Ireland

11th century (earliest extant version)

Anonymous,

Táin Bó Cúailnge

Táin Bó Cúailnge (‘The Cattle Raid of Cooley’) is a complicated work. While its plot is relatively simple, it is difficult to introduce, especially as an epic, because of its textual history and treatment in scholarly circles. The Táin is the centerpiece of the early Irish Ulster Cycle, a group of stories dealing with the court of Conchobor (the king of the Ulaid, or the Ulstermen), the heroic deeds of Cú Chulainn, and the interactions of the Ulaid with the four other kingdoms of Ireland (particularly that of Connacht). Set in pre-Christian Ireland but at the beginning of the Christian era (roughly around the first century), the Táin tells the tale of Cú Chulainn’s single-handed defense of Ulster against the combined forces of Connacht, Leinster, and Munster, alongside a handful of Ulster exiles. The purpose of this army, led by Medb and Ailill (the queen and king of Connacht), is to take possession of the brown bull of Cooley (an otherworldly beast who was once a shape-changing swineherd) to complement another bull owned by Ailill. (These raids were such an important social institution that tána bó were a common literary genre.)

The Ulaid, meanwhile, are unable to fight because they are suffering from a curse that debilitates them with the pangs of childbirth for five days whenever their martial prowess is most needed. This leaves the precocious, seventeen-year-old Cú Chulainn—who is exempt from the pangs because he was born elsewhere—to protect all of Ulster, and much of the tale narrates his guerrilla warfare tactics and single combats as a means of stalling for the Ulaid. Ulster prevails once the men can come to battle, but the narrative ends with the death of the two bulls from fighting one another, their dismembered body parts strewn about the landscape, and a final truce between the armies.

There are three extant recensions (versions) of the Táin, and the earliest of these (found in Lebor na hUidre) is from the eleventh century. Some form of the tale, however, likely existed in the seventh century. This is corroborated by Verba Scáthaige (‘The Words of Scáthach’), a brief account that alludes to Táin Bó Cúailnge and which is believed to have been contained in the now lost eighth-century manuscript Cín Dromma Snechtai. How the tale developed—in oral or written tradition—during the intervening years is not entirely transparent, though Recension 1 is clearly a compilation of earlier sources (much of which is datable to the ninth century). Recension 2 (found in the Book of Leinster) is a twelfth-century reworking of Recension 1 with modernized language, several additions (including the famous “Pillow Talk” between Ailill and Medb that provides the impetus for the raid), and a smoother literary style. One other notable aspect of the Táin’s textual history is the existence of a number of rémscela (‘fore-tales’) that are necessary background to understand the events in the narrative, including, for example, the birth tales of Conchobor and Cú Chulainn. While these tales do not necessarily precede the Táin on the manuscript page, they revolve around its narrative—taken for granted by the redactor(s) and even collated in tale lists by the time of the Book of Leinster.

Ways of reading the Táin have gone through a number of developments over the years. Some early scholarship sought to understand the text as a “window on the Iron Age,” mediating the lost past of a former Heroic Age. Along a similar vein, the Táin has been studied for its mythological resonances and reflexes, though in different directions: either to learn more about the gods and traditions of the Celts (e.g., what more ancient goddess might the Morrígan reflect?) or to consider, often comparatively, the way mythological elements might inform the story itself (e.g., how does Cú Chulainn’s heroic biography culminate in the tale?). Paralleling trends in early Irish scholarship in general, the Táin would eventually come to be read as a literary text, most relevant for its connections to the cultural and social institutions of its medieval audience. Of these strands, much attention has been given to Medb and Cú Chulainn, as well as to the Táin’s attitude toward warfare. While the Táin certainly seems, as Tomás Ó Cathasaigh argues, to celebrate Cú Chulainn as an epic hero with requisite courage, prowess, and loyalty, it also highlights the negative effects of war, as Joan Radner has explained. The clearest example of this juxtaposition comes during the single combat between Cú Chulainn and Fer Diad, his foster-brother. The two men fight for four days, using weapons that bring them closer and closer to one another until Cú Chulainn is forced to use his gae bolga (a special barbed projectile) to rip Fer Diad apart from the inside. Rather than reveling in the victory over his closest equal, Cú Chulainn is distraught and keens over him—questioning the heroic ethos that governs the tale. Medb, the queen of Connacht, is also a complex figure in this regard, as her actions frequently precipitate moments in which various social institutions are critiqued. She instigates the raid and continuously drives it forward—leading sorties, ignoring the advice of her counsellors, cuckolding her husband, and pitting foster-brother against foster-brother. While her agency, which has been connected to a possible origin as a sovereignty goddess, makes Medb unique, it is also undercut throughout the text by misogynistic criticisms, culminating in a scene (in Recension 2) where she is debilitated by her menstruation during the final battle and must yield to Cú Chulainn. One final topic of note is the influence of classical epic on the Táin. This debate has been contentious, but the most recent consensus, led by Brent Miles, is that the Táin as it exists in literary form was likely influenced, in some capacity, by classical works.

