Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kazakhstan, Iran, Turkey, Azerbaijan

Transcribed: c. 18th century CE

Anonymous,

The Epic of Köroğlu

Benden selam olsun Bolu Beyi’ne

Çıkıp şu dağlara yaslanmalıdır

Ok vızıltısı, kalkan sesinden

Dağlar seda verip seslenmelidir

Greetings from me to the ruler of Bolu

Who should climb these mountains and lean against them

The mountains should come alive

with the twanging of arrows and the sounds of the shields*

Emerging in the early 17th century, the heyday of brigandage,[1] Köroğlu, the son of the blind man, is one of the most widespread and beloved destan of the Turco-Persian world and neighboring communities.[2] Pertev Naili Boratov (1907-1998), one of the foundational scholars of folklore in Turkey, describes “destan” as the very first literary product of a people. Destans that are about the battles and struggles of heroes, he writes, are reflections of communities and not about individuals.[3] Nevertheless, scholars have found several potential historical prototypes for Köroğlu, suggesting that he might be linked to a historical figure.[4] Even Evliya Çelebi (1611-1682), the well-known Ottoman traveler who was in Anatolia in 1650, mentions a bandit minstrel named Köroğlu in his travelogue.[5]

Variants of Köroğlu are frequently divided into Eastern and Western versions. The Western variants include Anatolian and Caucasian versions whereas the Eastern variants include Turkmen, Kazakh, Uzbek, and Tajik versions. The basic Anatolian tale is the story of a man who is working as an equerry for a notable, frequently the bey of Bolu named in the lines above, but sometimes the Ottoman Sultan or the Shah of Iran. The Bey of Bolu, or the antihero of the epic, asks the equerry to select two fine horses–sometimes for himself and other times to be given as gifts to another ruler or notable figure. The equerry presents two scrawny horses or many horses, two of whom are not particularly attractive but either come from good ancestors or have magical qualities that will appear as they mature. In some variants the horses have been bred by a magician and sired by a sea horse. The Bey of Bolu is insulted when he sees these horses and punishes his equerry by having him blinded. The man leaves with his young son, in many variants named Ruşen or Ali or Ruşen Ali, who now acquires the sobriquet, “son of the blind man.” In many of the Eastern versions, particularly Turkmen and Uzbek narrations, the hero’s name is Guroḡly (son of the grave) because his mother died before giving birth to him and he was born in her grave.[6] In all Western versions Köroğlu vows revenge. His father insists that they wait until the horses mature, or in some variants until they can breed them. In most variants Köroğlu ends up with an extraordinary horse, Kırat, and together they become an invincible team. Either alone or with his father Köroğlu returns for vengeance and establishes a home in “Çamlıbel,” a hill covered in pine trees that overlooks caravan routes. Other men, frequently skilled artisans such as coppersmiths and blacksmiths who have become outlaws because of the unjust government and heavy taxation, join him. The tales also include cycles about love. Frequently the hero falls in love with the sister or daughter of a nobleman, sometimes the Bey of Bolu, or he hears that she has fallen in love with him and he goes to meet her. Then he abducts her and manages to fight off her father and brother as well as their men. The abduction is followed by a magnificent wedding in Köroğlu’s home. In the Anatolian variants he is in love with Nigar and marries her after trials and tribulations. She becomes a much loved, wise mother figure to all those residing in Çamlıbel. In some tales Köroğlu ages and one day simply rides off with his old horse; in other tales he comes across a man with a rifle, declares that rifles destroy bravery, and then rides off into the sunset. In some variants he is a bandit with a heart of gold who, along with his men, steals from the rich and gives to the poor, while in others he is a bard as well as a bandit. In the Western tales Köroğlu is remembered as a brave young man who fights for justice for the poor.

