England

primarily 12th through 15th centuries

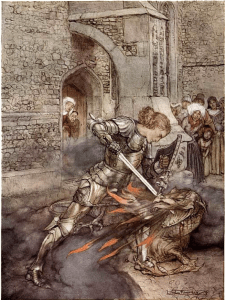

Legends of King Arthur and the knights of the Round Table

The legends of King Arthur and the knights of the Round Table have been the favorites of poets, painters, and politicians for centuries. Perhaps this is because they tap into our deepest ideals of justice, romance, and valor. Or perhaps it is because, although they are fantasy, they do not shy away from asking tough questions: Can love trump duty? Can lofty ideals change human nature? Can we create a legacy that will endure past our own lifetime? Although the Arthurian world is filled with fantastical characters (wizards, sorceresses, and dragons), yet it still presents its protagonists with the harsh realities of life (unrequited love, the painful sacrifices of duty, and doomed romance).

The most famous version of the King Arthur legends is Sir Thomas Malory’s Le Morte D’Arthur, first published in 1485. In his work Malory fused the many previous versions of the Arthurian legends into a complex and sprawling narrative. Le Morte D’Arthur (French for “the death of Arthur”) was a title added by the work’s publisher. This title is an odd choice and a bit misleading because Malory’s work tells about the entire story of King Arthur’s life.

Not much is known about Thomas Malory himself. Malory makes many comments in Le Morte D’Arthur alluding to the fact that he is writing his work while in prison. Records from the time period show that a man named Thomas Malory was charged with various crimes such as burglary, rape (a charge that meant abduction of a female), sheep-stealing, and ambushing a duke. It is still a subject of debate whether or not these charges were legitimate. Malory had powerful enemies who could have easily framed him. Malory’s literary defenders argue that since he is so devoted to the ideals of chivalry in his work, it’s hard to believe that he was a criminal in real life. In a postscript to his work, Malory, calling himself a “knight-prisoner,” asks all the gentle men and women who read his work to pray for his speedy release.

For Europeans, the Arthurian legends are a part of their romantic past. The ideals of the Round Table inspired kings, who tried to form a link between their reign and that of Arthur. Victorian poets such as Tennyson used Arthurian tales of Britain’s past to inspire his country toward a glorious future. Painter-poets such as Rossetti and other Pre-Raphaelites used the stories to feed their yearning for a simpler age. In America, where the legends were re-interpreted with a more democratic slant, Arthur’s humble beginnings and his notions of equality at the Round Table found a new audience. The presidency of John F. Kennedy was frequently compared to the splendors of Camelot. Author T.H. White re-spun Arthur’s life into his novel, The Once and Future King, from which Broadway made Arthur the subject of a popular musical, Camelot.

There is no question that the Arthurian legends have impacted the world, and this led to the inevitable question: Was there a real King Arthur? Many scholars have attempted to identify the historical person who inspired the legends. Their theories culminate in this: If there was a real King Arthur, he lived in Britain during the years following the departure of the Roman Empire and fought against the invading hordes of Saxons. This Arthur, a warlord who fended off barbarian invasion, may have had his “Camelot” at a site now known as Cadbury Castle. (In fact, there are several different proposed locations for the historical Camelot.) As further proof of Arthur’s existence, there is even a tomb at Glastonbury Abbey that claims to be Arthur’s and Guinevere’s final resting place.

As exciting as these historical findings are, they are also bittersweet. No matter how many discoveries are made toward pinpointing this historical Arthur, he is not the Arthur of legends. No real-life person could encompass all that Arthur symbolizes. The legendary King Arthur exists outside time, outside reality, and outside possibility. Yet, rather than limiting his appeal, this merely increases it—especially for students of myth and legend. Arthur and Camelot cannot be found in the real world because they are simply larger-than-life.

The process by which history and myth merged to create the unique feel of the Arthurian legends is too complex to detail here. At their most basic level, the stories are a man’s life—a man who strove for more and achieved much, but maybe not as much as he hoped. We see Arthur’s birth, his youth, his middle years, and finally his death. We see his youthful enthusiasm fade into complacence, and in the end, when he is faced with many enemies, we see that youthful fire reborn. Along the way, Arthur comes to embody something larger than himself. Arthur and Camelot become one, and when one falls, so falls the other.

Arthur’s tale is ultimately a tragedy—a failed experiment—an attempt at something better in the midst of a dark age. Camelot may have ended in failure, but it still inspires us with its legacy. As the lyrics from the musical Camelot say:

Don’t let it be forgot

that once there was a spot

for one brief shining moment

that was known as Camelot.

Zachary Hamby

CreativeEnglishTeacher.com

Work Cited

Malory, Thomas. Le Morte D’Arthur. 2 vols. New York: Penguin Classics, 1970.

Resources

Recommended primary sources

Malory, Thomas. Le Morte D’Arthur Vol. II. New York: Penguin Classics, 1970.

Troyes, Chretien de. Arthurian Romances. New York: Penguin Classics, 1991.

The following questions are geared toward a discussion of Chretien de Troyes’ Knight of the Cart in the context of the upper-level undergraduate course Nobility and Civility: East and West (Columbia University global core).* A syllabus of the course can be found here.

Chretien de Troyes, The Knight of the Cart (c. 1170) in The Complete Romances of Chretien de Troyes, translated by David Staines (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1991), lines 1-931, 1283-2010, 2999-4012, 5300-6107, and 7098-7112.

What kind of ruler is King Arthur? How does he deal with injustice? What concerns are dearest to him? What do his knights think of him?

Is Lancelot a noble hero? If so, how does he demonstrate his nobility? Does Love bring him honor or shame? Consider not only Lancelot’s quest to rescue the queen, but also his actions along the way, such as riding in the cart and jousting to lose. What is his code of conduct and value scale?

What is behind the queen’s anger? Why does it take so much for Lancelot to prove his love and devotion to her? What is his reward?

What is the “political” plot underlying the “romance” plot? You might compare the abduction of Guinevere to that of Sita by Ravana. What are the stakes here beyond the love story?

Note the relations between the two sets of fathers and sons outside Camelot (especially Bademagu and his son Meleagant). Do the opposing positions/characters indicate a generational conflict or a decay in values?

Arthur’s knights may be part of an early medieval literary cycle, but what do you make of the passing reference to the knights who had “taken up the cross to go on a crusade” (p. 240)? What role does religion play in this romance?

How do magic adventures function as tests? (Lancelot sleeping in the bed and defending himself, going into the cemetery and lifting the lid to the tomb, crossing the sword bridge, etc.)

At the outset Chrétien de Troyes states that he writes at the command of his patron Marie de France. Is he thereby showing his unconditional obedience, likening himself to Lancelot? Or, on the contrary, is he ironically distancing himself from the story about to unfold by proclaiming his lack of responsibility for its content?

Jo Ann Cavallo (Columbia University)

*This two-semester course was designed through the Faculty Workshops for a Multi-Cultural Sequence in the Core Curriculum (Heyman Center for the Humanities, 2002-2009), directed by the late Wm. Theodore de Bary, at Columbia University.