Joey McMullen

Indiana University, Bloomington

Works Cited

Miles, Brent. Heroic Saga and Classical Epic in Medieval Ireland. Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer, 2011.

Ó Cathasaigh, Tomás. “Mythology in Táin Bó Cúailnge.” In: Studien zur Táin Bó Cúailnge, ed. Hildegard L. C. Tristram. Tübingen: Gunter Narr Verlag, 1993. 114–132.

Radner, Joan N. “‘Fury destroys the world’: Historical Strategy in Ireland’s Ulster Epic.” Mankind Quarterly 23.1 (1982): 41–60.

Resources

Editions:

O’Rahilly, Cecile, (ed.). Táin Bó Cúailnge: Recension 1. Dublin: DIAS, 1976.

O’Rahilly, Cecile, (ed.). Táin Bó Cúalnge from the Book of Leinster. Dublin: DIAS, 1967.

Translation:

Kinsella, Thomas (trans.). The Táin. London: Oxford University Press, 1969.

Selected Criticism:

Dooley, Ann. Playing the Hero: Reading the Irish Saga Táin Bó Cúailnge. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2006.

Mallory, James P. (ed.). Aspects of the Táin. Belfast: December, 1992.

Miles, Brent. Heroic Saga and Classical Epic in Medieval Ireland. Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer, 2011.

Ó Cathasaigh, Tomás. “Mythology in Táin Bó Cúailnge.” In: Studien zur Táin Bó Cúailnge, ed. Hildegard L. C. Tristram. Tübingen: Gunter Narr Verlag, 1993. 114–132.

Radner, Joan N. “‘Fury destroys the world’: Historical Strategy in Ireland’s Ulster Epic.” Mankind Quarterly 23.1 (1982): 41–60.

Bibliographical resources supplied by Joey McMullen (Indiana University, Bloomington).

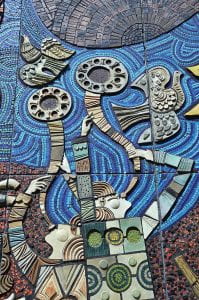

Tàin Bò Cùailnge Mosaic Mural by Desmond Kinney

Images of the Tàin by Louis Le Brocquy, Irish Museum of Modern Art.

Ailbhe Ní Bhriain.. “‘Le Livre d’Artiste’: Louis Le Brocquy and The Tàin (1969).” New Hibernia Review / Iris Éireannach Nua 5.1 (Spring, 2001), pp. 68-82. Journal article that includes illustrations of the Tàin.

Modern adaptations:

An Tàin, graphic novel adaptation by Colmán Ó Raghallaigh, illustrated by Barry Reynolds:

The Cattle Raid of Cooley, webcomic by Patrick Brown. August 12, 2019.

Performance of the Tàin Bò Cùalinge by Alan Irvine, 2016 First Niagara Rochester Fringe Festival

“The Bull.” Fabulous Beast Dance Theater (adaptation)