Portugal

1934

Francisco Pessoa,

Mensagem

Francisco Pessoa’s Mensagem (1934) is an esoteric national epic simultaneously steeped in reverential homage to the past while paving the way for what it means to compose an epic in the modern era. This duality can be read in the title itself. Mensagem (Portuguese for “The Message”) is a portmanteau of mens agitat molem (trans. “the spirit moves matter”), a quote lifted from Virgil’s Aeneid. And yet the composite result, “the message,” is a prophetic harbinger of things to come.

The epic is comprised of 44 short poems intended to capture the arc of the Portuguese people. Each vignette focuses on a key figure or event in the nation’s mythological, cultural, or political foundation. The poem is divided into three parts:

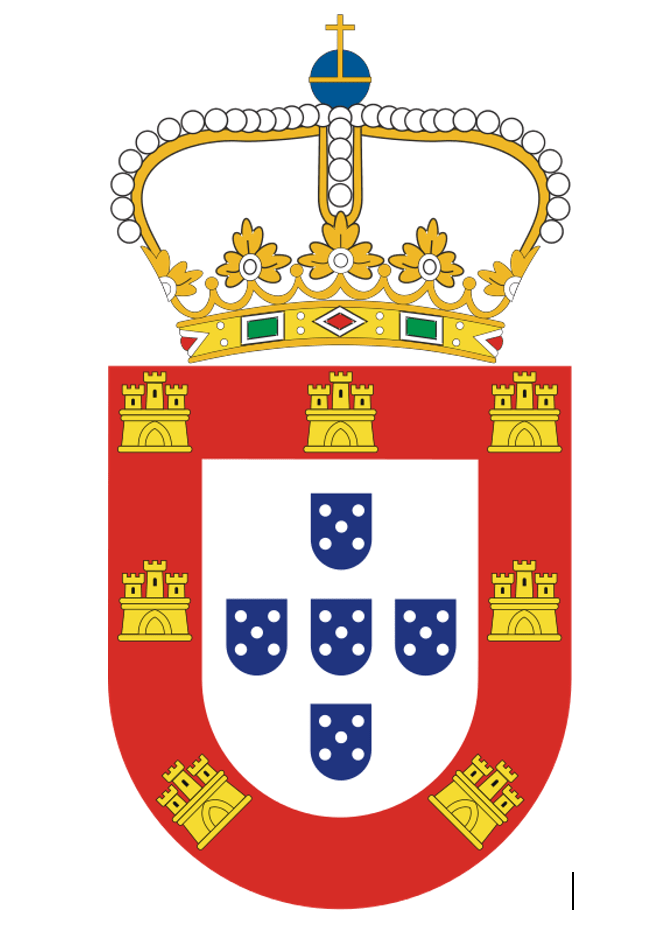

Part I: The Coat of Arms groups poems according to the five major components in the Portuguese coat of arms. Pessoa borrows this framing from Luis de Camões, whose ekphrasis of the coat of arms is one of the most moving passages in the Portuguese epic Os Lusíadas. This section thus immediately positions Mensagem within a broader epic tradition.

Section I: The Fields roots the Portuguese identity in its natural environment. Portugal is cast as a land of liminality. Not quite European and not quite African. Assuredly Mediterranean yet standing on the edge of the ancient world, far afield from the cultural epicenters of Greece, Rome, and Egypt.

Section II: The Castles selects the seven heroes essential to Portugal’s existence. Notably Pessoa again ties Mensagem closely to the pre-existing epic ethos. Ulysses, believed to have founded Lisbon after his return to Ithaca, is centrally placed as Portugal’s founder. Viriathus, a Lusitanian folk hero who liberated the region from Rome, comes next as a figure responsible for national consolidation. Homer’s Odyssey and Brás Garcia de Mascarenhas’ Viriato Trájico thus become required reading to fully understand Pessoa’s work.

Section III: The Shields presents five heroic martyrs whose sacrifices furthered Portugal’s glory. The five shields present on the Portuguese coat of arms are meant to represent the five wounds of Christ upon the cross. In keeping with this symbolism, Pessoa concludes this section with King Sebastian – the messianic Portuguese ruler whose premature death brought the slow collapse of empire.

Section IV: The Crown is left to a singular figure, General Nuno Álvares Pereira. That Pessoa placed his crown atop a general rather than a king firmly injects his own viewpoints into the work. This is his message which is simultaneously Portugal’s message. Crowns may have played an important role in its founding, but Portugal is not bound by them.

