Turkey, Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan

Oral tradition: 9th-10th century CE

Earliest written versions: late 13th century – 14th century CE

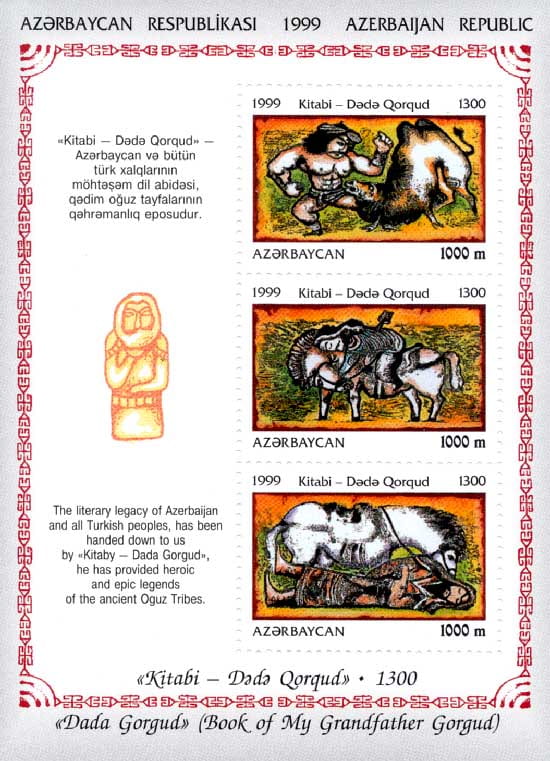

The Book of Dede Korkut

In the history of world epics, The Book of Dede Korkut stands out not only for its unique interweaving of Turkic myth, heroic narrative, and tribal ethics, but also for the layered complexity of its textual emergence. As with the Iliad, Beowulf, or The Epic of Manas, its journey from oral performance to manuscript form reveals as much about the changing sociopolitical worlds that received it as about the nomadic culture that produced it. However, unlike those epics, The Book of Dede Korkut resists singularity. It survives not as a definitive text but rather as a shifting network of tales, declamations, and myths—compiled, redacted, and interpolated by a series of unknown figures, shaped and reshaped by the political, religious, and cultural needs of successive communities.

Composed by and for the Oghuz Turks—a loosely organized confederation of Turkic tribes—the tales of Dede Korkut were passed down through generations of tribal bards (ozan), whose performances combined martial epic with aphoristic wisdom. These tales celebrate warriors who upheld the honor of their lineage, defended their households and khans against infidel raiders, and lived according to the customs of a society that viewed fortune not as entitlement but as a fragile and fleeting gift. Embedded in this worldview is the figure of Dede Korkut / Korkut Ata himself: at once sage, soothsayer, and bard, he functions as narrator, legitimizer, and communal conscience. Yet even this figure is unstable, hovering between the folkloric, the mythical, and the Islamic. In the tales, he appears as an Islamic miracle-worker and cultural lawgiver; in the declamations, he seems closer to the anonymous bard who “knows the generous man and the stingy man,” wandering from prince to prince with his lute in hand (Lewis 1974, 192).

The textual framing of the tales, especially in the Dresden manuscript, reflects the political motivations of its time. Likely copied in the sixteenth century from a fifteenth-century substratum, the Dresden manuscript contains a prose prologue and twelve narrative tales. The prologue opens with the following prophecy: “In time to come the sovereignty will again light on the Kayı and none shall take it from their hands until time stops and the resurrection dawns” (Lewis 1974, 190). The Kayı tribe, claimed by the Ottomans as their ancestor, becomes the vehicle of a dynastic theology. This ideological framing is best understood within the political context of the post-Ankara crisis of the early fifteenth century, when Ottoman sovereignty was fractured by Timur’s invasion. As Beatrice Forbes Manz has shown, Timur sought to reassert Chinggisid authority across the Islamic world, prompting the Ottomans to look backward—to the Oghuz epics—as a means of forward legitimation (Manz 1998, 25).

