Finland

Published: 1835; 1849

Elias Lönnrot,

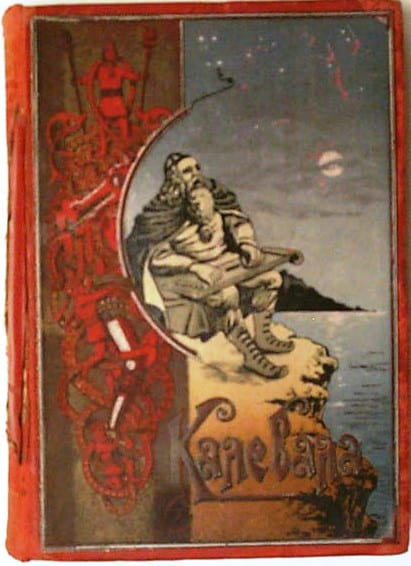

Kalevala

Termed a “tradition-oriented epic,” the Kalevala is a multi-episodic narrative poem created out of folk songs sung by rural Karelian and Finnish singers of the nineteenth century. Incorporating narrative, lyric, and ritual songs, all possessing the same poetic meter (trochaic tetrameter) and many shared stylistic devices (including alliteration and line pair parallelism), the Kalevala was fashioned by an idealistic and industrious district physician and Romantic nationalist Elias Lönnrot (1802-84) in five successive versions completed between 1833 and 1862. In its lengthiest rendition, the so-called “New Kalevala” of 1849, the poem contains 22,795 lines, arranged in 50 cantos.

While reflecting the nineteenth-century folk culture of the regions of Finland and Karelia in which its source songs were collected, the published Kalevala is set in an ancient pre-Christian past, where primordial events like the creation of the world and advent of fire occurred, and where mythic heroes made their lives amid the lakes and forests of a world imbued with magic. Created to serve as a tool of Finnish national identity, the text continues to be viewed by modern Finns as illustrative of the heroism, diligence, resourcefulness, and humor of the Finnish nation.

The title Kalevala translates literally to “the home of Kaleva,” a mythical giant known from Finnish legends, but who plays no part in the epic itself. Lönnrot’s full title for his epic—Kalevala taikka vanhoja Karjalan runoja Suomen kansan muinoisista ajoista [Kalevala or old Karelian poems from the ancient times of the Finnish nation]—acknowledges the dual cultural ties of Lönnrot’s project. On the one hand, it states clearly that the songs are “Karelian”—referring to an agrarian people residing both in the eastern districts of the Finnish Grand Duchy and across the Russian border in what is today the Karelian republic of the Russian federation. On the other hand, the title asserts that the songs stem from the ancient times of “Suomen kansa,” i.e., the Finnish nation, making them components of a Romantic nationalist project to recover and celebrate a heroic past for a Finland that had been for some seven centuries a province of Sweden and then had become, in 1809, an autonomous Grand Duchy of the Russian Empire. Finnish and Karelian languages are closely related and belong to the Finno-Ugric language family, which is distinct from the majority language and culture of both Sweden and Russia. With its stirring tales and powerful lyric imagery, the Kalevala sought to provide the people of Finland (as well European intellectuals) with an answer to questions about the cultural past of the Finnish people and a window into their distinctive and valuable culture.

The source materials for the Kalevala consist of tens of thousands of recorded lines of folk song notated by Elias Lönnrot and other Finnish collectors during the nineteenth century, most of which survive today in the massive folklore archives of Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura (the Finnish Literature Society), a scholarly organization founded in 1831 to facilitate Lönnrot’s work. The preservation, eventual publication, and now thorough digitization of these original notations as Suomen Kansan Vanhat Runot (The Ancient Poems of the Finnish People) make it possible for scholars to compare Lönnrot’s source materials with the rendering of events and characters presented in the Kalevala, a comparison that reveals Lönnrot’s fidelity to his source materials in many respects, but also his shaping of the epic according to his own aesthetic sense.

Mythic and narrative songs employed in the cantos of the Kalevala are dominated by male and female characters that Lönnrot adapted from the song tradition. These include a powerful but aging worker of magic Väinömöinen, an industrious but broody smith Ilmarinen, a hot-tempered and amorous adventurer Lemminkäinen and his wife Kyyllikki, an impetuous aspiring sage Joukahainen and his fated sister Aino, a frustrated and violent orphan Kullervo, a crafty and magic-wielding farmwife Louhi, as well as Louhi’s highly marriageable (unnamed) daughter, whose hand in marriage is sought variously by Väinämöinen, Ilmarinen, and Lemminkäinen, and who is ultimately killed through the actions of a vengeful Kullervo. A further key element of the epic’s narrative involves a mysterious, potent device known as the Sampo, which becomes an object of contention between the male heroes of the land of Kalevala and the forces of Pohjola (the North), headed by Louhi. Characters’ mothers—alive and dead—play important roles throughout the epic as consolers, advisors, and sometimes saviors. Lyric songs are included in the Kalevala to delineate the feelings of various characters and reflect on the situations they face. Ritual songs—songs sung or recited during ritual procedures—are interspersed throughout the epic, drawn from a rich tradition of such works collected by Lönnrot and other fieldworkers in the nineteenth century. These include songs of lamentation and advice that provide guidance to the bride and groom during the traditional Karelian wedding, and incantations (Finnish loitsut) recited when undertaking important actions, including farming, livestock husbandry, hunting and fishing, food preparation, building, and handicraft.

