Arabia, Persia, and the Subcontinent

Oral tradition dating back to the 7th century

Illustrated manuscript commissioned by the Mughal Emperor Akbar, c. 1562

Urdu version by Ghalib Lakhnavi, 1855

Expanded by Abdullah Bilgirami, 1871

Ghalib Lakhnavi

The Adventures of Amir Hamza

Hailed as “the Iliad and Odyssey of medieval Persia” (Dalrymple), Dastan-e Amir Hamza (The Story of Amir Hamza) is an ahistorical and areligious narrative built around the life and times of Hamza bin Abdul Muttalib, the uncle of Prophet Muhammad, who lived in Arabia from 566 to 625 C.E. Through centuries of the story’s adaptation into diverse narrative traditions and art forms, especially through the Indo-Persian oral storytelling genre known as dastan, history and fact have been subsumed into the fantastical. The most extensive version, written by various storytellers of the time and first published by the Naval Kishore Press (Lucknow, India) between 1883 and 1917, is an Urdu dastan spread over 46 volumes averaging a little over 915 pages each.

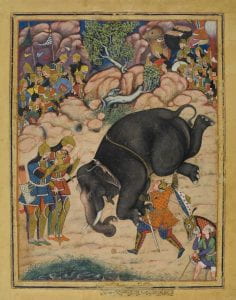

From the Hamzanama, Vol. 11, painting number 47, India, Mughal Dynasty. Attributed to Mahesa and Kesava Dasa (1570). Original Caption: Two brothers lift an elephant on the field and Farrukh-Nizhad goes and lifts an elephant and converts them to Islam (trans. from Seyller Cat. 52). The caption Seyller uses for his catalogue reads: “Lifting an Elephant Single-Handed, Farrukh-Nizhad so Astonishes Two Brothers That They Convert to Islam” (pg. 165). Folio in the MAK, Vienna. Photographic credit: MAK/Georg Mayer. Ownership credit: MAK – Museum of Applied Arts, Vienna. Source: https://www.mak.at/en/program/exhibitions/adventure_with_hamza

The recent Adventures of Amir Hamza-Lord of the Auspicious Planetary Conjunction (2007) is the only complete and unabridged translation of the one-volume Urdu dastan text by Ghalib Lakhnavi and expanded by Abdullah Bilgirami. This version begins by recounting the events before Hamza’s birth and thus serves as a prequel to the stories of most of the dastan’s consequential characters.

Culturally and religiously marginalized for its allegedly low literary value and profanities, the text of the Dastan-Amir Hamza has not been studied with enduring seriousness until recently. The non-availability of translations has also kept it cordoned off from enquiry by a wider audience. Such has been the neglect around the genre of the ‘dastan’ that the word itself has yet to be adequately defined in keeping with its codes and poetics. Anglophone theorists like Francis Pritchett and Pasha Muhammad Khan translate the word and the genre as ‘romance’. While one sees the theoretical benefits to be garnered from this translation, it is nonetheless an Anglophone approximation that does not fully capture the complexities of an indigenous genre.

Unlike the written text, the visual representations based on the story have enjoyed international renown. The miniature painting folios of the Hamzanama from 1562-1577 were the magnum opus of Mughal Emperor Jalaluddin Muhammad Akbar’s atelier. Of the original 1400 illustrations, only 126 have survived. These were acquired by the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, and The Mak, Vienna, in the early twentieth century. The folios have since been printed in John Seyller and Wheeler M. Thackston’s The Adventures of Hamza: Painting and Storytelling in Mughal India (2002).

The first historical references to stories venerating Hamza date back to the time of the Prophet following Hamza’s martyrdom in the Battle of Uhud (625 C.E.): after commissioning the killing of Hamza, the enraged Hinda chews his heart and liver in retribution for the slaying of her father Utba in single combat in the Battle of Badr (624 C.E.). The one-volume Dastan-e Amir Hamza refers to this history as a matter of fact with the proviso that “the truth and fiction of this tale be attributed to the inventors of the legend” (Lakhnavi and Bilgirami 906). In the dastan, Hinda hamstrings Hamza’s horse, the three-eyed Ashqar Devzad (born of a dev), kills Hamza herself, and then cuts his body into seventy pieces before chewing up his heart and liver.

The 46-volume version of the story eschews any connection to the historical. This longer cycle – which was first written and developed solely in the Indian Subcontinent (1883-1917) – left the historical figure of Amir Hamza as merely a reference point, a figurehead for the storyteller’s vocation. In fact, in most volumes of the longer cycle of tales, Hamza, the original Sahibqiran (Lord of the Auspicious Planetary Conjunction), no longer makes a physical appearance.

