Southern India

Oral tradition: c. 15-16th century CE

First recorded: 1965

Ponnivala Nadu

The Legend of Ponnivala Nadu is a folk epic popular in Southern India, specifically in the Kongu Nadu region of Tamilnadu. This is an extended oral epic, a story first tape recorded in 1965, by an anthropologist doing research in the area.

The recording was made during a 38 hour serial performance of the story’s many episodes over 18 nights as it was sung by a well-known local bard, in front of a village audience. A few weeks later the same bard patiently voiced the story over many days allowing a local scribe to write it down. A 1972 publication compares these two versions in depth and is available online (Beck 1972). A full translation of that oral retelling was published in 1992 (Beck 1992). The story’s early history is unknown but it is believed to have reached its modern form in the fifteenth or sixteenth century when many local Tamil legends were first recorded on palm leaves. The first known publication of this epic appeared as a chap book in 1902 and though badly deteriorated it is mentioned in the catalog of the British Museum.

The Ponnivala Nadu legend resembles the Epic of Gilgamesh in several respects and will interest a wide audience for multiple reasons. The story also mirrors the Mahabharata in some ways, particularly in terms of the divine parentage details that surround its key characters. Nonetheless, the story differs greatly from the Mahabharata overall. Although a variety of links to India’s national epic are present, these connections are largely superficial. This local story remains unique and independent in terms of its basic structure and outlook.

The story covers three generations and describes the evolution of one heroic family. Many themes have been woven into this basic fabric, including several perspectives on marital relationships, father-son bonds, brother-brother differences, and the significance of brother-sister ties. The core family in this epic account undergoes many difficult experiences, including an exodus due to drought, a period when they serve as labourers under a powerful king, and then their immigration to a new homeland where the presiding ruler asks them to initiate a new, plough-based farming economy by felling a forest thought to be populated by just a few hunters and craftsmen. Significantly, those early inhabitants resist this encroachment, echoing what is known from other sources about the actual history of this area. At first the story’s heroes are backed by that distant king, but by the time the grandsons inherit their father’s ploughed fields, this hierarchical relationship has become uncomfortable. Eventually the family’s key descendants, a set of male twins, rebel against that distant king and win independence. Notably, the twins embody a long Indo-European tradition that placed a high value on dual-kingship models. This is one of several themes central to this epic that reflect a cluster of much older core concepts.

The Legend of Ponnivala Nadu includes a role for several gods and goddesses whose interventions highlight local beliefs about divine fate, deep concerns surrounding social responsibility, questions attempting to differentiate moral from immoral behaviour, and views featuring a personal sacrifice followed by rebirth. This story is also special for the way in which it bridges Hinduism’s main Vaisnavite-Shaivite divide. Here Shiva and Vishnu are brothers-in-law and their actions balance out. Although these two gods are rivals in this legend, they also cooperate in a variety of ways, making for an interesting, implicit local message from its singers about tolerance and about uniting to face a higher, cosmic challenge.

Furthermore, there are several prominent heroines in this story who lend the epic a key female coloration that one might call its mystic underlay. All of these women enjoy divine connections. Superficially studied, the twin male heroes in the third generation of this story stand out, but if one looks deeper one realizes that the heroes’ sister (a triplet born alongside these two men) proves key to how matters unfold. This sister represents the youngest of the seven bright stars of the Pleiades constellation. Her prominence in the epic is another story thread that appears to have very ancient Indo-European roots. This same thread also marks the story as fundamentally different from India’s famous Mahabharata tradition. This “little sister” appears on earth with a mission: she is there to guide and to constrain her brothers’ raw zeal and ambition. Along with the secret powers of women, this epic also speaks eloquently about the core importance of protecting the basic birth-death cycles, for both humans and animals. In this folk epic all of the lead women remain childless until the gods intervene to help them obtain male offspring. Of course, these divinely “fathered” sons also serve as visible markers of this heroic family’s periodic and miraculous re-infusion with (immaculately delivered) divine semen.

