New Spain (New Mexico)

First published: 1610

Gaspar Pérez de Villagrá

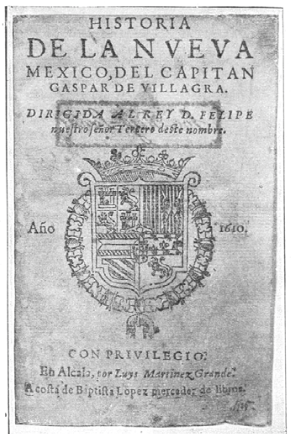

Historia de la Nueva México

When Gaspar Perez de Villagrá began writing his Historia de la Nueva México (1610), a Spanish epic about Don Juan de Oñate’s colonial expedition through New Mexico, he had a few high-profile models in mind. Velasco’s Eneida (1555)—the first complete Spanish translation of Virgil’s Aeneid—had proved the suitability of Castilian verse for epic, and Ercilla’s La Araucana (1569–89) had established the Spanish conquest of America as a desirable subject for the genre. Both works were extremely popular, going through multiple editions and reprintings over several decades. Villagrá’s poem was partly an attempt to show off his own literary credentials, but it was even more important as a confirmation of epic as an appropriate—perhaps even the ideal—genre through which to view the Spanish imperial campaign.

Like Ercilla, Villagrá had first-hand knowledge of his subject. A creole who had been born in New Spain and educated at the University of Salamanca, Villagrá was one of the chief officers in the 1598–99 expedition. The first half of the Historia focuses on Oñate’s journey from Mexico to New Mexico, while the second half dramatizes the conflict that erupted between Oñate’s army and the natives of Acoma—a battle that ended in 1599 with the complete destruction of the Acoma pueblo and the imprisonment and mutilation of its defeated survivors.

While the Historia centers on these large-scale events, a surprising number of the poem’s thirty-four cantos are devoted to relatively mundane matters. For example, cantos 7 through 9 focus on the mandatory inspection of Oñate’s army by royal officials, an onerous process that devolves into a bureaucratic nightmare because of technical delays created by the Spanish viceroy. Villagrá even goes so far as to include complete transcriptions of the king’s and viceroy’s official letters within the text of the Historia. This attention to the legalese of Spanish imperialism led many twentieth-century critics to characterize the work as chronicle rather than epic poem, sometimes referring to it as the “first published history of New Mexico” (Encinias, Rodríguez, and Sánchez, xviii).

Yet, despite its fixation on imperial bureaucracy, the Historia is first and foremost a literary work. Villagrá loudly proclaims the epic status of his poem in its opening lines, which are directly modelled on the opening of Virgil’s Aeneid:

Las armas y el varón heroico canto,

El ser, valor, prudencia y alto esfuerzo

De aquel cuya paciencia no rendida,

Por un mar de disgustos arrojada,

A pesar de la envidia ponzoñosa

Los hechos y prohezas va encumbrando

De aquellos españoles valerosos

Que en la Occidental India remontados,

Descubriendo del mundo lo que esconde,

‘Puls ultra’ con braveza van diziendo

A fuerza de valor y brazos fuertes,

En armas y quebrantos tan sufridos

Quanto de tosca pluma celebrados.

(1.1-13)

I sing of arms and the heroic man,

The being, courage, care, and high emprise

Of him whose unconquered patience,

Though cast upon a sea of cares,

In spite of envy slanderous,

Is raising to new heights the feats,

The deeds, of those brave Spaniards who

In the far India of the West,

Discovering in the world that which was hid,

‘Plus ultra’ go bravely saying

By force of valor and strong arms,

In war and suffering as experienced

As celebrated now by pen unskilled.

From the outset, Villagrá makes clear that Oñate is a modern-day Aeneas who will advance the Spanish cause and continue the westward translation of empire. Even more than Virgil’s Aeneas, who is occasionally prone to fits of passion, Oñate is a paragon of self-control and piety in the first half of the Historia. He repeatedly shields his soldiers from the messiness of colonial politics, instead taking upon himself both the financial and psychological costs of the campaign’s many setbacks. He also proves more than once that he is favored by God. In one episode, Oñate discovers an indigenous town plagued by drought, and he responds by having his men publicly pray to God for rain. A rainstorm soon follows, bringing “so much water on all that land / That the barbarians were amazed” (Por toda aquella tierra tantas aguas / Que espantados los bárbaros quedaron, 16.59–60).