Although constructed on the basis of sung or recited materials, the Kalevala as published reproduces only the lexical content of its sources with none of their aural components. Composers and musical performers have sought to set the cantos of the Kalevala to music in various ways, sometimes drawing on surviving sound recordings of traditional singers from the late nineteenth or early twentieth centuries, sometimes employing symphonic, operatic, choral, or even heavy metal models to give the lines new musical settings. Similarly, visual artists have sought to bring the characters of the Kalevala to life through paintings as well as cinematic and television adaptations.

Thomas A. DuBois

University of Wisconsin–Madison

Resources

Editions

Lönnrot, Elias. Kalevala. Revised edition, Helsinki, Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, 1849. .

Hämäläinen, Niina, Marika Luhtala, Juhana Saarelainen, and Venla Sykäri, editors. Avoin Kalevala. Kansalliseepoksen digitaalinen, kriittinen editio. Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, 2021.

Source Poetry Editions

The Kalevala Heritage: Archive Recordings of Ancient Finnish Songs. Online Catalogue no. ODE8492.

Kuusi, Matti, et al., editors. Finnish Folk Poetry: Epic. Helsinki: Finnish Literature Society, 1977.

Suomen Kansan Vanhat Runot [Ancient Poems of the Finnish People]. Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden toimituksia. Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, 1908-.

Translations

Lönnrot, Elias. The Kalevala: An Epic Poem after Oral Tradition. Translated by Keith Bosley, Oxford UP, 1989.

Lönnrot, Elias. The Old Kalevala and Certain Antecedents. Translated by Francis Peabody Magoun, Jr. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1969.

Selected Criticism

Doesburg, Charlotte. The Adaptation of the Kalevala and Folk Poetry in Finnish Metal Music. PhD dissertation, University College London, 2022.

DuBois, Thomas A. Finnish Folk Poetry and the Kalevala. Garland, 1995.

_____. “From Maria to Marjatta: The Transformation of an Oral Poem in Elias Lönnrot’s Kalevala.” Oral Tradition, vol. 8, no. 2, 1993, pp. 247-88.

Hämäläinen, Niinä. “Why Is Aino not Described as a Black Maiden? Reflections on the Textual Presentations by Elias Lönnrot in the Kalevala and the Kanteletar” Journal of Finnish Studies 18, no. 1, 2014, pp. 91-129.

Honko, Lauri. “The Kalevala: The Processual View” in Religion, Myth, and Folklore in the World’s Epics: The Kalevala and Its Predecessors, ed. Lauri Honko. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 1990, pp. 181-229.

Kallioniemi, Kari, and Kimo Kärki. “The Kalevala, Popular Music, and National Culture.” Journal of Finnish Studies, vol. 13, no. 2, 1992, pp. 61-72.

Laine, Kimmo, and Hannu Salmi. “From Sampo to The Age of Iron: Cinematic interpretations of the Kalevala.” Journal of Finnish Studies, vol. 13, no. 2, 1992, pp. 73-84.

Pentikäinen, Juha. Kalevala Mythology. Translated by Ritva Poom, Indiana UP, 1989.

Ramnarine, Tina K. Ilmatar’s Inspirations: Nationalism, Globalization and the Changing Soundscapes of Finnish Folk Music. U of Chicago P, 2003.

Sawin, Patricia. “Lönnrot’s Brainchildren: The Representation of Women in Finland’s Kalevala.” Journal of Folklore Research, vol. 25, no. 3, 1988, pp. 187-217.

Tarkka, Lotte. Songs of the Border People:Genre, Reflexivity, and Performance in Karelian Oral Poetry. FF Communications 305. Helsinki: Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia, 2013.

Wahlroos, Tuija. “Devoted to the Kalevala: Perspectives on Akseli Gallen-Kallela’s Kalevala Art.” Journal of Finnish Studies, vol. 13, no. 2, 1992, pp. 28-37.

The above bibliography was supplied by Thomas A. DuBois (University of Wisconsin–Madison).