Scholars of Dastan-e Amir Hamza have commonly asserted that there is no need to study the historical or religious linkage between Hamza ibn Abdul Muttalib and the eponymous hero of the dastan. In their respective analyses of the Hamza story, S.R. Faruqi, M.A. Farooqi, D.M. Lang, G.M. Meredith-Owens, Zahra Faridany-Akhavan, William Hanaway, John Seyller, and Frances Pritchett conflate the Hamza of Dastan-e Amir Hamza with other historical personages like Hamza the Kharijite, especially with reference to the story’s earlier Persian context. Given, however, the clear historical identifiers present in the text as well as in the miniature paintings, the dastan’s use of historical fact as a basis for spinning stories is an area open to further investigation.

The stories from the oral narrative tradition follow a general division into four basic types as expounded by Ghalib Lakhnavi in his Preface to the 1855 edition of the one-volume Dastan-e Amir Hamza: razm (warfare), bazm (courtly assembly), tilism (magical enchantment), and ayyari (trickery). The Hamza of the dastan is a follower of the monotheistic “True Faith”, or Deen-e Ibrahimi (The Religion of Abraham), who serves the polytheist, fire-worshipping “Emperor of the Seven Climes”, Naushervan the Just, in Ctesiphon.[1] Hamza conquers vast expanses of land and quells rebellions across India and China not only through the agency of his prowess but also thanks to the divine gift bestowed upon him by Prophet Aadam so that his “arm will never be lowered by [any] adversary, nor will anyone ever prevail against [his] arm’s might” (Lakhnavi and Bilgirami 233). This sets the stage for an enduring conflict between the followers of the “True Faith” and the “fire-worshippers” in Naushervan’s court. The conflict is also fuelled by Hamza’s betrothal to Naushervan’s daughter, the much sought-after Princess Mehr-Nigar. While waiting for an auspicious alignment of the heavenly bodies for the nuptials, Hamza moves to the Land of Qaf –– a realm of jinns, peris, and devs –– to help Emperor Shahpal bring the mighty jinn back under his rule. The eighteen-day journey turns into an eighteen-year separation from Mehr-Nigar who is protected throughout these years by Hamza’s trusted aide, confidant, and milk-brother, Amar Ayyar, the master trickster. While in Qaf, Hamza marries Aasman Peri, who gives birth to a half human, half jinn daughter, Quraisha. Many battles and tilisms later, Hamza returns to earth aided by the mythical Simurgh and by the Prophets Khizr and Ilyas. The one-volume Dastan-e Amir Hamza ends with Amir Hamza’s martyrdom while fighting for the forces of the “True Faith” under Prophet Muhammad at Uhud.

Please see the Summary tab in the Resources section below for a more detailed plot summary.

[1] Seven Climes stands for the seven regions of the earth. Ctesiphon (Mada’in) is the collective name of the seven cities that flourished during Naushervan’s reign.

Mariam Zia

Lahore School of Economics, Pakistan

Works Cited

Dalrymple, William. “Eat Your Heart Out, Homer.” New York Times Book Review. Jan. 6, 2008.

Lakhnavi, Ghalib and Abdullah Bilgirami. The Adventures of Amir Hamza. Complete and Unabridged. 1871. Translated from Urdu by Musharraf Ali Farooqi. Modern Library Classics. Random House, 2007.

Lakhnavi, Navab Mirza Aman Ali Khan Bahadur Ghalib. Tarjuma-e Dastan-e Sahibqiran Giti-sitan Aal-e Paighambar-e Aakhiruz Zaman Amir Hamza bin Abdul-Muttalib bin Hashim bin Abdul Munaf (A Translation of the Adventures of the Lord of the Auspicious Planetary Conjunction, the World Conqueror, Uncle of the Last Prophet of the Times, Amir Hamza Son of Abdul Muttalib Son of Hashim Son of Abdul Munaf). 1855. Introduction by Rafaqat Ali Shahid. Karachi: Oxford University Press, 2013.

Resources

TEXTS (ENGLISH TRANSLATIONS):

Jah, Muhammad Hussain. Hoshruba: The Land and the Tilism. 1883. Translation from Urdu by Musharraf Ali Farooqi. Random House India, 2012.

Lakhnavi, Ghalib and Abdullah Bilgirami. The Adventures of Amir Hamza. Complete and Unabridged. 1871. Translated from Urdu, with an introduction and notes, by Musharraf Ali Farooqi. Modern Library Classics. Random House, 2007. Special abridged edition, 2012.