Oñate’s stature diminishes greatly in the second half of the poem, however, as the focus moves to the battle of Acoma and its devastating outcome. The historical Oñate was officially accused of tyranny and eventually banished from New Mexico because of his murderous treatment of deserters and indigenous peoples. By contrast, in the Historia the failure of the expedition is indirectly suggested by Oñate’s absence—he disappears from the poem’s action in the last six cantos. Instead, Villagrá foregrounds here the tragic fate of the Acomans, whom he repeatedly represents as a second Troy. When the dying Bempol mourns the destruction of the pueblo, he distinctly echoes Virgil’s lament for the beleaguered Trojans in Book 1 of the Aeneid: “O Acoma, what god have you defied, / What reason is there that the lofty gods / Should wish to be angered at us!” (¡O Acoma, a qué Dios has ofendido / O por qué causa assí los altos dioses / Quieren contra nosotros enojarse!, 33.70–72). Zaldívar, a Spaniard, puts it more bluntly and succinctly: “Here was Troy” (Aquí fue Troia, 33.416).

Many modern readers see Villagrá’s epic fashioning of indigenous Americans as a subtle critique of Spanish imperialism. This may be true, but it may also say something about Villagrá’s belief in the value of classical poetry. Before he was a soldier, Villagrá was a student in Salamanca, and while there he fully grasped the usefulness of humanist learning. Throughout the Historia, he reminds his patron, Philip III, that—in the colonial sphere—the pen is as important as the sword: “It being no less to write of deeds…than to undertake them” (No siendo menos escrivir los hechos…Que emprender nos, 1.37–39) . The poem includes scenes of battle, but it also contains many moments in which Spanish colonists try to communicate with indigenous peoples and read their cultural artefacts. Thus, in representing the expedition through the form of epic, Villagrá suggests to his king (and to his readers) that humanistic skills are precisely those most useful for understanding New World civilizations—and, one can reasonably assume, for controlling them.

Joseph M. Ortiz

University of Texas at El Paso

Works Cited

Encinias, Miguel, Alfred Rodríguez, and Joseph P. Sánchez. “Introduction.” Historia de la Nueva Mexico, 1610, by Gaspar Pérez de Villagrá, University of New Mexico Press, 1992. xviii-xxiv.

Gaspar Pérez de Villagrá. Historia de la Nueva Mexico, 1610. Translated and edited by Miguel Encinias, Alfred Rodríguez, and Joseph P. Sánchez. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1992.

Resources

Edition

Gaspar Pérez de Villagrá. Historia de la Nueva Mexico, 1610. Translated and edited by Miguel Encinias, Alfred Rodríguez, and Joseph P. Sánchez. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1992.

Critical Studies

Davis, Elizabeth B. “De mares y ríos: conciencia transatlántica e imagineria acuática en la Historia de la Nueva México de Gaspar Pérez de Villagrá (1610).” Épica y colonia: Ensayos sobre el género épico en Iberoamérica (siglos XVI y XVII), ed. Paul Firbas. Lima, Peru: Fondo Editorial de la UNMSM, 2008. 263–86.

López-Chávez, Celia. Epics of Empire and Frontier: Alonso de Ercilla and Gaspar de Villagrá as Spanish Colonial Chroniclers. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2016.

Martín-Rodriguez, Manuel M. “History, Poetry, and Politics in Gaspar de Villagrá’s Historia de la Nueva Mexico.” Camino Real: Estudios de las Hispanidades Norteamericanas 4 (2012): 87–100.

Padilla, Genaro M. The Daring Flight of My Pen: Cultural Politics and Gaspar Pêrez de Villagrá’s Historia de la Nueva Mexico, 1610. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2010.

Quint, David. Epic and Empire: Politics and Generic Form from Virgil to Milton. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993.

The above bibliography was supplied by Joseph M. Ortiz (University of Texas at El Paso).