Poland

First published: 1834

Adam Mickiewicz,

Pan Tadeusz

(Master Thaddeus)

or

The Last Foray in Lithuania

A Gentry Tale from the years 1811 and 1812

Comprising Twelve Books in Verse

Published in Paris four years after a failed uprising against Russia forced much of Poland’s cultural and political elite into exile, Adam Mickiewicz’s 1834 poem Pan Tadeusz [Master Thaddeus] is considered by Poles to be their national epic—and, arguably, “the only successful epic [the nineteenth century] produced” (Brandes, 284).

The Lithuania of its subtitle, and of its invocation—“Lithuania! My homeland! You are health alone. / Your worth can only ever be known by one / Who’s lost you”—refers to the land of Mickiewicz’s childhood, one of the two historical entities constituting the old Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth that some forty years earlier had been partitioned out of existence by Russia, Prussia, and Austria. The remainder of the subtitle enumerates the key elements of the poem: the climactic event around which the plot is organized as well as the sentiment informing it; the milieu as well as purported time in which it takes place; its length (9721 lines, to be exact); and even, perhaps, a suggestion regarding its genre. Just as significant, though, is the name of its author, Poland’s national poet (1798–1855), whose symbolic autobiography conditions how the poem ought, in part, to be read.

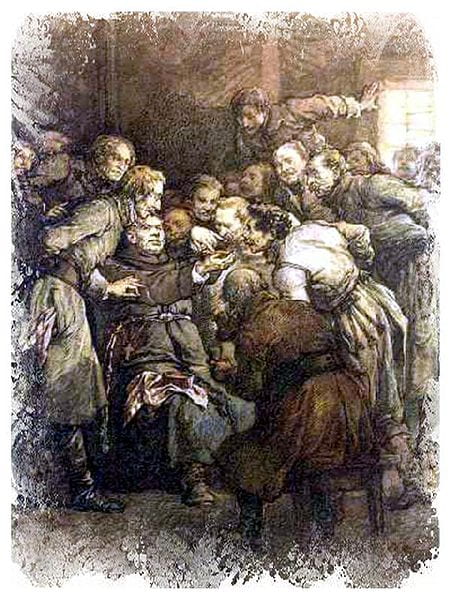

Set in a Polish-Lithuanian backwater of what in 1811 was the Russian Empire, Pan Tadeusz tells the tale of two feuding families, the Soplicas and the Horeszkos, and the budding love between the scion of the former, the eponymous Tadeusz, and Zosia, an orphaned descendant of the latter, who is being raised at the Soplicas’ by a distant relative with her own amorous designs on the young man. The ostensible bone of contention between the two families is a half-ruined castle on the Soplicas’ estate to which the Romantically inclined Count, a distaff Horeszko, decides to lay claim, thanks to the goading of the castle’s Steward and sworn enemy of the Soplicas. Having resolved to take the castle by force, the two call to their aid the neighboring Dobrzyńskis, a fractious gentry clan of very modest means with its own list of grievances against the prosperous Soplicas. As they are staging their foray, a detachment of Russian soldiers arrives to restore order, in response to which the feuding parties join forces to repel a common enemy. This act of armed resistance against the occupying power compels the Polish combatants to flee into exile, where they are nonetheless able to contribute to Poland’s liberation struggle by enlisting in Napoleon’s Polish Legions. The final two books of Pan Tadeusz chronicle the exiles’ triumphant return with the Grande Armée in the spring of 1812, marking the passing of old gentry Poland and its attendant rebirth as a modern nation. The poem concludes with the engagement of Tadeusz and Zosia, at which the guests are treated to a magnificent centerpiece representing the collective’s ethos, a musical retelling of recent Polish history performed on a dulcimer by a Jewish innkeeper, and a toast enjoining those gathered—and reading—to “love one another.”

Like most feuds, the conflict between the Soplicas and the Horeszkos has its origins in a personal drama sometime in the past. Stung by his rejection for the hand of Zosia’s mother, the daughter of the haughty magnate Horeszko, Tadeusz’s father Jacek Soplica, a spirited but impecunious gentryman, had shot the girl’s father just as a Russian garrison was about to storm the latter’s castle, in this way conflating a personal as well as social transgression with (the appearance of) national apostasy. To atone, Jacek donned a monastic habit and assumed the self-abasing name Robak (“worm”). His subsequent engagement as a warrior-monk in the Napoleonic wars, then as a secret emissary who appears in his native Lithuania to prepare the ground for the arrival of Bonaparte’s army, and, finally, his fatal lunge during the foray that shields the Count, the last male of the Horeszko line, from a Russian bullet are all gestures that serve as a template for the collective’s transformation, one founded on sacrifice and thankless toil for the national cause. Jacek’s change of identity marks yet one more in a series of metamorphoses that had come to characterize Mickiewicz’s fictional heroes over the years, each commencing a new chapter in the poet’s symbolic autobiography.

