India

Date of composition: ca. 500 BCE -500 CE

Oldest extant manuscripts: 6th century CE; 11th century CE

Valmiki

Ramayana

The Ramayana was composed in Sanskrit some time between 500 BCE and 500 CE and is attributed to the sage Valmiki. Over the centuries, as the story has been re-told in almost all Indian languages, its characters have been divinized and are now accepted not only as gods and goddesses, but as paradigms for human behavior.

The Ramayana and all its versions and retellings have been at the heart of Hindu culture for more than two thousand years – in literature, performance, painting and sculpture. In fact, the Ramayana provides the metaphors through which Indians understand themselves, an alternative language which explores how we choose to live in the world.

An indigenous tradition of interpretation and explanation, of developing the nuances and meanings of the Ramayana through reflection, commentary and opposition is as old as the text itself. It is these refractions and reflections that seep into the popular imagination and into popular culture – Valmiki’s Ramayana, however, remains somewhat shrouded, seen and understood through the lenses and veils of those who are intimate with the Sanskrit epic.

Through these multiple re-tellings, it is the central idea of dharma (the Hindu code of conduct also defined as the ‘right’ and the ‘good’) that is explored and worked out since there is no categorical imperative for human morality. Many of these retellings (in all the media mentioned) have been prompted by those aspects of the text that have made the tradition uncomfortable, for example, the times when Rama, the hero (who is later acknowledged as an incarnation of the great god Vishnu), acts unrighteously and appears to violate dharma which each individual needs to work out for him/herself.

The story of the Ramayana, a story of trial and tribulation, of the subtlety of right and wrong, love and loss, runs as follows: Rama is the beloved eldest son of a good and wise king, the heir apparent. Sadly, his step-mother Kaikeyi intervenes to make her son king and have Rama exiled into the forest for fourteen years. Rama obeys his step-mother, renounces the kingdom and retreats into the forest with his wife Sita and his devoted younger brother Laksmana. As they travel deeper and deeper into the woods, Rama visits the settlements of many sages and their companions even as he encounters and defeats terrifying demons. One such demon, Ravana, the mightiest of them all, abducts Sita, leaving Rama bereft and grieving but determined to recover his wife and defeat the creature who has now become his sworn enemy. Rama sets up an alliance with a monkey king who commands millions and millions of gigantic monkey warriors to help him defeat the demon. After Sita has been located, a massive battle ensues. The demon is defeated but Rama asks his wife to undergo a public trial by fire to prove her chastity since she had been kept by another man for such a long time. Sita is vindicated and Rama and she return triumphantly to the kingdom which Rama’s noble brother had kept in custody for him.

There is no happy ending, however, as Rama’s inner demons continue to haunt him. The schism between his private and public self, between the loving husband and the king who must be above reproach, is painfully pried open again when Rama is confronted with the citizens’ gossip about his wife’s time in captivity – had she remained chaste in her time away from her husband? Rama chooses to be the public man, the righteous king, and banishes his pregnant wife for the queen cannot be under suspicion. The Ramayana tradition has remained vital and vibrant for precisely this reason: that we continue to debate the righteousness of Rama’s actions and that we continue to seek answers that are meaningful to us, in our time and space, for what this man, exemplar of a culture, chose to do.

Arshia Sattar

Resources

Translation of the complete Critical Edition of the Sanskrit Text:

The Ramayana of Valmiki: An Epic of Ancient India (7 vols.)

Translated and with Introductions and Notes by Goldman, Sutherland, Pollock, et.al.

US Edition: Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ; Indian Edition: Motilal Banarsidass, New Delhi, India.

Abridged Translations of the Critical Edition of the Sanskrit Text:

The Ramayana of Valmiki

Translated and with an Introduction by Arshia Sattar.

US Edition: Rowman and Littlefield, Denver, CO; Indian Edition: Harper-Collins India, New Delhi.