Section V: The Crest contains three visionary figures who extended Portugal’s might to the seas, of which Prince Henry the Navigator is the most renowned. This section acts as a mini message, foreshadowing Part II.

Part II: Portuguese Sea contains only one, untitled, section focused on maritime discoveries. Portugal is depicted as having inherited the ancient world and superseded it: “The sea that ends is Greek or Roman, the endless sea is Portuguese.” The Monster, modeled after Camōes’ Adamaster and the closest thing to an antagonist in the poem, is a nondescript barrier to seafaring that must be overcome. It reappears in the penultimate poem (placed in Part III) no longer as an obstacle but finally tamed by Portugal.

Part III: The Hidden One captures the messianic philosophy central to Pessoa’s worldview and makes it impossible to separate the author from his text. Francisco Pessoa was a firm believer in Rosicrucianism – an offspring of Christian mystery cults that hopes to usher in a new age as foretold by the prophet Daniel in the Bible. This last portion of the work embeds Pessoa’s proclamation of the coming age.

Section I: The Symbols presents five visions of national utopia to correspond with the five empires of Daniel’s prophecy. Pessoa yearns for a fifth empire, a Portuguese empire, that can follow in the footsteps of the Greek, Roman, Christian, and European empires that preceded it.

Section II: The Prophesies names the three Portuguese prophets through which the looming fifth age will be revealed: António Gonçalves de Bandarra, António Vieira, and, perhaps unsurprisingly, Francisco Pessoa himself (subject of the only poem in the epic without an individual title).

Section III: The Times acts as the culmination of the work and presents the future in states of being. “Night” turns to “Storm” becomes “Calm” before “Predawn,” an undulating rhythm that announces the fifth age will not come easily. The epic ends with the ominously titled poem “Fog” and the haunting final lines “All uncertain and all is ending / All dispersed and nothing whole / Oh Portugal, today you’re fog… / The Hour has come!”

Mensagem is best read in conversation with Luis de Camões’ Os Lusíadas (1572). In many respects it might be seen as a continuation of it. Camões’ epic heaps praise upon the young King Sebastian as a beacon of Portugal’s resurrection. The waning Portuguese Empire looked to the then 18-year-old ruler to reestablish its place in the world order. Yet, in a cruel twist of life imitating the artistry of the Aeneid’s lament for Marcellus, this was not meant to be. Six years after Camōes’ work was published, the celebrated ruler vanished amidst a disastrous crusade launched against the Kingdom of Morocco and the last gasps of empire slowly departed from Portugal. The enduring message of Os Lusíadas had become obsolete by 1578. Camōes passed away a mere two years after King Sebastian disappeared, distraught that his country faced an increasingly uncertain future. Camões’ message all too quickly dissipated into the ether.

Pessoa corrects what Camões could not. The intervening years between the literary titans produced a millenarian movement, known as Sebastianism, that mythologized the waylaid king. Much like Jesus Christ, Tupac Amaru, or Arthur Pendragon, the firm belief that King Sebastian would one day return began to coalesce in the Portuguese consciousness. This then became Pessoa’s message to tell. Mensagem is an act of millenarian heraldry. Fittingly, the poet himself has become mythologized in turn. Francisco Pessoa is celebrated as a national hero in Portugal. His catalogue of works has become a Portuguese literary gospel while the restaurant in which he wrote Mensagem has become a sort of Mecca.

Mensagem lingers today as a relic befitting its Rosicrucian roots: little known and steeped in mysticism. Yet its importance cannot be overstated. It simultaneously captures the essence of Portuguese identity and the ongoing national identity crisis that emerged following King Sebastian’s disappearance. On a broader level, Mensagem demonstrates what it means to compose a modern epic. Pessoa necessarily built upon the foundation of those epics that came before while using that heritage to proclaim a new message. A prophetic message yearning to be heard.

Columbia University

Pessoa, Francisco. Message. Trans. Martin Earl. Lisbon: Shantarin Editora, 2023.

Resources

English translation:

Pessoa, Francisco. Message. Trans. Martin Earl. Lisbon: Shantarin Editora, 2023.

Further reading:

Feijó, António M. “Fernando Pessoa’s Odd Epic.” In A Revisionary History of Portuguese Literature. Eds. Miguel Tamen and Helena C. Buescu. New York: Routledge, 1999.

Quesado, José Clécio Basílio (2016). “Mensagem, by Pessoa: A Modern Epic.” Modernismo Português, vol. 8, no. 15, pg. 66-71.

The Portuguese coat of arms which inspired the structure of Part I: The Coat of Arms

A special edition of Mensagem sold by A Brasileira