Kyrgyzstan

A fragment (in Persian) is dated to the end of the 15th or beginning of the 16th century, but an earlier version may have existed; the first written version of the epic is from the mid-19th century.

Anonymous,

Manas

“…for us, Kirgiz, the dastan remains a precious relic of our far away past, the poetry which is forever near to our hearts.”

Aaly Tokombaiev*

The foundational Kyrgyz epic Manas most commonly refers to a trilogy about Manas, his son Semetey, and his grandson Seytek. Described as the “Iliad of the steppe” (Valikhanov, cited in Reichl, 2016: 330), the first cycle of the epic weaves the history, traditions, customs, and beliefs of a people around the personage of Manas, who unites the forty tribes being attacked and plundered by powerful neighboring tribes and leads his people to the Altai and, eventually, Alai regions. The epic Manas continues to be recited at important events and festivals by bards called “manaschi.” The recording of a recitation of over 500,000 lines by the Kyrgyz master performer Sayaqbay Karalaev makes this epic one of the longest in the world (Jumaturdu, 288).

Manas shares many common themes with other Turkic epics. As seen in the Lines 2110-2120 in Köçümkulkïzï’s translation, the hero is born to a couple who have been waiting a long time for a child. Manas’ birth is precipitated by a feast and their beseeching of God, as well as by a dream (Köçümkulkïzï, Manas, Section I). As the epic progresses, the audience learns that Manas is strong and courageous and has an extraordinary horse that he learns how to ride as a very young child. As a youth, he is mischievous, hard to control, and at the same time very generous. He is accompanied by forty strong men as he defeats his enemies within and outside his tribe. Also similar to other Turkic tales the woman he marries, Kanikei, exhibits great loyalty and strength. Kanikei, who embodies characteristics idealized in Kyrgyz women, is also hospitable, wise, capable, and gentle.

As in other Turkic epics, there is rivalry, corruption, and treachery among the men who vie for leadership of the tribe. In this case, the threats are from Manas’ father and uncles who attack Semetey, Manas’ son, after the hero’s death. Kanikei, as the mother of Semetey, shows that she is capable of great valor and violence if needed to defend and later avenge her son. In contrast to other Turkic epics, Manas includes a tale of friendship between the hero and Almanbet, a Chinese outsider, who is treated as a brother. This bond exemplifies the possibility of friendship with outsiders.

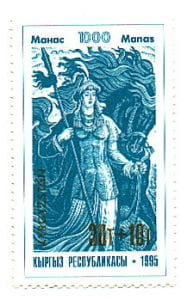

The dating of this epic has caused some controversy and scholarly debates. The earliest written version of the epic is from the mid-19th century and was recorded by Chokan Valikhanov (1835-1865), a Kazakh ethnographer. An older six-line fragment of the epic was found in a historiographical work, written in Persian and dated to the end of the 15th or beginning of the 16th century (Reichl 2016: 329). This does not mean that an earlier version did not exist. A source of great pride for the Kyrgyz, the 1000th anniversary of the Manas epic, was celebrated with great fanfare four years after the declaration of Kyrgyz independence in 1995.

Rather than how old it is, what makes this epic particularly interesting and provides evidence of its importance is how valiantly Kyrgyz and other Central Asian intellectuals, in particular Kazakh intellectuals, fought to promote and defend the epic Manas over the years. In 1925 attempts by Kyrgyz political figures to have it published were refused. While excerpts appeared in newspapers in Moscow in 1946, by the latter years of Stalin’s rule, the Soviet regime labeled Central Asian epics as “obstacles to building socialism” (Benningsen, 464). The Kyrgyz reaction to the attacks on Manas, in contrast to epics from the other Muslim republics, were “bitter, passionate, outspoken,” and came from all layers of Kyrgyz society (Benningsen, p. 468).

In an article based on biographies of the world-renowned Kyrgyz author Chingiz Aitmatov and interviews with his family members, Robinson writes that Aitmatov remembered a tense conference of about 300 scholars at the Kyrgyz Academy of Sciences in Frunze that was forced to convene by party officials. Aitmatov narrated what he saw from the doorway: Mukhtar Auezov, a Kazakh historian and scholar of Manas was listening to speakers one after the other attacking Manas. Then, as recalled by Aitmatov, Auezov stood up and defended Manas, saying: “To take this epic away from the life of its people is like cutting out the tongue of our whole folk” (Robinson, 10). Thirty years later Aitmatov was the chief editor of the first Kyrgyz print edition of a Manas recitation based on recordings made by Auezov (Robinson, 10).