Together with the posthumously published epilogue to the poem, which speaks poignantly of the poet’s sense of émigré dislocation and ache for the land of his childhood, the autobiographical subtext situates Pan Tadeusz squarely in the Romantic nineteenth century. So, too, do the names of Walter Scott and Goethe (as author of the idyll Hermann und Dorothea), which crop up in connection with the early stages of Mickiewicz’s work on the poem. Yet already from its opening thirteen-syllabic line, the traditional meter of Polish epic poetry since the sixteenth century, the poem’s own epic intentions are clear. Pan Tadeusz is a foundational narrative about change and continuity, in which, as one of its early readers put it, “one can not only read [a nation’s] entire soul, but even recognize those everyday features […] that constitute passage from the generation of the dead to the generation of the living, bond it with the future, and bring forth from the grave the nucleus of a future life” (Stanisław Worcell to Mickiewicz, 7 November 1838, Listy, 392–93). And it is precisely Mickiewicz’s capacity to materialize those everyday features, to evoke in a poetic language of remarkable concreteness the colors, smells, and sounds of a provincial, backward world on the verge of extinction, with its bear hunts and tribunals, repasts and vegetable patches, gentry estates and Jewish taverns, petty quarrels and forays, that renders a seamless, “noumenal” tapestry, wherein nature constitutes the woof to society’s warp and where amid humor and pathos there is no room for winter. As yet another early reader of the poem proclaimed, in Pan Tadeusz “the Polish nation will never die” (Julian Ursyn Niemcewicz to Stefan Witwicki, 15 July 1837, Korespondencja, 70).

Roman Koropeckyj

University of California, Los Angeles

Works Cited

Brandes, George. Poland: A Study of the Land, People and Literature. London: William Heinemann, 1903.

Korespondencja Adama Mickiewicza. Edited by Władysław Mickiewicz. Vol. 4. 4th ed. Paris: Księgarnia Luksemburgska, 1885.

Listy do Adama Mickiewicza. Edited by Maria Dernałowicz et al. Vol. 5, Terlecki – Żukowski. Warsaw: Czytelnik, 2014.

Resources

Editions:

Mickiewicz, Adam. Pan Tadeusz, edited by Zbigniew Jerzy Nowak. Vol. 4 of Dzieła. Wydanie Rocznicowe. Warsaw: Czytelnik, 1995.

—. Pan Tadeusz, czyli, Ostatni zajazd na Litwie. Historia szlachecka z roku 1811 i 1812, we dwunastu księgach wierszem, edited by Stanisław Pigoń. Biblioteka Narodowa I, 83. 7th ed. Ossolineum, 1972.

English translations:

Mickiewicz, Adam. Pan Tadeusz. Translated by Kenneth R. Mackenzie. Polish Cultural Foundation, 1986 (with Polish and English Text side by side).

—. Pan Tadeusz: The Last Foray in Lithuania. Translated by Bill Johnston. Archipelago Books, 2018.

Critical studies:

Czaykowski, Bogdan. “Harmony Restored: Mickiewicz’s Pan Tadeusz Reconsidered on the 150th Anniversary of Its Publication. Cross Currents 3 (1984): 181–220.

Davie, Donald. “Pan Tadeusz in English Verse.” In his Slavic Excursions: Essays on Russian and Polish Literature, 43–53. Chicago University Press, 1990.

Koropeckyj, Roman. Adam Mickiewicz: The Life of a Romantic. Cornell University Press, 2008.

—. “Narrative and Social Drama in Adam Mickiewicz’s Pan Tadeusz.” Slavonic and East European Review 76 (1998): 467–83.

—. The Poetics of Revitalization: Adam Mickiewicz between Forefathers’ Eve, Part 3 and Pan Tadeusz. East European Monographs, 2001.

Shallcross, Bożena. “’Wondrous Fire’: Adam Mickiewicz’s Pan Tadeusz and the Romantic Improvisation.” East European Politics and Society 9.3 (1995): 523–33.

Weintraub, Wiktor. The Poetry of Adam Mickiewicz. Mouton, 1954.

Welsh, David. Adam Mickiewicz. Twayne World Authors, 6. Twayne Publishers, 1966.

The above bibliography was compiled by Roman Koropeckyj (University of California, Los Angeles).

Andriolli, Michał. Ilustracje do Pana Tadeusza. Sztuka, 1955.

Pan Tadeusz Museum (Wrocław, Poland).

Culture.pl. “Pan Tadeusz – Adam Mickiewicz.”

Regina Frackowiak. 4 Corners of the World: International Collections. “The Incredible Story of ‘Pan Tadeusz.’”

185th Anniversary of the Publication of Pan Tadeusz Poem (2019)

The above sites were selected by Roman Koropeckyj (University of California, Los Angeles).

Feature Films

Pan Tadeusz. Directed by Ryszard Ordyński, 1928. Silent (no English subtitles).

Pan Tadeusz. Directed by Andrzej Wajda, 1999. Polish with English subtitles.

Performance

Narodowe czytanie Pana Tadeusza [National Reading of Pan Tadeusz]. 1998. (In Polish)

The above selection of performances was compiled by Roman Koropeckyj (University of California, Los Angeles).