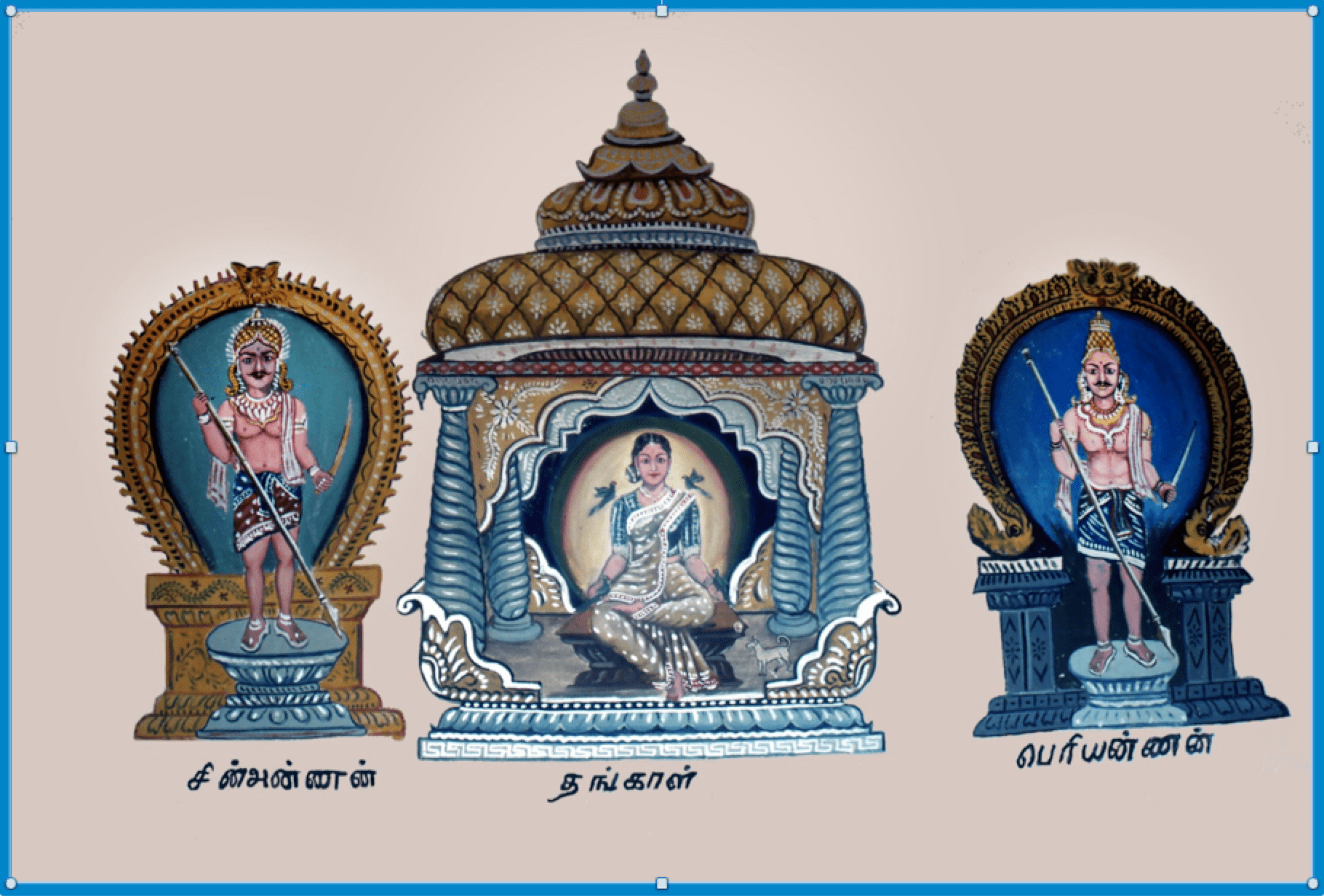

The Legend of Ponnivala story bears links to multiple local shines, most of which honor the story’s heroes and also their fine riding horses (never chariots) using colorful, painted folk statues. The epic’s main protagonists are also celebrated in various folk festivals. In some of these, local story enthusiasts become “possessed” by the heroes’ hovering spirits. Those devotees then “die” by falling down lifeless while reliving a battle their heroes once fought with a group of forest enemies. Late at night the fallen men are then revived by a pre-puberty girl, their magical younger sister. The story is also memorialized in advertising, used in naming local companies and more. It is a great text for teachers and offers a wide variety of topics for study. The story has been animated in a thirteen-hour, serialized video format (Beck 2013; available by contacting the Executive Producer). It also exists as a two-volume, full-color, graphic novel (Beck 2015). It is recommended for courses focused on multicultural understanding and comparative religion, and it illustrates how local bards once constructed a vivid tale that remains popular in rural areas to this day.