Pritchett, Frances W. The Romance Tradition In Urdu: Adventures From The Dastan Of Amir Hamzah. Columbia University Press, 1991.

Seyller, John William, and Wheeler M. Thackston, eds. The Adventures of Hamza: Painting and Storytelling in Mughal India. Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, 2002.

CRITICAL ESSAYS AND THESES:

Faridany-Akhavan, Zahra. “The Problems of the Mughal Manuscript of the Hamzanama”: 1562-1577. A Reconstruction”. PhD Diss. Harvard University. 1989.

Farooqi, Musharraf Ali. “Dastan-e Amir Hamza Sahibqiran: Preface to the Translation.” Annual of Urdu Studies 15 (2000): 169-173.

—. “The Simurgh-Feather Guide To The Poetics Of Dastan-E Amir Hamza Sahibqiran.” Annual of Urdu Studies 15 (2000): 119-167.

Hanaway, William. “Persian Popular Romances Before the Safavid Era”. PhD Diss. Columbia University. 1970.

Khan, Pasha Mohammad. The Broken Spell: Indian Storytelling and the Romance Genre in Persian and Urdu. Wayne State University Press, 2019.

Lang, D. M., and G. Meredith Owens. “Amiran-Darejaniani A Georgian Romance and its English Rendering.” Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 22.03 (1959): 454-490.

Shirazi, Quratulain and Ghulam Sarwar Yousof. “Historical and Cultural Relevance of The Adventures of Amir Hamza.” International Journal of English and Literature 4.6 (2013): 259-263.

Shirazi, Quratulain. “Sahibqirani: An Ideal of Kingship and Manhood in the Romance of Amir Hamza.” The Journal of Religion and Popular Culture 26.2 (2014): 187-201.

Zia, Mariam. “Religious Orientations, Storytelling and the Uncanny: A Reading of The Adventures of Amir Hamza.” PhD. Diss. University of Sussex. 2017.

INFLUENCE ON LATER AUTHORS:

Anonymous, “Dastan-e.Amir.Hamza and Salman Rushdie’s Two Years, Eight Months and Twenty-Eight.Nights.” South Asian Review 2020. DOI: 10.1080/02759527.2020.1851518. To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/02759527.2020.1851518

CRITICAL STUDY (URDU)

Faruqi, Shamsur Rahman. Sahiri, Shahi, Sahibqirani: Dastan-e Amir Hamza ka Muta’lea (Magic, Kingship and Lordship of the Auspicious Planetary Conjunction: A Study of The Adventures of Amir Hamza). 5 vol. 1999. Qaumi Council Barai Taraqee-e Urdu Zuban, New Delhi: 1999, 2006, 2006, 2011, 2012.

The above bibliography was compiled by Mariam Zia (Lahore School of Economics, Pakistan).

IN THE NEWS:

William Dalrymple, “Eat Your Heart Out, Homer,” NY Times book review (January 6, 2008).

Ghalib Lakhnavi and FIRST CHAPTER “The Adventures of Amir Hamza.” NY Times article (

“Menak Amir Hamza, the Javanese version of the Hamzanama,” British Library, September 28, 2018.

“The ‘Odyssey’ of Mughal India,” Qantara.de.

ENCYCLOPEDIA ENTRY:

Entry on the Hamzanama in the Encyclopedia Iranica.

The collection of Hamza-Nama images at the MAK, Vienna.

Hamzanama. Folios in the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Indonesian wayang puppet of Amir Hamza (Wong Agung Jayeng Rana).

List of folios of the Hamzanama, the British Museum.

Hamzanama. Folios of at the Smithsonian National Museum of Asian Art.

Watercolor of the Hamzanama, Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Watercolor of the Hamzanama. The Brooklyn Museum.

List of folios of the Hamzanama, the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Slideshow of folios, Google Arts & Culture from MAK Museum of Applied Arts.

See also:

Culin, Stewart. “ILLUSTRATIONS OF THE ROMANCE of AMIR HAMZAH.” The Brooklyn Museum Quarterly, OCTOBER, 1924, Vol. 11, No. 4 (OCTOBER, 1924), pp. 139-143. Published by: Brooklyn Museum. JSTOR.

The Adventures of Amir Hamza. Francis Pritchett’s website. Includes texts and resources for the one-volume Dastan-e Amir Hamza as well as for the 46-volume cycle of the Hamza stories.

The HOSHRUBA Project. Musharraf Ali Farooqi’s website.

