzi and the immortals later find a large gourd adrift on the receding floodwaters. Inside they discover a boy and a girl destined to birth humanity. Curiously, the human race is not only a product of incest, but the song explicitly grapples with the taboo nature of this origin. The immortals urge the twins to marry but the girl forcefully protests, proclaiming it improper for siblings to wed. She is persuaded when the immortals reveal that only their offspring can maintain stability and keep Yin and Yang in balance.

Fuxi and Nuwa, the first humans, are born to the twins. Echoing Niyinzi’s formation in the prior creation period, Nuwa forms humanity from sediment left behind by the floods. This sediment is said to carry the essence of life because it contains the bones of the antediluvial immortals. Thus, the sediment, and by extension the human body, is one more connection to the prior creation as the immortals killed in the flood essentially sacrifice themselves to enable rebirth. Nuwa added her own blood to the clay figures to give birth to humanity.

Nuwa’s creations are almost immediately endangered when Gonggong, the Han flood god, cracks the pillar of heaven in a fit of rage. Nuwa gathers the immortals and her human creations into a ship built from Pangu’s axe handle as the universe floods once again. Yet a wave capsizes the boat, plunging some into the waters and transforming them into aquatic creatures. Still others are cast into the air and become birds, bats, and flying insects.

The third creation is a continuation of the second. Nuwa vanquishes Gonggong and meticulously mends the heavenly column with stone, saliva, and her chilling breath. Nuwa gives her life to stem the tides. She thus becomes the Earth Mother, and “her soul keeps nourishing her offspring from generation to generation” (287). Rather than create again, Nuwa literally reinforces the prior creation. The rest is (pseudo)history. Following the final flood, humans settle the earth and restore balance to the universe through their discovery of fire, the invention of writing, the innovation of music, the advent of agriculture, and, most importantly, the ascension of an emperor. The epic ends with a genealogy of China’s legendary rulers, the Three Sovereigns and Five Emperors.

Conclusion

The Legend of Darkness is a remarkable epic that is far more complex than your average creation story. The myth’s very structure is a novel approach to cultural preservation. The metanarrative ties present funerary rites to the antiquity of creation while offering countless explanations for the Han people and their culture. The periodic interjections of the audience into the story only serve to uphold the authority of the singer and further justify the traditions for which he lays the groundwork. Yet the explicative foundations for Han cultural touchstones (although numerous and beautifully woven) are perhaps the least compelling aspect of the epic.

There is a hyperawareness throughout the narrative that creation is not confined to the ethereal realm of the immortals. Rather, creation is also generated from the earthy, alluvial, landscapes that contain all the mystery and power of the heavens. In some respects, particularly the sediment responsible for humanity’s original form, heaven and earth are one and the same. The two are inextricably linked for all time.

The Legend of Darkness is not a single flood myth but a series of flood myths. The successive creations of Xuanhuang, Pangu, and Nuwa attest to the Han people’s understanding that life is cyclical and there was not just one era before their own, but many. And these eras, moreover, are critically connected. From Pangu being born from Xuanhuang’s skull to Nuwa relying on Pangu’s axe handle to save creation, destruction is never absolute nor is creation ever born from nothing.

China’s future, the legend intimates, will forever be indebted to its past. The final lines act as a hopeful entreaty to never stop singing this song: “There was so much rise and fall, left for later generations to ponder upon. There were so many heroes, famous for striving for the throne. Common people talk about all of these, and the Song Tower is where they sing about their stories” (387).

Demetrios Kavadas

City Living NY

Works Cited

Lan, H.W. (2019). The Legend of Darkness. Wuhan: Wuhan University Press.

Resources

Translation:

Lan, H.W. (2019). The Legend of Darkness. Wuhan: Wuhan University Press.

Secondary reading:

An, Wu Bing’ (2011). “Chinese Creation Myths: A Great Discovery.” In China’s Creation and Origin Myths. Eds. Mineke Schipper, Shuxian Ye, and Hubin Yin. Leiden: Brill Publishing.

Birrell, Anne (1993). Chinese Mythology: An Introduction. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Goldin, Paul R. (2008). “The Myth that China has No Creation Myth.” Journal of Oriental Studies, 56(1), pg. 1-22.

Wang, Qian (2012). “Phenomenological Interpretation of Chinese Creation Myth of Pangu.” Theoretical Studies in Literature and Art, 32(3), pg. 134-137.

Xiaodong, Wu (2011). “Pangu and the Origin of the Universe.” In China’s Creation and Origin Myths. Eds. Mineke Schipper, Shuxian Ye, and Hubin Yin. Leiden: Brill Publishing.

Related reading:

“The Heavenly Questions” in the Songs of Chu by Qu Yuan (PDF).

Huainanzi by Liu An (PDF).

The above bibliography was supplied by Demetrios Kavadas (City Living NY).

Yin and Yang, the likely embodiment of the earlier creator deity Xuanhuang.

Mount Kunlun, the backdrop of creation. “Mount Kunlun” by Fu Baoshi (1904-1965), ink on paper.

Nuwa and Fuxi, creators of humanity. Artist unknown, Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE), painted silk.

Shennong, one of the legendary emperors and the founder of agriculture. “Shennong” by Guo Xu (1503), ink on paper.

Pangu (2019) by Taiko Studios.

The Legend of Darkness at a glance (Webpage).

Pangu (2019) by Taiko Studios (Short Film).