Uttara: The Book of Answers

Translated and with an Introduction by Arshia Sattar

US Edition: Rowman and Littlefield, Denver, CO; Indian Edition: Harper-Collins India, New Delhi.

Abridged Retellings of the Ramayana Story:

The Ramayana for Children by Arshia Sattar

US Edition: Restless Books, New York, NY; Indian Edition: Juggernaut Books, New Delhi

The Ramayana by RK Narayan

Indian Edition: Penguin Classics, Penguin-Random House India, New Delhi; also available in the US.

Contemporary Retellings of the Ramayana Story:

The Forest of Enchantments by Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni

Indian Edition: Harper-Collins India, New Delhi; also available in the US.

The Missing Queen by Samhita Arni

Indian Edition: Zubaan Books, New Delhi; also available in the US.

Critical studies

Ramanujan, AK. “Three Hundred Ramayanas: Five Examples and Three Thoughts on Translation.” In Paula Richman (ed.), Many Ramayanas (see below): 22–48.

Richman, Paula, ed. Many Ramayanas: The Diversity of a Narrative Tradition in South Asia. Berkeley: U of California P, 1991.

The above bibliography was compiled by Arshia Sattar.

Further reading:

Richman, Paula. “Epic and State: Contesting Interpretations of the Ramayana.” Public Culture 7.3 (1995): 631–654.

Richman, Paula, ed. Questioning Ramayanas, A South Asian Tradition. Berkeley: U of California P., 2001.

—. Ramayana Stories in Modern South India: An Anthology. Indiana UP, 2008.

Richman, Paula, and Rustom Bharucha, eds. Performing the Ramayana Tradition: Enactments, Interpretations, and Arguments. Oxford, 2021.

Sattar, Arshia. Maryada: Searching for Dharma in the Ramayan. Harper Collins Publishers India, 2020.

—. Ramayana: Lost Loves: Exploring Rama’s Anguish. Penguin India: 2011, Harper Collins India: 2019.

—. Uttara: The Book of Answers. Penguin India: 2016, Rowman and Littlefield, USA: 2017, Harper Collins India: 2019.

Venu, G. Tolpavakoothu: Shadow Puppets of Kerala. New Delhi: Sangeet Natak Akademi, 2006.

The Ramayana and puppet theater (in the volume World Epics and Puppet Theater):

The Mewar Ramayana (digitized and reunified) can be viewed on the British Library website. The Mewar Ramayana, Roli Books, New Delhi, 2016.

“Sita and Rama: The Ramayana in Indian Painting.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; exhibition of 16 objects.