Dastangoi performance, by Mahmood Farooqui, UC Berkeley.

For the circulation of these narratives as part of Indonesian wayang (traditional puppetry/drama) in Java and Sunda (West Java), see Kathy Foley, “Amir Hamzah: Epic of Islamization,” in Puppetry International 50 (Fall and Winter 2021): 20-23.

Episode of “Explore the Orbis” podcast on the Hamzanama.

The narrative begins by expounding the conception of justice in Ctesiphon (present-day Madain, Iraq) under Qubad Kamran, Naushervan’s father, where ironically, one of his viziers kills his teacher and mentor for the Seven Treasures of Shahdad (AAH 6). The teacher is Khvaja Buzurjmehr’s father and the student is Bakhtak’s maternal grandfather. The stage is set for a battle between Buzurjmehr, a follower of the True Faith who forgives the crime against his father, and Bakhtak, the Sassanid who continues to nurse a grudge and swears by the Meccan goddesses al-Lat and Manat and the fire temple of Nimrod. This sets up the religious bifurcation that will endure throughout the narrative.

Naushervan dreams that a jackdaw will come from the East and take his crown away while a hawk from the West will restore it, and hence Buzurjmehr’s calculations predict it will be Hamza who restores Naushervan as the Emperor of the Seven Climes. This creates a linkage between the followers of the True Faith and the “fire-worshippers”, another enduring feature of the dastan. Hamza will always fight for Naushervan, while Naushervan ‘under the guidance of Bakhtak’ will always fight against Hamza (AAH 57-58). Hamza is born to the chief of the Banu Hashim tribe Khvaja Abdul Muttalib at the time of an auspicious planetary conjunction and is hence fated to fight off everyone he considers a foe, whether human or jinn. At the same time, two other boys are born: Amar and Muqbil (AAH 59-66). Amar will be an ayyar (trickster) without peer and Muqbil Vafdar or Muqbil the Faithful will be a matchless archer. A sahibqiran, an ayyar and an archer endowed with divine gifts from various prophets will take on the infidels in the name of the True Faith, while at the same time fighting for an emperor who is an ‘infidel’ (AAH 87-92).

In Naushervan’s court, Hamza falls in love with his daughter Mehr-Nigar and most of his battles are a result of Naushervan wanting to delay the nuptials after being caught between the wish of his bravest commander and loyalty to the Sassanids who want Mehr-Nigar as a bride (AAH 181-198). But from his battles and Divine help, Hamza amasses his own army which includes the best warriors of his times, the likes of Landhoor bin Sadaan, Bahram Gurd and Aadi Madi-Karib (AAH 220-271). Hamza swears he will not marry anyone till he marries Mehr Nigar but ends up marrying Naheed Maryam at the slightest of coaxing by Amar (AAH 325-329). After various attempts on his life, including two attempts to poison him, just when Hamza could have been married to Mehr Nigar he decides to go to Qaf to fight off the devs who have rebelled against Emperor Shahpal (AAH 371-378). Instead of the planned 18 days, Hamza spends 18 years in Qaf fighting off devs and jinn, marrying Shahpal’s daughter, the fairy Aasman Peri, and having his first child, Quraisha, with her, and later finding ways of getting back to Earth after the benevolent devs fearing Aasman Peri’s wrath refuse to help him. It is in Qaf that Hamza arranges the nuptials of a peri and a jinn who later disguised as a horse impregnates the peri and the resultant colt becomes Hamza’s much celebrated three-eyed steed, Ashqar Devzad (AAH 534-578/Seyller 144-145). In the parallel human world, Amar the master trickster moves from one fortress to another protecting Mehr Nigar through his cruel and eschatologically inclined trickery. In the meantime, her father sends various Sassanid commanders one after another to defeat the army of the followers of the True Faith (AAH 451-69 and 662-664).

Hamza finally returns and gets married to Mehr Nigar (AAH 713) and they have a son, Qubad. When Qubad is murdered (AAH 758), a distraught and aggrieved Mehr Nigar is also wounded (759). When she dies, Hamza decides to spend the rest of his days at her grave (760). But he returns to the battlefield and marries various women before he begins his escapades with different tribes including those of cannibals, women and trees. He loses most of his commanders and army and is left with only seventy people when he returns to serve under his nephew, Prophet Muhammad. He is martyred at the battle of Uhud, fighting for the Muslim army when Hinda hamstrings Ashqar, cuts Hamza’s body into seventy pieces and chews up his heart and liver (AAH 904).

by Mariam Zia (Lahore School of Economics, Pakistan)