The tales that follow are situated around the symbolic court of Bayındır Khan, a shadowy but constant figure who serves as the paramount leader of the Oghuz tribes. While he rarely acts directly in the tales, Bayındır Khan functions as a symbolic suzerain, convening tribal councils, organizing tournaments, and judging disputes. His name likely derives from the Bayındır tribe, one of the twenty-four clans of the Oghuz as recorded in “Oghuzname” genealogies, but in the tales he appears as a supra-tribal figure—a khan of khans, around whom the values of the epic universe orbit.

The true protagonists of the tales are the warrior-nobles who embody the virtues of Oghuz aristocracy. Among them, Salur Kazan stands foremost. As chief of the Salur clan and the most frequently recurring character, Kazan is both a military leader and a moral exemplar. He is known for his generosity, martial prowess, and deep loyalty to his family and tribe. Several tales revolve around his household—his hunting accidents, his son’s coming of age, his family’s capture by enemies—and in each case, Kazan must restore order through courage, sacrifice, and the reassertion of tribal custom. He is a character of contradictions: revered yet vulnerable, powerful yet constantly tested. In many ways, he is the narrative embodiment of tribal leadership under siege.

Bamsı Beyrek, the protagonist of the third tale, “Story of Bamsi Beyrek of the Grey Horse,” is the epic’s romantic hero. His story is shaped by themes of betrothal, captivity, and return. After being promised to Banu Chichek, a noble warrior-maiden, he is captured and held for sixteen years, returning at last in disguise to test his bride’s loyalty. His tale combines elements of courtly love, endurance, and performative disguise. As in Homer’s Odyssey, recognition is postponed, and the hero must reclaim not only his name but his place within the social order. Beyrek’s tale also introduces a self-reflexive commentary on the bardic profession. Disguised as a minstrel, he is treated with disdain by the Oghuz nobles—an ironic twist that reflects the complex status of performers in tribal society. As he remarks, “The bard roams from land to land, from prince to prince, carrying his arm-long lute; the bard knows the generous man and the stingy man” (Lewis 1974, 192).

Basat, the hero of the eighth tale, “How Basat Killed Goggle-eye,” is perhaps the most mythic in character. Raised by wild animals and later adopted into human society, Basat must battle Tepegöz, a monstrous one-eyed giant who threatens to annihilate the Oghuz. Tepegöz, born of a supernatural mother and human father, cannot be killed by conventional weapons. Basat triumphs only through trickery, blinding the creature and striking with a magical sword. The tale borrows heavily from universal monster-slaying motifs and invites comparison with the Cyclops episode in Homer’s Odyssey. Yet even here, the purpose remains consistent: restoring social and moral order through individual self-sacrifice.

Other heroes—such as Uruz, the son of Kazan, or Kan Turalı, who fights a lion, a bull, and a camel to win his bride—represent different aspects of the Oghuz heroic code. They are marked by courage, filial piety, and a willingness to risk everything for honor. Their exploits often unfold in liminal spaces—mountains, rivers, enemy territory—reflecting the frontier world of the semi-nomadic Turkmens who composed and circulated these tales.

The twelfth and final tale, “The Story of How the Outer Oghuz Rebelled Against the Inner Oghuz and How Beyrek Died,” breaks from the episodic pattern and presents a narrative of civil strife between the Inner Oghuz (Bozok) and Outer Oghuz (Üçok). The war begins over a violation of the etiquette of plunder—a symbolic breakdown of tribal protocol—and escalates into a conflict that threatens the very fabric of Oghuz unity. The tale offers a grim reflection on internal discord, and its resolution is tentative at best. The division between Bozok and Üçok is rooted in the genealogical myth of Oghuz Khan, who divided his sons into two lines of descent. According to Kemal Eraslan’s philological reading, the terms denote spatial relationships within a tribal cosmology: “töz-ok” (inner arrow) and “uç-ok” (outer arrow), terms that in time evolved into names of dynastic factions (Eraslan 1986).

Throughout the book, the voice of Dede Korkut punctuates the tales with blessings, laments, and oracular pronouncements. The declamations in the prologue—rich with ethical maxims—provide a framework for interpreting the tales. These aphorisms reflect the fatalism of a society accustomed to sudden loss and violence: “Though you dress a captive girl in a robe, she does not become a lady… worn cotton does not become cloth; the old enemy does not become a friend” (Lewis 1974, 191). Other passages praise generosity, denounce greed, and warn against the folly of accumulating wealth in a world where “a man can eat no more than his portion” (Lewis 1974, 190).