Russian and Turkish translations of Manas, as well as English ones, are available. A section of the epic based on the work of renowned Turcologist Wilhelm Radloff was translated into English by Arthur Hatto in 1977. Walter Mayor published a two-volume translation in 1995 from Russian. Sections have been translated, introduced, and annotated from Kyrgyz by Elmira Köçümkulkïzï and are available online. In 2018 a new English translation of the Epic Manas by Akylay Baimatova based on a Russian edition became available.

There are roughly one hundred recordings by various manaschi from a vast area including Kyrgyzstan, Afghanistan, and Xinjiang, China, of this little-studied epic, which has many elements in common with other Turkic epics that span from Central Asia to Anatolia. One can only hope that more translations will spur greater interest in this literary masterpiece which has inspired films, opera, ballet, libretti, scholarly editions, graphic novels, and works of fiction.

* Cited in Bennigsen, 469. A notable cultural and political figure, Tokombaiev was a national poet, member of the Central Committee of the Kyrgyz Communist party and representative to the Supreme Soviet. The standard transliteration of Kyrgyz has changed over time. I am keeping direct quotes in their original form but otherwise I use the current standard transliteration of Kyrgyz.

Roberta Micallef

Boston University

Works Cited

Bennigsen, Alexandre A. “The Crisis of the Turkic National Epics, 1951-1952: Local Nationalism or Proletarian Internationalism?” Canadian Slavonic Papers 17.2 (1975): 463.

Jumaturdu, Adil. “A Comparative Study of Performers of the Manas Epic.” The Journal of American Folklore 129 No. 513 (Summer 2016): 288-296.

Hatto, Arthur T., ed. and trans. The Memorial Feast for Kokotoy-Khan (Kokotoydun asi): A Kirghiz Epic Poem. London Oriental Series 33. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1977.

Köçümkulkïzï, Elmira. The Kyrgyz Epic Manas. http://www.silkroadfoundation.org/folklore/manas/manasintro.html. Last visited Dec. 31, 2020.

Robinson, Alva. “After Manas, My Kyrgyz, Your Chingiz.” Aramco World (January-February 2019): 6-13.

Reichl, Karl. “Oral epics into the twenty-first century: the case of the Kyrgyz epic Manas.” Journal of American Folklore 129, no. 513 (2016) p. 327+. Gale Academic OneFile, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A460186263/AONE?u=mlin_b_bumml&sid=AONE&xid=439f667f. Accessed 11 Nov. 2020.

Resources

ENGLISH TRANSLATION:

The Memorial Feast for Kökötöy Khan. A Kirghiz Epic Poem in the Manas Tradition. Composed in oral performance by the bard Saghïmbay Orozbaq uulu. Translated by Daniel Prior. Saghïmbay Orozbaq uulu (1867-1930) was a traditional Kirghiz bard who lived long enough to have his extempore performances written down by Soviet folklorists in the early 1920s. Penguin Classics, 2022.

CRITICAL STUDIES:

Bashiri, Iraj. Manas: The Kyrgyz Epic. Bashiri Working Papers on Central Asia and Iran. 1999. https://www.academia.edu/8261597/Manas_The_Kyrgyz_Epic

Başgöz, Ilhan. “The Epic Tradition Among Turkic People.” Heroic Epic and Saga, edited by Felix J. Oinas, Indiana University Press, 1978, pp. 310–35.

Bennigsen, Alexandre A. “The Crisis of the Turkic National Epics, 1951-1952: Local Nationalism or Proletarian Internationalism?” Canadian Slavonic Papers 17.2 (1975): 463.

Chadwick, Nora Kershaw, and Viktor Maksimovič Žirmunskij. Oral Epics of Central Asia. Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Jumaturdu, Adil. “A Comparative Study of Performers of the Manas Epic.” The Journal of American Folklore 129 No. 513 (Summer 2016): 288-296

Hatto, Arthur T., ed. and trans. The Memorial Feast for Kokotoy-Khan (Kokotoydun asi): A Kirghiz Epic Poem. London Oriental Series 33. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1977.

Hatto, A. T., and Robert Auty. Traditions of Heroic and Epic Poetry. Modern Humanities Research Association, 1980. //catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/000245341.

–, ed. and trans. The Manas of Wilhelm Radloff. Asiatische Forschungen 110. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 1990.

Heide, Nienke van der. Spirited Performance: The Manas Epic and Society in Kyrgyzstan. Rozenberg, 2008.