Brenda Beck

University of Toronto

Works Cited

Beck, Brenda. 1972. Peasant Society in Konku: A Study of Right and Left Subcastes in South India. Vancouver, University of British Columbia, also translated and now available in Tamil as Konku Kutiyaanavar Camuukam, Adaiyaalam Press, Tiruchi, Tamilnadu, 2019.

—. 1992. Elder Brothers Story (Known as the Annanmar Katai in Tamil). Vols. I & II, A folk epic of Tamilnadu in Tamil (with English on facing pages), Institute of Asian Studies, Madras, Tamilnadu (approximately 780 pages in total), collected, translated and edited by B. Beck.

—. 2013 and 2015. The Legend of Ponnivala. A Graphic Novel in Two Volumes (presented in 26 segments, each sub-story being 36 pp. long, told with full color illustrations that use a traditional South Indian folkart style). Further information in the below bibliography.

Resources

Editions:

Elder Brothers Story (Known as the Annanmar Katai in Tamil). Vols. I & II. A folk epic of Tamilnadu in Tamil (with English on facing pages). Contains the full text of the story as dictated by a bard to a scribe. Collected, translated and edited by Brenda Beck. Institute of Asian Studies, Madras, Tamilnadu, c1990. Approximately 780 pages in total.

English-language publications relevant to the Legend of Ponnivala Nadu story:

Beck, Brenda E. F. 1974. “The Kin Nucleus in Tamil Folklore.” In Kinship and History in South Asia. Ed. Thomas Trautmann. Ann Arbor, University of Michigan Center for South and Southeast Asian Studies. 1-27.

—. 1978. “The Personality of a King: Prerogatives and Dilemmas of Kingship as portrayed in a Contemporary Epic from South India.” In Kingship And Authority in South Asia, Ed. John Richards. Madison, University of Wisconsin, Madison Publication Series, No. 3. 169-191.

—. 1978. “The Hero in a Contemporary Local Tamil Epic.” Journal of Indian Folkoristics. Vol. 1, No. 1, 26-39.

—. 1978. “The Logical Appropriation of Kingship as a Political Metaphor: An Epic at the Civilizational and Regional Levels (India).” Anthropologica. Vol. 20, Nos. 1 & 2, pp. 47-64.

—. 1980. “The Role of Women in a Tamil Folk Epic.” Canadian Folklore Canadien. Vol. 2, Nos. 1&2, pp. 7-29.

—. 1982. The Three Twins: The Telling of a South Indian Folk Epic, Bloomington, Indiana University Press, 248 pp. Now available as a download (due to an ACLS re-publication project).

—. 1982. “Indian Minstrels As Sociologists: Political Strategies Depicted in a Local Epic.” Contributions to Indian Sociology, Vol. 16, No. 1, 35-57.

—. 1983. “Fate, Karma and Cursing in a Local Epic Milieu.” In Karma: An Anthropological Inquiry. Eds. Charles F. Keyes and E. Valentine Daniels. Berkeley: University of California Press. 63-81.

—. 1986. “Social Dyads in Indian Folktales: An Overview.”In Another Harmony: New Approaches to Indian Folklore. Eds. Stuart Blackburn and A.K. Ramanujan. 76-102.

—. 1989. “Core Triangles in the Folk Epics of India.” In Oral Epics of India. Eds. S.H. Blackburn, P.J. Claus, J.B. Flueckiger and S.S. Wadley. Berkeley: University of California Press. 155-175 and 203-207.

—. 2003. “Annanmar Katai.” In South Asian Folklore: An Encyclopedia. Eds. Peter Claus, Sarah Diamond and Margaret Mills. New York: Routledge,. 19-20.

—. 2011. “Discovering A Story.” In Hinduism in Practice, Ed. Hillary Rodrigues. Oxon. U.K.: Routledge. 10-23.