The Dresden manuscript was first identified in the Dresden Library by the German orientalist Henricus Orthobius Fleischer in the nineteenth century. However, it was Heinrich Friedrich von Diez who first introduced The Book of Dede Korkut to European audiences. In 1815, Von Diez published a German translation of the eighth tale, “The Story of Basat and Tepegöz,” along with a comparative commentary that suggested a connection between the Oghuz Cyclops and Homer’s Polyphemus. His Romantic enthusiasm for discovering Eastern precursors to Western classics framed the tale within broader debates on the origins of epic literature.

The Book of Dede Korkut was little known within the Ottoman Empire until the early twentieth century. In 1916, Kilisli Rifat published the first printed edition of the text in Istanbul as part of the wartime nationalist initiative to reassert Turkish cultural heritage. Interest revived in the mid-twentieth century. Muharrem Ergin’s editions and translations helped establish a scholarly foundation, while Ettore Rossi’s discovery of the Vatican (V) manuscript in 1950 confirmed the existence of alternative textual lineages. The two manuscripts differ substantially in language, structure, and interpolations, reflecting different scribal and possibly ideological agendas. In 2001, Semih Tezcan and Hendrik Boeschoten published a side-by-side edition of the D and V texts, enabling comparative philological study. The 2018 discovery of the Gümüştepe (Gumbet) (G) manuscript in northern Iran added further depth. Though brief—comprising only two tales and a cluster of declamations—the G manuscript offers variant versions not preserved elsewhere, including a previously unknown episode about Kazan’s naming (Shahgoli et al. 2019; Azemoun 2020).

In 2018, UNESCO inscribed The Book of Dede Korkut on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. This international recognition—shared by Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Turkmenistan—confirms the text’s enduring significance not only as a work of literature but as a site of cultural memory and collective imagination. And yet, as Walter J. Ong reminds us, the act of “inscription” is also a kind of entombment: the text endures, but in doing so, it ceases to live in the way its bards once intended (Ong 2005, 80). What remains is not just an epic but a palimpsest—a text overwritten by generations of performers, compilers, and copyists, each seeking to preserve and reshape a tradition whose vitality lay in its mutability. To read The Book of Dede Korkut today is to enter not a single story but a network of voices, values, and anxieties.[1] Its heroes still ride, not just against the enemies of the tribe, but against forgetting.

[1] For a guide to reading—and teaching—The Book of Dede Korkut, see Pelvanoğlu 2023.

Emrah Pelvanoğlu

Yeditepe University, Istanbul (Turkey)

Works Cited

Azemoun, Youssef. “The New Dädä Qorqut Tales from the Recently-Found Third Manuscript of The Book of Dädä Qorqut.” Journal of Old Turkic Studies 4/1 (2020): 16–27.

Eraslan, Kemal. “On the Names of Oghuz Branches Boz-Ok And Üç-Ok.” Türk Dili Araştırmaları Yıllığı – Belleten 34 (1986): 1–4.

Kilisli Muallim Rifat. Kitab-ı Dede Korkud Alâ lisan-i taife-i Oğuzân. İstanbul: Matbaa-i Amire, 1916.

Lewis, Geoffrey. The Book of Dede Korkut. Harmondsworth: Penguin Classics, 1974.

Manz, Beatrice Forbes. “Temür and the Problem of a Conqueror’s Legacy.” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 8 (1998): 25.

Ong, Walter J. Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word. London & New York: Routledge, 2005.

Pelvanoğlu, Emrah. “Epic Tales, Ethics Codes, and Evidence of Legitimacy: The Intriguing Case of The Book of Dede Korkut.” In Teaching World Epics, ed. Jo Ann Cavallo. New York: Modern Language Association, 2023. 121-32.

Shahgoli, Nasser Khaze, et al. “Dede Korkut Kitabı’nın Günbet Yazması: İnceleme, Metin, Dizin ve Tıpkıbasım.” Modern Türklük Araştırmaları Dergisi 16/2 (2019): 147–379.

