England

c. 1185

Hue de Rotelande,

Ipomedon

Ipomedon is an Anglo-Norman poem written sometime in the last decades of the 12th century (1185?), taking the title from the name of its protagonist hero. Ipomedon, as the name of a Medieval knight, sounds strangely Greek. In fact, all the characters’ names in the poem are taken from the Roman de Thèbes, a Medieval re-elaboration of Statius’ Thebaid. Written in French, the poem is among the earliest examples of roman courtois, contemporary to Chrétien de Troyes’ early poems. It appears in a cultural context familiar with the romans antiques, the Tristan saga, Arthurian myths, and even troubadour notions, recently introduced by Aliénor d’Aquitaine, the wife of Henri II Plantagenet.

We know the name of the author, Hue de Rotelande (probably Rhuddlan in Wales), only because he mentions himself in the poem. Nothing else is known of him except that he lived in Herefordshire and wrote a second poem, titled Protheselaus, as a sequel to the Ipomedon (the hero is the son of Ipomedon). Protheselaus is dedicated to Gilbert de Monmouth Fitz Baderon, nobleman of the Anglo-Norman kingdom.

The story

Prologue

Ipomedon is the young son of the king of Puglia (Southern Italy). Having heard certain knights singing the praises of the Duchess of Calabria (a vassal of her own uncle, the king of Sicily), Ipomedon decides to spend some time at the court of Calabria. The young Duchess is named la Fière because she has vowed not to marry anyone unless he were the most valiant knight in the world. When she realizes that Ipomedon is in love with her, she rebukes him in spite of her own feelings of tenderness toward him. Ipomedon leaves the court, determined to have his own chivalric valor recognized.

The Three-Day Tournament.

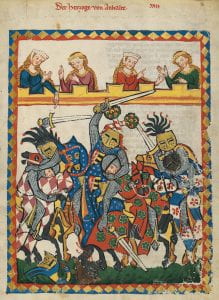

The barons of Calabria insist for the Duchess to get married. It is agreed that she will marry the winner of a three-day tournament, and the announcement goes around so that knights from all over Europe and the Mediterranean region may participate. Ipomedon takes part in the tournament, dressed each day in armour of a different colour: white the first day, red the second, and black the third. He emerges the winner but, not yet satisfied, intends to further pursue his search for recognition and departs from the region, leaving the Fière in wait.

The War in France

In France the king Atreus is involved in a bitter war with his brother Darius. Ipomedon offers his services to the king, defeats Darius, and reconciles the two brothers. On his way back to Italy he is informed that la Fière is being besieged by an unwanted, dreadful suitor, an ugly half-giant from India maggiore.

The fight against Leonin

Ipomedon confronts Leonin in a long and difficult fight, and eventually defeats him. Against all expectations, however, he goes in front of the walls of la Fière’s town, speaks as if he were Leonin and invites la Fière to get ready to follow him to India. La Fière then orders a fleet to sail from the town.

Epilogue

In the meantime, though, another knight of the king of Sicily, by the name of Capaneus, has heard of the predicament of La Fière and hurries to rescue her. He intercepts Ipomedon, assuming he is Leonin, and confronts him. Tired and wounded from the fight against Leonin, Ipomedon loses strength and Capaneus seems to be gaining the upper hand. One of his strikes removes the part of armour that covers Ipomedon’s hand, and he notices a ring which Ipomedon had received from his mother. This discovery reveals that Ipomedon is Capaneus’ half brother, and the two now reconcile and go to the court of la Fière where the lovers are finally reunited. Ipomedon returns to Puglia where he is crowned king and marries la Fière and where the couple will “live happily ever after”.

If one tries to relate this poem to works of the Anglo-Norman cultural context from which Hue may have derived the motifs forming the plot, some of the links to romans antiques, the Tristan saga, Arthurian myth, and troubadour culture are rather obvious while others remain uncertain. The three-day tournament is a prominent motif that reappears in the anonymous Partonopeus, Chrétien’s Cligès and Le Chevalier de la Charrete, and in the German poem Lanzelet, re-elaboration of a lost Anglo-Norman work, as well as in the later Italian cantare of Bel Gherardino. Several critical studies notwithstanding, the connections among these poems is still sub judice, in part because the exact date of composition of Ipomedon as well as that of related poems is still controversial.

The most noticeable aspect of this poem is, in my opinion, the fact that the reader is constantly made aware of a situation in which the narrator entertains a group of listeners. The narrating voice keeps commenting the story he tells, with sentences destined to give credibility to the twists and turns of the story, “common sense” statements on the “qualities” of women, and allusions to contemporary events and characters. He develops, moreover, a “complicity” with his listeners every time the characters in the story are duped by Ipomedon’s disguises. It is perhaps on account of his entertainment abilities that now and then Hue disregards certain discrepancies and contradictions that appear in the poem’s plot.

The poem reveals a prominent humorous attitude: the narrator injects in this romantic story ironic, burlesque elements, even to the limits of obscenity. These are more evident in the two narrative segments in which Ipomedon spends time at the court of the king of Sicily: the first time he requires the king’s permission to accompany the queen everyday to and from her chamber and give her a kiss, and is thus called le dru la reine. The queen falls in love with Ipomedon (“cele erbe mut pres de sun flanc / Eüst mut volentieri liee, / De ren ne serreit si hetee,” “she would have so willingly mingled that grass that grows close to her hip [with his], nothing else would have made her so happy”), but he remains faithful to his beloved. The second time, in order not to be recognized, Ipomedon disguises himself as a fool, raising the hilarity of the king of Sicily’s courtiers, and he follows the damsel that had come to the court of Sicily to ask for help on behalf of la Fière. The damsel, that had at first despised the fool, ends up falling madly in love with him.

In the tradition of the roman courtois genre, dominated by Chrétien de Troyes’ poems, Ipomedon represents an early and quite distinct type of poem. Its fame, which remained alive in England, did not spread as far in Europe as that of Chrétien’s more refined works. Nonetheless, it may at some point have been present in Italy, where the Normans had established a kingdom with its capital in Palermo. I have translated the poem into Italian, partly because I believe that an indirect trace of the poem may be found in the cantare of Bel Gherardino, but mostly because it appears to me a very enjoyable and interesting work, worth of being much more widely known.[1]

[1] Hue de Rotelande, Ipomedon (poema del XII secolo). Translation into Italian and introduction by Maria Bendinelli Predelli. Florence: Società Editrice Fiorentina, 2021.

Maria Bendinelli Predelli

McGill University