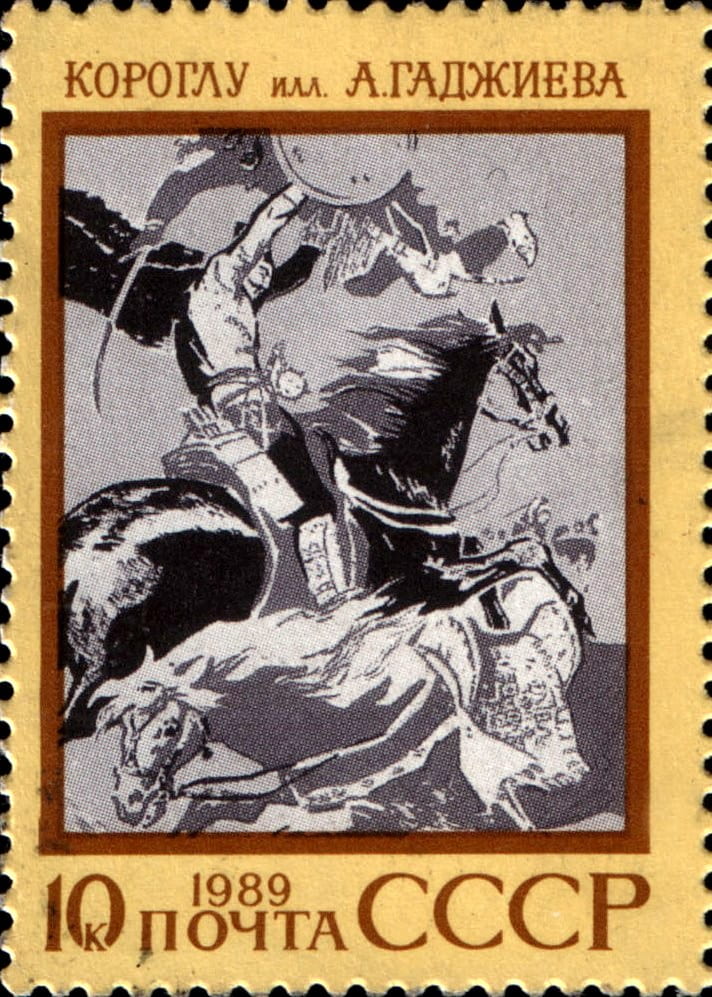

Köroğlu has continued to inspire artists both in the Turco-Persian region and beyond. This destan is very much alive and continues to be updated and narrated by bards across Anatolia, the Caucuses, and Central Asia. It has also been adapted into new forms, including an opera by the Azerbaijani composer Uzeir Hajibekov (1885-1948), films, modern poems, and recordings. A beautiful recording of the epic songs by Ruhi Su (1912-1985), a Turkish folk singer, is available.

Aleksander Chodzko (1804-1891), a Polish orientalist working as a Russian diplomat in Tabriz and Rasht (Iran) between 1832 and 1834, translated and studied the Köroğlu tradition. His Persian/Azeri Turkish manuscript can be found in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France in Paris.[7] Once his research was published in English (1842), it inspired Western adaptations such as George Sand’s (1804-1876) French translation, Les adventures et les improvisations de Kourroglou.[8]

*I translated these lines not literally but rather to evoke the character of the speaker, Köroğlu.

[1] Peirce, Leslie. “Abduction with (Dis)honor: Sovereigns, Brigands, and Heroes in the Ottoman World.” Journal of Early Modern History 15 (2011): 326-27.

[2] Destan has been loosely translated as folk epic, heroic, romantic or both. The stories are a collective reflection on the world and they were narrated often to the accompaniment of a string instrument.

[3]Boratov, Pertev Naili. Köroğlu Destanı. Adam Yayıncılık, 1984. First printed in 1931:14.

[4] Wilks, Judith. “The Persianization of Köroğlu: Banditry and Royalty in Three Versions of the Köroğlu “Destan.” Asian Folklore Studies, 2001, Vol 60, No 2 (2001), pp. 302-318. Wilks provides a nice summary and analysis of three variants of the text as well as a section on the possible prototypes of Köroğlu.

[5] Evliya Çelebi, Seyahatname, Turkish tr. from the Ottoman by Mehmet Zillioǧlu, ed. by Necati Aktaş, 10 vols. in 7, Istanbul, 1973-84. , V:7, 196.

[6] See Wilks for more information about the transformation of Köroğlu in the Eastern variants.

[7] Wilks, pp. 309-310.

[8] Javadi, Hasan. “Köroğlu I. Literary Tradition,” Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition, 2016.

Roberta Micallef

Boston University

Resources

Translations:

Karl Reichl (University of Bonn, Germany) notes that: 1) There is no recent English translation to his knowledge; however, there are sections on this epic cycle in chapters 6 and 10 of his Turkic Oral Epic Poetry of 1992 (reprinted hb. and pb. Routledge, 2018). Chodzko’s translation, still giving a good idea of the epic cycle, is downloadable from the Internet Archive (https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.46223); 2) Monire Akbarpouran recently translated some episodes of an Azerbaijanian version of Köroghlu into French, in Koroğlu du XXIe siècle et les aşıq iraniens (Istanbul: es Éditions Isis, 2021); 3) there is a German translation by Karl Reichl of a branch of the Uzbek Köroghlu/Goroghli cycle, Rawšan. Ein usbekisches mündliches Epos (Asiatische Forschungen, 93. Wiesbaden, 1985) [from January 2022 communication].