Resources

Recommended Editions:

Geoffrey, L. (1974), The Book of Dede Korkut, London: Penguin Books Ltd.

Sümer, F., Ahmet E. U. and Warren S. W. (1991), The Book of Dede Korkut: A Turkish Epic, Texas: University of Texas Press.

Critical Studies:

Adil, N. (1990) A Critical Analysis of the Theme of the Heroic Ideal in Beowulf and The Book of Dede Korkut, Ankara: Hacettepe University.

Anikeeva, T.A. (2019), “The Oghuz Epic Stories in the Seljuk Era”, History, Archeology and Ethnography of the Caucasus, 15/2, 110-117.

Azmun, Y . (2020). “The New Dädä Qorqut Tales from the Recently-Found Third Manuscript of the Book of Dädä Qorqut”, Journal of Old Turkic Studies, 4/1, 16-27.

Başgöz İ. (1978), “Epithet in a Prose Epic: The Book of My Grandfather Korkut”, in Studies in Turkish Folklore Studies of Turkish Folklore (Ed. Ilhan Basgöz and Mark Glazer), Bloomington, 24-45.

Burrill, Kathleen R. F. “Karajuk, Mini-Hero of a Dede Korkut Story,” in Proceedings of the Thirty-First International Congress of Human Sciences in Asia and North Africa (Edited by Yamamoto Tatsuro), Tokyo: Toho Gakkai, 541-542.

Can, D. T. and Metin E. (2010), “The Book of Dede Korkut: The Villains In and Out of Turks”, in Villains, Heroes or Victims? (Edited by Dana Lori Chalmers), Oxford: Inter-Disciplinary Press.

Conrad, J. A. (1999), “Polyphemus and Tepegöz Revisited A Comparison of the Tales of the Blinding of the One-eyed Ogre in Western and Turkish Traditions”, Fabula, 40/3-4, 278–297.

Dankoff, R. (1982). “‘Inner’ and ‘Outer’ Oğuz in Dede Korkut”, Turkish Studies Association Bulletin, 6/2, 21-25.

Düzgün, H. T. (2009) “The Alp (Hero) and The Monster in Beowulf and The Book of Dede Korkut”, Hacettepe Üniversitesi Türkiyat Araştırmaları (HÜTAD), 11/11, 109-117.

Hamarat, S. (2019) Cultural Norms in the Translation of Dede Korkut Stories into English, Master Thesis, Ankara: The Institute of Social Sciences at Gazi University,

İz, F. (1991), “Dede Ḳorḳut”, in Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition (Edited by P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs.), Leiden: Brill Academic Publishers.

Meeker, Michael E. (1992), “The Dede Korkut Ethic”, International Journal of Middle East Studies, 24/3, 395–417.

Mirabile, P. (1990), The book of the Oghuz peoples, or, Legends told and sung by Dede Korkut, Paris: Voies Itinerantes.

Özkartal, M. (2012), A General View Over Animal Symbolism in Turkish Epics (Samples from the Book of Dede Qorqud). Milli Folklor , 58-71.

Rzasoy, S. (2010) “The Book of Dede Gorgud: A Masterpiece of Epic Literature”. (Date Accessed: 03.07.2020)

Sümer, F., Ahmet E. U. and Warren S. W. (1991), The Book of Dede Korkut: A Turkish Epic, Texas: University of Texas Press.

Taşdelen V. (2015), “On the Meaning of Name in Plato’s Cratylus Dialogue and the Epic Tales of Dede Korkut”, Journal of Arts and Humanities, 4, 71-81.

The above bibliography was provided by Emrah Pelvanoglu, Yeditepe University, Turkey.

Dede Korkut Kitabı’nın Dresden Şehir Kütüphanesi nüshasından bir sayfa. The front page of the 16th century Dresden Manuscript.

Heritage of Dede Qorqud / Korkyt Ata / Dede Korkut, epic culture, folk tales and music. Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Kazakhstan. Inscribed in 2018 on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, UNESCO. This website contains information and short videos (including performance) concerning the heritage of Dede Korkut.