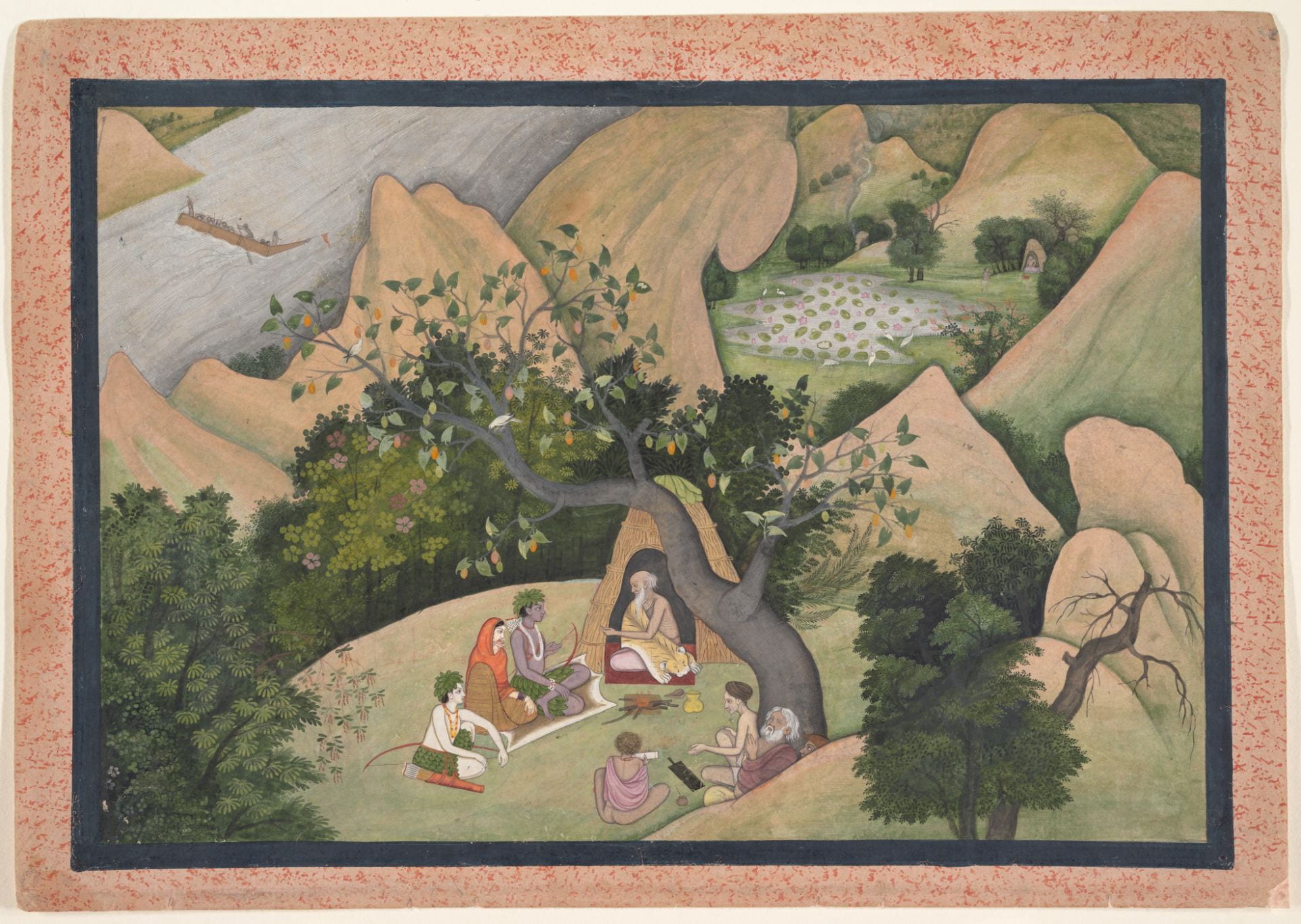

“Rama, Sita, and Lakshmana at the Hermitage of Bharadvaja.” Illustrated folio from a dispersed Ramayana series ca. 1780. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

“Rama and Lakshmana as Boys Assist the Sage Vishvamitra.” Illustrated folio from a dispersed Ramayana series ca. 1780. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

“The Demon Marichi Tries to Dissuade Ravana.” Illustrated folio from a dispersed Ramayana series ca. 1780. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

“Rama and Lakshmana on Mount Pavarasana.” Folio from the Shangri Ramayana series (Style II), ca. 1690–1710. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

“Andhrayaki Ragini.” Folio from a Ragamala series (Garland of Musical Modes); ca. 1710. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

“Rama Releases the Demon Spies Shuka and Sarana.” Folio from the Siege of Lanka series, ca. 1725; attributed to Manaku. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

“Sita in the Garden of Lanka.” From the Ramayana epic of Valmiki, c. 1725; India, Pahari, Guler. The Cleveland Museum of Art.

“Rama, Sita, Lakshmana, and Hanuman Being Worshiped by a Crowd.” Drawing for a Ramayana, attributed to The Kota Master, ca. early 18th century. Harvard Art Museum.

“One of Rama’s sons carried by the monkey hero Hanuman, from the Cambodian or Thai version of the epic of Rama.” Ca. 1950, Asian Art Museum, San Francisco.