—. 2013 & 2015. The Legend of Ponnivala. A Graphic Novel in Two Volumes (presented in 26 segments, each sub-story being 36 pp. long, told with full color illustrations that use a traditional South Indian folkart style. Order in Tamil or English. Available from N.I.A. Educational Institutions Pollachi, Tamilnadu, India. First published in 2013 via Create Space and available as a print-on-demand purchase at Amazon.com. Each of the 26 segments is also available separately, on Amazon, in Tamil and in English. Some of these materials can be partially viewed on line at http://www.ponnivala.com. A different selection is available at http://www.sophiahilton.ca.

—. 2014. “What The Sister Knew: A South Indian Folk Epic from the Sister’s Point of View.” In Religious Studies and Theology, Vol: 33.1, 65-92. This is a special Issue entitled Divine Domesticity, edited by Patricia Dodd, Memorial University, Nfld.

—. 2016. ”A Tamil Oral Folk History: Its Likely Relationship To Inscriptions & Archaeological Findings.” In Medieval Religious Movements and Social Change: A Report of a Project on the Indian Epigraphical Study. Ed. Noboru Karashima. Tokyo, Japan: Toyo Bunko. 87-123.

2016. “Divine Boar to Sacrificial Pig: References to Swine in the Sangam Texts, in Tamil Folk Tradition and in Ancient Astrological Art.” Part 1, Pandanus, 16/1, 29-54 (actually published in 2017).

2016. “Divine Boar to Sacrificial Pig: References to Swine in the Sangam Texts, In Tamil Folk Tradition and in Ancient Astrological Art.” Part 2, Pandanus, 16/2, 17-58 (actually appeared in 2017).

2018. “Becoming A Living Goddess.” The Oxford History of Hinduism. Ed. Mandakranta Bose. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 201-127.

2019. “Resistance vs. Rebellion in a South India Oral Epic: Two Modes of Opposition To An Expansionist, Self-Aggrandizing, Grain-Dependent State.” Asian Ethnography, Vol 78, Number 2, 25-51.

The above bibliography was compiled by Brenda Beck (University of Toronto).

The The Legend of Poṉṉivaḷa Nadu includes some very interesting descriptions of heaven, earth, and the underworld, including many images that can best be appreciated by reading the story in its heavily illustrated graphic novel form (Beck, The Legend of Poṉṉivaḷa) or by watching the animated version (Beck, The Legend of Poṉṉivaḷa Nadu). The heroine’s long pilgrimage route which links earth with Shiva’s Council chambers high above is especially colorful. These images help the reader imagine what locals thought these various levels of space important in the story might look like.

The artist and animator of this epic account grew up in a village near where the story was collected, and his grandfather was one of this story’s traditional bards. By sitting on his grandfather’s knee as he listened to the story as a child, this superb folk artist was able to illustrate it ‘from the heart’ with images he had developed in his own mind as a young boy.

Beck, Brenda. The Legend of Poṉṉivaḷa, 2012. A graphic novel in two volumes, available as a print-on-demand purchase from Amazon.com (search for books under B.E.F. Beck). Also available for free online viewing at https://ark.digital.utsc.utoronto.ca/ark:/61220/utsc1.

—. The Legend of Poṉṉivaḷa Nadu, 2013. A thirteen-hour animated video program (twenty-six separate half hour segments). Available for free online viewing at https://ark.digital.utsc.utoronto.ca/ark:/61220/utsc1.

Some of these materials can be partially viewed on line at http://www.ponnivala.com. A different selection is available at http://www.sophiahilton.ca.

The story is also available in animated form, as a thirteen hour show (composed of 26 half hour segments). This animated version of the story was broadcast in Canada in 2013 via the Asian television network (in English and in Tamil) and in South India (in Tamil) via Thanthi TV in 2014. Contact the author Brenda Beck at brenda@sophiahilton.ca for a pen-drive copy of these video episodes (with two sound tracks, one in Tamil and one in English).

“Through storytelling fellowship, three U of T Scarborough students reimagine an ancient Tamil epic.” By Rebecca Mangra. University of Toronto. January 27, 2022.