Peru

1596

Pedro de Oña,

Arauco domado

(Tamed Arauco)

Arauco domado (or Tamed Arauco, published in Lima in 1596) is a long epic poem by Pedro de Oña and his first publication at age 26. It includes 19 chants. Oña also wrote two other major poems: Ignacio de Cantabria (about Saint Ignatius), published in Seville in 1639, and Vasauro (The Golden Glass), unpublished until 1941, as well as some minor compositions.

Of all of Oña’s writings, Arauco domado is the poem that offers the richest source and greatest potential for analyzing creole duality and for establishing a dialogue between creole epic poetry and less prestigious genres like the chronicle, legislative discourse, and incipient ethnography. Creoles were the children of Spaniards born in the New World and they started to voice their own perspectives through chronicles and epic poetry in the second half of the sixteenth century.

There are three elements of Arauco domado that expose an inherently paradoxical creole perspective: the first is the direct and proto-anthropological knowledge of Araucanian funerary and religious rituals that Oña presents in Chant 2 of the poem; the second is the exposition of the administrative reforms of the encomienda system (based on landowning and indigenous servitude) that Oña offers in Chant 3; and the third is Oña’s recounting, in Chants 14 and 15, of the creole rebellion in Quito in 1592-1593 against the alcabala or sales tax. Arauco domado thus displays a set of dual perspectives and loyalties that already constituted an early creole agency. However, the poem is also full of classical mythological references and follows models like Virgil, Lucan, and Tasso to illustrate its narration of events.

It is important to note from the beginning that Oña appropriates for himself a specific knowledge about the mores or customs of the natives, a knowledge that differentiates his Arauco domado from the better-known and more canonical poem on this subject: Alonso de Ercilla’s La Araucana (in three parts, 1569, 1578, and 1589). During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, there were two styles of epic poetry in Spain: the verosimilista (or verisimilitude-ist) and the verista (or true-ist). The former followed the orthodox, Aristotelian criterion of exposing universal rather than particular truths (as in the poetry of Bernardo de Balbuena, like El Bernardo, and the treatise Philosophia Antigua Poética by El Pinciano); the latter followed a more realistic or particular approach to the subject of narration even if it did not fall completely in the genre of the rhymed chronicles. Both Ercilla and Oña participated in the two styles, with diverse shades and intensities, especially with regard to the representation of native costumes and rituals, where Oña’s verismo is evident. Even though Oña condemned the idolatrous practices of the Araucanian (or Mapuche) indians, his verismo became the cause of the theological trial he had to undergo in 1596, as soon as his poem was published.

In addition to presenting a “moral” history or history of the natives’ customs in verista style, Oña also offers his views on the reorganization of the encomienda system, the forced taxation by the Spanish state, and the subsequent protests mounted by the Creoles. While expressing a veiled sympathy for some of the protagonists of the rebellion, he nonetheless reaffirms his profound loyalty to the Spanish Crown and the viceregal regime. He even proclaims Viceroy Don García Hurtado de Mendoza as his protector and the supreme hero of his epic poem.

To better understand Oña’s ambiguous position, some historical context is necessary. Don García Hurtado de Mendoza was the second son of Andrés Hurtado de Mendoza, Marquis of Cañete and Viceroy of Peru from 1556 to 1560. In 1557, Don García was sent by his Viceroy father to “pacify” Chile after the Araucanians there had revolted and killed the Spanish governor, Pedro de Valdivia. One of the soldiers in Don García’s four-year expedition to Chile was the young nobleman Alonso de Ercilla, although Ercilla only served for one and a half years, (between 1557 and 1558). Also participating in the expedition was Oña’s own father, Gregorio de Oña, who ended up staying in Chile until his death at the hands of the Araucanians in 1570. That same year Pedro de Oña was born in the remote Chilean town of Angol. Years later, in the early 1590s, Don García Hurtado de Mendoza became Viceroy of Peru, after having inherited the title of Marquis of Cañete upon the death of his older brother. Oña naturally dedicated his Arauco domado to Don García Hurtado de Mendoza. The poem constitutes a heroic version of the 1557 expedition to Chile, sprinkled with long references to events from the 1590s, including the aforementioned tax rebellion in Quito (1592-1593) and the arrival of British corsair Richard Hawkins to Peruvian shores (1594). These two events occupy the last six chants (14 to 19) of Oña’s extensive poem.