“Epic Tales of Ancient India.” Paintings from Edwin Binney 3rd Collection, San Diego Museum of Art (includes art of the Bhagavata Purana, the Ragamala, and the Shahnama in addition to the Ramayana). Full exhibition available on the San Diego Museum of Art app.

Ravanayan comic series, Vivek Goel.

Documentaries

Borrowed Fire: The Shadow Puppets of Kerala:

Documentary by Anurag Wadehra and Salil Singh from 2000 about puppeteers in Kerala, India, who stage episodes from the Ramayana using leather shadow puppets. “Set in a remote village in Kerala, India, this is the true story of the last of the scholar-puppeteers- Krishnankutty Pulavar – and his lifelong struggle to keep alive this ancient art known as Tolpava Koothu (“the play of leather shadow puppets”). Also entwined is the story of the Hindu epic Ramayana that inspires these men to marathon performances year after year.” Explained further in Anurag Wadehra’s blog.

For more on this tradition, see G. Venu, Tolpavakoothu: Shadow Puppets of Kerala. New Delhi: Sangeet Natak Akademi, 2006.

In the Name of God. Directed by Anand Patwardhan, 1992. Hindi with English subtitles.

Tholu Bommalaata: Dance of the Shadow Puppets. June 11, 2020. On the shadow puppetry tradition of performing episodes from the Ramayana and Mahabharata, featuring puppet master Chithambara Rao.

Feature Films

Sita Sings the Blues – animated film written, directed, produced and animated by Nina Paley, 2008. English.

Ramayana: The Legend of Prince Rama (animation). Directed by Yugo Sako, 1992. English.

Raavan. Directed by Mani Rathnam, 2010. Tamil with English subtitles.

Television series

The 78-episode Ramayana tv series (1987-1988) directed by Ramanand Sagar is available on DVD and can also be found on youtube.com with English subtitles.

Puppet theater:

Puppetry Festival in India, organized by the Sangeet Natak Akademi in New Delhi, together with the India International Centre and the Indian Council for Cultural Relations. March 2003. Filmed by Elisabeth den Otter. Excerpts from the Ramayana can be seen at the following moments: Rama catches the golden deer 3:15-4:05; Lakshmana, Rama, and Sita, then Rama and Sita, 4:50-5:45; Ravana, 6:00-6:24; marriage of Sita and Rama, 7:24-8:12; Ravana, 8:58-9:06; the fight between Ravana and Rama, Lakshmana, and Hanuman, 9:25-9:52; Rama kills the golden deer, 9:56-10:55; Ravana abducts Sita, fights with Jatayu, 10:55-11:16; Rama and Lakshmana, Hanuman, Sita receives Rama’s ring from Hanuman, Ravana fights a monkey, 11:23-12:51; Sita, 13:39-14:30; Hamuman, 14:30-14:55.

Katkatha Puppet Arts Trust, About Ram. Trailer. An experimental theatrical piece with excerpts from the Ramayana and narrated by animation, projected images, dance, masks and puppets. Hanuman helps Ram reach Sita who is held captive by Ravan in Lanka. Directed by Anurupa Roy. Animation by Vishal Dhar. Performed by Katkatha Puppet Theatre Group. “About Ram, Anurupa Roy and Puppeteering,” review by Anindita Sengupta. Paula Richman interviews Anurupa Roy (in the volume World Epics and Puppet Theater): Tradition and Innovation in the Making of “About Ram”: A Contemporary Indian Puppeteer and a Ramayana Scholar in Conversation (https://doi.org/10.54103/2724-3346/22210)

Ramayana puppet performances by the Sangeet Natak Akademi in New Delhi, presented by the Ministry of Culture, Government of India. DAY 2; DAY 3; DAY 4; Ramayana. [no subtitles]

Michael Meschke’s Ramayana (1984)

excerpt from the great epos by Valmiki, retold by William Buck

Adaption and translation: Michael Meschke

Music: from the classical Thai repertory

Technique: dancers, musicians, actors and mixed puppet technique

Direction: Michael Meschke

Stage design and puppets after the mural paintings at the Wat Prah Kaew temple in Bangkok.