The following bibliography was provided by Roberta Micallef (Boston University).

Editions:

Chodźko, Alexander. Specimens of the Popular Poetry of Persia, as Found in the Adventures and Improvisations of Kurroglou, the Bandit-Minstrel of Northern Persia, and in the Songs of the People Inhabiting the Shores of the Caspian Sea, Orally Collected and Translated, with Philological and Historical Notes, London, 1842; repr., New York, 1971.

Critical Studies:

Albayrak, Nurettin. “Köroğlu.” Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı İslam Ansiklopedisi, vol. 26, 2002, pp. 268–70.

Bars, Emin M. “Horse, Women, Weapon In The Epic Of Köroğlu.” Journal of Turkish Studies, vol. Volume 3 Issue 2, no. 3, 2008, pp. 164–78. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.7827/TurkishStudies.293.

Başgöz, İlhan. Hikâye: Turkish Folk Romance as Performance Art. Indiana University Press ; Combined Academic [distributor], 2008.

Başgöz, Ilhan. “Köroǧlu’s Tekgözler (Cyclops) Story.” Wiener Zeitschrift Für Die Kunde Des Morgenlandes, vol. 76, pp. 49–56, JSTOR.

Boratov, Pertev Naili. Köroğlu Destanı. BilgeSu Yayıncılık, 1984, first printed in 1931.

Çelebi, Evliya Seyahatname, Turkish tr. from the Ottoman by Mehmet Zillioǧlu, ed. by Necati Aktaş, 10 vols. in 7, Istanbul, 1973-84.

Chadwick, Nora K., and V. M. Zhirmunskiĭ. Oral Epics of Central Asia. Cambridge U.P, 1969.

Halman, Talat S., Jayne L. Warner. “Köroğlu: Hero in Love.” Popular Turkish Love Lyrics and Folk Legends, ed. Jayne L. Warner, Syracuse University Press, 2009, pp. 49–56, JSTOR. Accessed 2 July 2020.

Hasan Javadi, “Köroğlu I. Literary Tradition,” Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition, 2016. Last accessed on August 22, 2020.

Kurt, Mustafa. “From Epic to Modern Poetry: ‘The Legend of Köroğlu’ by İlhan Berk.” Journal of Turkish Studies, vol. Volume 6 Issue 4, no. 6, 2011, pp. 205–20. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.7827/TurkishStudies.2651.

Letailleur, Erica. “Köroğlu, d’Ali Ihsan Kaleci: Genèse Vivante et Poétique d’une Œuvre Théâtrale En Mouvement.” Carnets, no. Deuxième série-14, Nov. 2018. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.4000/carnets.8569.

Öztürkmen, Arzu. “‘Folklore on Trial: Pertev Naili Boratav and the Denationalization of Turkish Folklore.’” Journal of Folklore Research, vol. 42, no. 2, 2005, pp. 185–216.

Peirce, Leslie. “Abduction with (Dis)honor: Sovereigns, Brigands, and Heroes in the Ottoman World.” Journal of Early Modern History 15, 2011, pp. 311-329.

Reichl, Karl. Singing the Past: Turkic and Medieval Heroic Poetry. Cornell University Press, 2000.

Reichl, Karl. Turkic Oral Epic Poetry: Traditions, Forms, Poetic Structure. Routledge Revivals, 2018. Original published in 1992.

Uluslararası Köroğlu sempozyumu, editor. VI. Uluslararası Köroğlu sempozyumu: “Köroğlu ve Türk dünyası destan kahramanları” bildirileri 10-12 Ekim 2016 : Bolu-Türkiye. BAMER Yayınları, 2016.

Wilks, Judith. “The Persianization of Köroğlu: Banditry and Royalty in Three Versions of the Köroğlu “Destan.” Asian Folklore Studies, 2001, Vol 60, No 2 (2001), 302-318.

Koroglu Overture from Azeri Opera

Benden Selam Olsun Bolu Beyine – Female bard

TRT AVAZ – Children’s Show Koroglu

Koroglu – Kazakhstan Instrumental

The above selection of videos was provided by Roberta Micallef, Boston University.