Although Oña was born in what is now southern Chile, he spent most of his life in Lima or somewhere else within the borders of contemporary Peru. Because the Kingdom of New Toledo or Capitanía General de Chile was once part of the Viceroyalty of Peru, Oña is claimed by the national literary traditions of both countries. His childhood experience in Araucanian lands would serve him well in the formulation of a possible consciousness for Creoles. This childhood experience is important because it would inform his ambiguous focalizations, his local knowledge, and his dual positioning regarding the decay of the encomienda system and the treatment of Creoles. Although not one of the protesters himself, Oña’s perspective suggests at least some understanding of those who dared speak out against the consolidating ambitions of Spanish metropolitan power. These ambiguous focalizations and their dual positioning reveal an emerging creole sense of ethnic nationhood, a creole-envisioned redefinition of the social pact underlying Spanish rule of the Indies. Creole disagreement over Spanish legislation in the sixteenth century would eventually produce alternative perspectives about social hierarchy and dominion in Spanish America.

José Antonio Mazzotti

Tufts University

Taken from Chapter 1 of The Creole Invention of Peru: Ethnic Nation and Epic Poetry in Colonial Lima (New York: Cambria Press, 2019; an expanded translation by Barbara M. Corbett of Lima fundida: épica y nación criolla en el Perú, Madrid: Iberoamericana, 2016).

Resources

Editions:

Oña, Pedro de (1944 [1596]): Primera Parte del Arauco Domado. Facsímil de un ejemplar enmendado de la primera edición [Lima: Antonio Ri-cardo]. Madrid: Ediciones Cultura Hispánica.

— (1984 [1596]): Arauco domado. A Study and Annotated Edition Based on the Princeps Edition, by Victoria Pehl Smith. Berkeley: PhD dissertation, University of California-Berkeley.

— (2014): Arauco domado. Edizione crítica e studio introduttivo di Ornella Gianesin. Pavia: Ibis.

Critical studies:

Alegría, Fernando (1954): La poesía chilena: orígenes y desarrollo del siglo xvi al xix. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Ángeles Caballero, César (1956): «Los peruanismos en el “Arauco domado”», en Mercurio peruano, no 37, pp. 496-502.

Arellano, Ignacio. “Autoridad y poder en el teatro del Siglo de Oro”, Bulletin hispanique, 119-1 | 2017.

Avalle Arce, Juan Bautista (2000): La épica colonial. Pamplona: Universidad de Navarra.

Castillo Sandoval, Roberto. “¿‘Una misma cosa con la vuestra’?: Ercilla, Pedro de Oña y la apropiación post-colonial de la patria araucana en el Arauco domado.” Revista Iberoamericana, vol. 61, no. 170, 1995, pp. 231–247.

Choi, Imogen. “The Spectacle of Conquest: Epic Conquests on the Seventeenth-Century Spanish Stage.” Epic Performances from the Middle Ages into the Twenty-First Century, edited by Fiona Macintosh et al., Oxford University Press, 2018, pp. 336–350.

Coello, Oscar (2001): Los inicios de la poesía castellana en el Perú: fuentes, estudio crítico y textos. Lima: Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú.

Dinamarca, Salvador (1952): Estudio del Arauco domado de Pedro de Oña. New York: Hispanic Institute.

Dixon, Victor. “Lope De Vega and America: ‘The New World’ and ‘Arauco Tamed.’” Renaissance Studies, vol. 6, no. 3/4, 1992, pp. 249–269. JSTOR.

Iglesias, Augusto (1971): Pedro de Oña. Ensayo de crítica e historia. Santiago de chile: Editorial Andrés Bello.

Marrero-Fente, Rael. “Poesía y astrología en el Arauco Domado (1596) de Pedro De Oña.” Anales de Literatura Chilena. 2016, vol. 26, pp. 117–131.

Massmann, Stefanie. “Épica y Panegírico En Arauco Domado (1596) De Pedro De Oña.” Hipogrifo. Revista de literatura y cultura del siglo de oro, vol. 8, no. 2, 2020, pp. 687–702. [ doi:10.13035/h.2020.08.02.39.