International company: consisting of Michael Meschke as narrator and puppeteers Francois Boulay, Greta Bruggeman, Monika Meschke-Barth and Silvie Osman, mime artist Tony Sasivanji- Forsman, Michaela Meschke and Somporn Fourrage as well as Thai dancers and musicians from Bangkok and Stockholm.

Guest performances: 1984 in Bangkok(opening performance), Tokyo, Nagoya, Sapporo, Dresden (XIV UNIMA Congress) and Paris; 1985 in Athens

Michael Meschke web page

Additional performances:

Akshara Theater’s Ramayana, based on version by Gopal Sharman. 1) Press and highlights; 2) Hanuman Unmanifest, March 25, 2018.

Kanchana Sita, Saketham, and Lankalakshmi; award-winning trilogy based on the Ramayana by Malayalam playwright C. N. Sreekantan Nair.

Kecak, a Balinese traditional folk dance performance of the story of Ramayana. 1) Uluwatu Temple, Bali (full show); 2) Uluwatu Temple, Bali (partial).

Performances from the International Ramayana Festival 2013. (9 versions- India, Cambodia, Singapore, Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, Philippines, Myanmar, Lao PDR)

Robert Goldman sings from the Ramayana.

“The TV Show that Transformed Hinduism.” Rahul Verma.

Singing:

The following questions are geared toward a discussion of the Ramayana by Valmiki in the context of the upper-level undergraduate course Nobility and Civility: East and West (Columbia University global core).* A syllabus of the course can be found here.

Ramayana (ca. 400 BCE): The Ramayaṇa of Valmiki: an Epic of Ancient India, volume 1, translated by Robert P. Goldman (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984), pp. 1-13, and pp. 41-49; also sargas 1-4, 13, and 17-20. The Ramayaṇa of Valmiki : an Epic of Ancient India, volume 2, translated by Sheldon I. Pollock (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984), sargas 1-28, 57-8, and 90-104 (pp. 79-143, 204-11, and 272-309).

Although we only read brief selections of a work that is extremely long even by epic standards (the television version noted below consists of 78 episodes of nearly an hour each), we should still be able to get a sense of Rama’s defining characteristics. How would you compare him to Gilgamesh or heroes in other epics you’ve read?

Weigh the importance of other factors that led to Rama’s exile beyond the personal motives of Kaikeyi and Manthara.

Note Rama’s reaction to this unexpected news, comparing, for example, “he showed no sign of discomposure” (sarga 16.61) and his characterization as “sorely troubled, heaving sighs like an elephant” (sarga 17.1). Do we know how Rama really feels about being sent into exile by his father just when he was about to take over the kingdom? What is his motivation for accepting this turn of events in his conversations with his brother Laksmana, his mother, and his wife?

The Ramayana also gives sustained attention to female characters, both positive (Sita) and negative (Kaikeyi and especially Manthara). What is at stake in Sita’s disagreement with Rama regarding her desire to accompany him into exile? Note the various reasons she gives in order to persuade him. Why does she ultimately win the argument?

What are the ideas and ideals of statecraft that emerge through the characters’ statements and actions? Pay attention to distinct roles for the brahmin (priestly) class and the kshatriya (warrior/ruling) class. What is meant when Rama tells his brother Laksmana not to act like a kshatriya?

Some of the episodes involve choosing between two courses of action or a conflicting duty (dharma). Is it always clear what is the better option? If so, why do characters sometimes disagree?

Scenes connected to our reading from the Ramayana tv series directed by Ramanand Sagar (1987-1988) can be found on youtube.com.

Jo Ann Cavallo (Columbia University)

*This two-semester course was designed through the Faculty Workshops for a Multi-Cultural Sequence in the Core Curriculum (Heyman Center for the Humanities, 2002-2009), directed by the late Wm. Theodore de Bary, at Columbia University.