Köçümkulkïzï, Elmira. The Kyrgyz Epic Manas. http://www.silkroadfoundation.org/folklore/manas/manasintro.html. Last visited Dec. 31, 2020.

Laruelle, Marlene. “Kyrgyzstan’s Nationhood: From a Monopoly of Production to a Plural Market”. In Kyrgyzstan beyond “Democracy Island” and “Failing State”: Social and Political Changes in a Post-Soviet Society. Edited by Marlene Laruelle, and Johan Engvall. Lexington Books, 2015 165–84.

Niles, John. “Introduction to the Special Issue: Living Epics of China and Inner Asia.” Journal of American Folklore 129, no. 513 (2016): 253–269.

Prior, Daniel G. “Sparks and Embers of the Kirghiz Epic Tradition In Memoriam Arthur T. Hatto.” Fabula 51, no. 1/2 (2010): 23–37.

Robinson, Alva. “After Manas, My Kyrgyz, Your Chingiz.” Aramco World (January-February 2019): 6-13.

Reichl, Karl. “Oral epics into the twenty-first century: the case of the Kyrgyz epic Manas.” Journal of American Folklore 129, no. 513 (2016) p. 327+. Gale Academic OneFile, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A460186263/AONE?u=mlin_b_bumml&sid=AONE&xid=439f667f. Accessed 11 Nov. 2020.

—. Turkic Oral Epic Poetry: Traditions, Forms, Narrative Structure. New York: Garland, 1992.

—. “Variation and Stability in the Transmission of Manas” (On Formulaic Style in Manas). In Bozkirdan Bagimsizliga Manas [Manas, from the Steppe to Independence]. Edited by Emine Gursoy-Naskali. Ankara: Turk Dil Kurumu, 1995. 32-47.

The above bIbliography of Critical Studies was supplied by Roberta Micallef (Boston University).

IN THE NEWS:

Nienke van der Heide, “Remembering Manas: connected to the past, connected in the present.” International Institute for Asian Studies. THE NEWSLETTER 74 (summer 2016).

Isaeva Asel Keneshbekovna, “Epic of Manas as National Identity,” ICH Courier online. Volume 22.

Paul Salopek, “Weeping, Singing, Roaring – in Rhyme: Kyrgyzstan struggles to revive its tradition of epic bards.” National Geographic. May 2, 2017.

FURTHER READING:

Kamil Maria Wielecki “The Spirit that Permeates the Human Soul: Anthropology, National Epic, and Nation-Building in Kyrgyzstan.” From Facing Challenges of Identification: Investigating Identities of Buryats and Their Neighbor Peoples. Central and Eastern European Online Library 2020: 99-131.

“Kyrgyz epic trilogy: Manas, Semetey, Seytek.” Intangible Cultural Heritage, UNSECO.

Doolot Sydykov’s live 14-hour performance in Ala-Too Square, Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan, November 2020:

(Part 1)

(Part 2)

Kyrgyz Manaschis (traditional storytellers) memorize and perform the entire Manas epic.

Shaabay Azizov:

Karakol, Kyrgyzstan, July 2002 (source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kyrgyz_Manaschi,_Karakol.jpg).

Recorded performance by Shaabay Azizov:

The “Analyzing Kyrgyz Narratives” (AKYN) research group at the American University of Central Asia has made available online six performances of two notable contemporary manaschis. Talantaaly Bakchiev (b. 1971) and Doolot Sydykov (b. 1983) each narrated on three separate occasions, for educational and scholarly purposes, the same episode: the birth of the legendary hero Manas. See the recordings and transcripts

Kyrgyz Epic Storytelling, performance by Turgunaaly Zhusup Mamai (Manaschi).

Performance of an excerpt of Manas by famous Manasachi Shirin Sarygulova, Kyrgyz American Foundation.

Performance of an excerpt of Manas by Ulukbek Toktobolot Uulu, National Geographic.

Links to various performances of the Manas, Music of Central Asia.

Manas recitations, UNESCO.

Premiere of the Manas Opera at Maldybaev Kyrgyz National Academic Opera and Ballet Theater.

“Манас” дастаны/ The Manas epic – YouTube a performance of the epic by various manaschis taking turns. The same Youtube channel (AigineCRC – YouTube) also has recordings of the sequel epics of Semetey and Seytek (albeit without English translation of titles).

“The man who sang the Manas.” Remembering Saparbek Kasmambet, famous performer of epic Kyrgyz poem, the Manas. BBC The Fifth Floor. February 28, 2020.

“Reviving Forgotten Epic Voice.” Janyl Jusupjan, with Daniel Prior. Chaï Latte & Salt podcast.