Mazzotti, José Antonio (2004): «El mirador criollo: secretos de la Araucanía y la autoridad del testigo en Pedro de Oña», en Iberoromania Vol. LVIII / no 2, pp. 171-196.

— (2008): «Paradojas de la épica criolla: Pedro de Oña entre la lealtad y el caos», en Paul Firbas (ed.), Épica y colonia: ensayos sobre el género épico en Iberoamérica (siglos xvi y xvii). Lima: Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, pp. 231-262.

— (2016): Lima fundida: épica y nación criolla en el Perú. Madrid/Frankfurt: Iberoamricana/Vervuert, ch. 1, pp. 51-115, “El mirador criollo: Pedro de Oña, entre la lealtad y el caos”.

— (2019): The Creole Invention of Peru: Ethnic Nation and Epic Poetry in Colonial Lima. Amherst, NY: Cambria Press, ch. 1, pp. 51-144, “A Creole Perspective”. This book is an expanded translation of Lima fundida (2016).

Mejías-López, William (1993): “Principios indigenistas de Pedro de Oña presentes en ‘Arauco domado’,” in Quaderni Ibero-Americani, no 73, pp. 77–94.

Pittarello, Elide (1989): “Arauco domado de Pedro de Oña o la vía erótica de la conquista,” Dispositio XIV / 36-38, pp. 247–270.

Porras Barrenechea, Raúl (1952): “Nuevos datos sobre la vida del poeta chileno Pedro de Oña,” Mercurio peruano 33, pp. 524–57.

Raviola Molina, Víctor (1967): “Observaciones sobre el Arauco Domado de Pedro de Oña,” Stylo 5, pp. 71-113.

Rodríguez, Mario (1981): “Un caso de imaginación colonizada: Arauco domado de Pedro de Oña,” Acta literaria 6, pp. 79–91.

Seguel, Gerardo (1940): Pedro de Oña: Su vida y la conducta de su poesía. Santiago de Chile: Ediciones Ercilla.

Vega, Lope de (1856): (1954 [c. 1625]): Arauco domado. Santiago de Chile: Zig Zag. A theatrical interpretation of Pedro de Oña’s epic poem.

Vega, Miguel Ángel (1970): La obra poética de Pedro de Oña. Santiago de Chile: Editorial Orge.

The above bibliography was supplied by José Antonio Mazzotti (Tufts University).

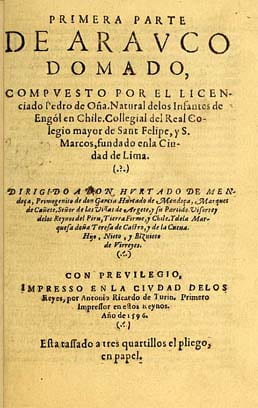

Inside cover of the Arauco domado:

Digital edition of Primera parte de Arauco domado compuesto por el licenciado Pedro de Oña, 1596.

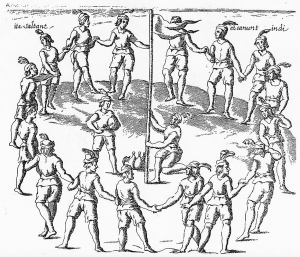

Additional images, memoriachilena, Biblioteca Nacional de Chile.

- “Pedro De Oña: Arauco Domado.” Memoria Chilena, Biblioteca Nacional De Chile, 2018.

- “Arauco Domado, De Pedro De Oña.” Proyecto Estudios Indianos, Universidad Del Pacífico y Universidad De Navarra, 2021.

- Carreño, Dr. Rodrigo Faúndez. “Conferencia: El proyecto de edición crítica del Arauco domado de Pedro De Oña, primera epopeya americana.” Facultad de letras y ciencias humanas, Pontificia Universidad Católica Del Perú, 1 Feb. 2019.

Theatrical trailer from unknown performance of Lope de Vega’s Arauco domado: “Arauco Domado Theatrical Trailer.” YouTube, 12 Sept. 2012.

Unknown author, “Arauco Domado Spot.” Archivo Fílmico UC, 2019. Productora: Escuela de Artes de la Comunicación EAC y Banco de Osorno y La Unión.